In a frank and public act of self-examination, a group of doctors at Massachusetts General Hospital published an article Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine detailing the missteps that led to the death of a cancer patient who received a fecal transplant as part of an experimental trial. The man who died, and another who became severely ill, had received fecal matter from a donor whose stool turned out to contain a type of E. coli bacteria that was resistant to multiple antibiotics.

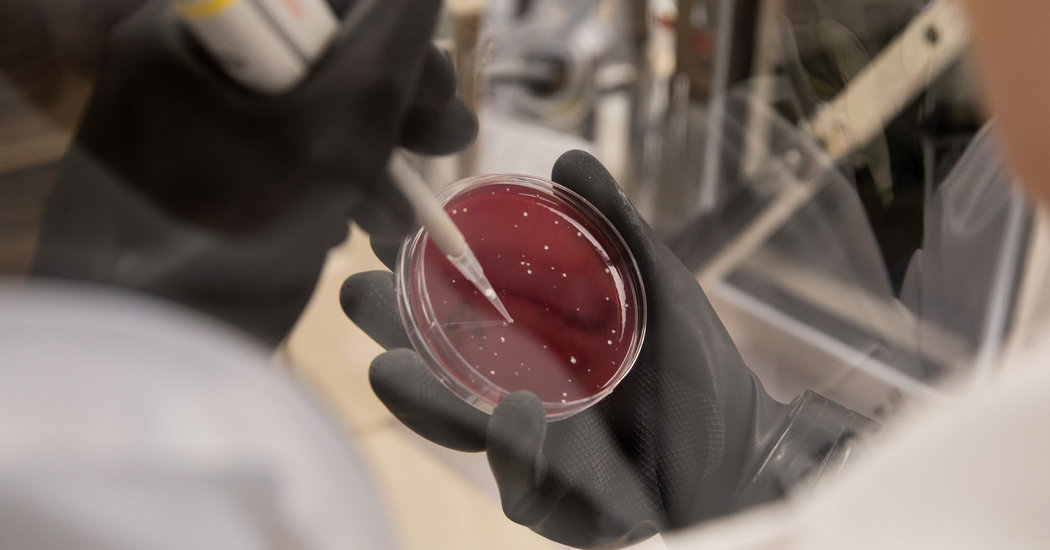

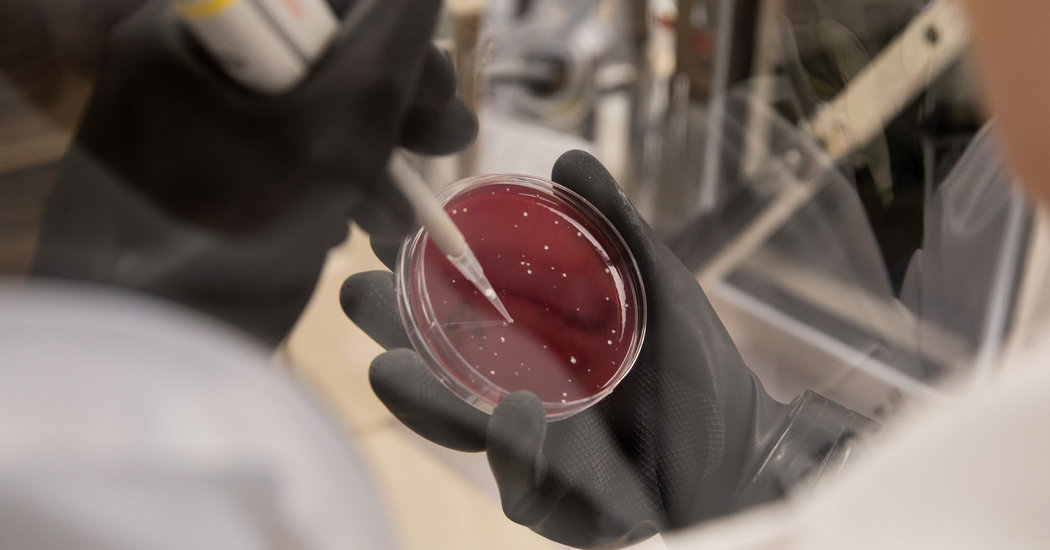

The death shook the emerging field of fecal microbiota transplants, or F.M.T., a revolutionary procedure that transfers feces from healthy donors to the bowels of sick patients in an effort to restore their microbiome, the community of beneficial bacteria and other organisms that dwell in the intestines.

Fecal microbiota transplants remain unapproved by the Food and Drug Administration, but the treatment has proved highly effective in combating a deadly bacterial infection known as Clostridium difficile, which kills thousands of Americans annually. Researchers have also been exploring its use for conditions ranging from Alzheimers to autism.

Dr. Elizabeth L. Hohmann, the lead author of the article and an infectious disease specialist who oversees fecal transplant trials at Mass General, expressed remorse over her lab’s failure to test stool from a donor that had been stored in a freezer for several months.

“It’s been professionally very challenging,” she said in an interview. “But this is a cautionary tale about the risks of cutting edge projects.”

After doctors reported the incidents to the F.D.A., the agency issued a nationwide alert to health care providers and patients about the risks of the procedure and urged researchers to suspend fecal transplants until labs could safely screen for drug-resistant microbes. Many projects have since resumed.

The patients at Mass General fell ill from E. coli bacteria that produced an enzyme called extended-spectrum beta-lactamase, which made the bacteria resistant to multiple antibiotics. The bacteria are often harmless in healthy people but can wreak havoc on those with compromised immune systems.

The New England Journal article provided a detailed, up-close look at how doctors at Mass General administered encapsulated stool from a donor whose feces had been successfully used to treat scores of patients with C. diff, a debilitating bacterial infection that tends to strike hospitalized patients who have been treated with multiple rounds of antibiotics.

Doctors at Mass General had been testing stool donations for a multitude of infectious bugs, following F.D.A. protocols. In January, the agency tightened the screening standards to include a number of emergent organisms like the drug-resistant strain of E. coli.

The problem, Dr. Hohmann said, was that the F.D.A. did not instruct doctors to test or destroy older material kept in storage. “It wasn’t obvious to a lot of smart people here,” she said. “We didn’t think to go back in time.”

The patients sickened by the compromised feces were participating in two separate experimental trials last spring. One patient, a 69-year-old man with end-stage liver disease, received capsules over the course of three weeks. The other, a 73-year-old man with a rare blood cancer, was given the capsules before undergoing a bone marrow transplant. Both men had also been administered antibiotics.

The men turned feverish soon afterward. The liver patient developed pneumonia that tests later determined was caused by the drug-resistant E. coli strain. He was treated with a powerful antibiotic and eventually recovered.

The cancer patient, who had taken drugs to suppress his immune system as part of the bone marrow transplant, declined more precipitously. Eight days after his last F.M.T. dose, he was placed on a ventilator. He died two days later from a severe bloodstream infection.

Genomic sequencing tests later confirmed that the organisms came from the same donor. Looking back at their actions, the doctors acknowledged in the article that the decision to give both men antibiotics before their fecal transplants might have provided an opportunity for the drug-resistant E. coli strain to thrive.

“We’ve been going through a lot of 20-20 hindsight here,” Dr. Hohmann said.

The incident prompted widespread angst among patients and practitioners in the rapidly evolving field of fecal microbiota transplantation.

Dr. Ari Grinspan, a gastroenterologist at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York who helped pioneer fecal transplants for C. diff, said he received a flood of panicked calls and emails from former patients who thought they might have received compromised stool.

“What happened was horrific, but it’s reminded us that we have to be vigilant about screening protocols,” he said.

The cases have also heightened tensions that have pitted doctors who perform fecal transplants against drug companies that are developing new microbiota therapies derived from human stool. Those companies have been pressing the F.D.A. to more tightly regulate the procedure as a new drug, which some doctors and patient advocates fear would give companies proprietary control over the active ingredients in transplanted feces.

The F.D.A. will hold a public hearing next week in Washington to better understand the risks and benefits of the therapy. For now, the agency allows fecal transplants for C. diff patients who have not responded to standard therapies, an approach known as enforcement discretion.

In a statement yesterday, the agency said: “The F.D.A. would like to clarify that the use of FMT to treat C. difficile remains investigational at this time and the efficacy and safety of this intervention have not yet been established.”

Unlike Mass General, which produces its own fecal transplant material, most of the treatments used by doctors in the United States come from OpenBiome, a nonprofit stool bank in Cambridge, Mass., that has provided 50,000 doses in recent years without any reported serious adverse events related to the material, according to Carolyn Edelstein, the executive director.

OpenBiome has been testing donors for the drug-resistant strain of E. coli since 2016, she said, adding that fewer than three percent of prospective donors make it through the rigorous screening.

In an era of mounting antimicrobial resistance, many doctors said the incident underscored the challenges presented by organisms that are constantly evolving in their effort to survive the onslaught of antibiotics used in medicine and agriculture. Dr. Alexander Khoruts, a gastroenterologist at the University of Minnesota, said his lab had also been testing for the E. coli strain, but there is always a fear a newly virulent bug will slip through the screening process.

“This is a potential issue that could even be existential and we need to address it head on and always be ahead of the game,” said Dr. Khoruts.