Companies that make reusable, snakelike cameras to examine patients internally should begin making disposable versions, because the current models cannot be properly sterilized and have spread infections from one patient to another, the Food and Drug Administration said on Thursday.

In the meantime, hospitals that use the instruments, called duodenoscopes, should start to transition to models with disposable components to reduce the risk of infection to patients, the agency said.

Duodenoscopes, which are used in about 500,000 procedures a year in the United States, have been implicated in hospital outbreaks sickening hundreds of patients. Tests ordered by the F.D.A. found that one in 20 harbored disease-causing microbes like E. coli even after being properly cleaned.

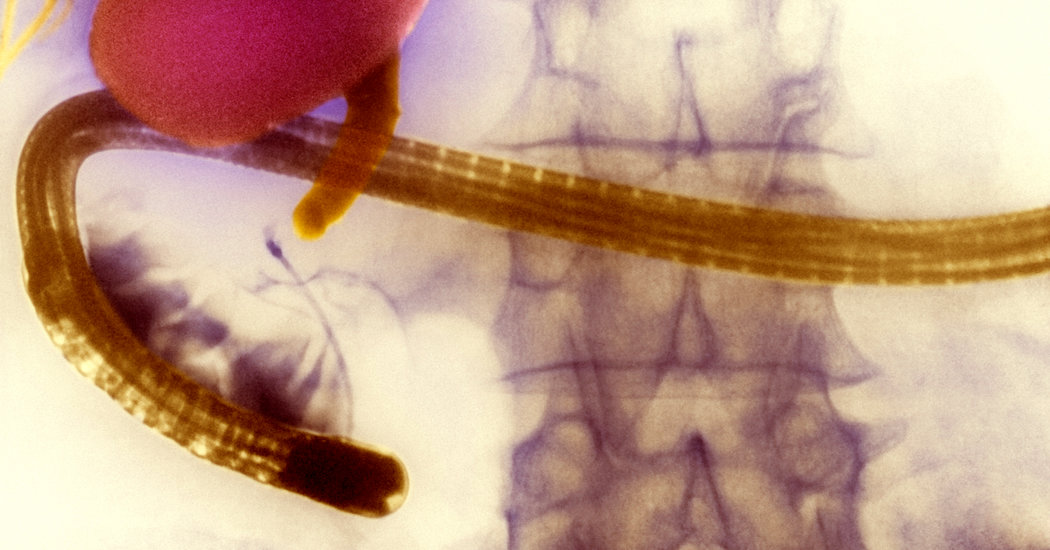

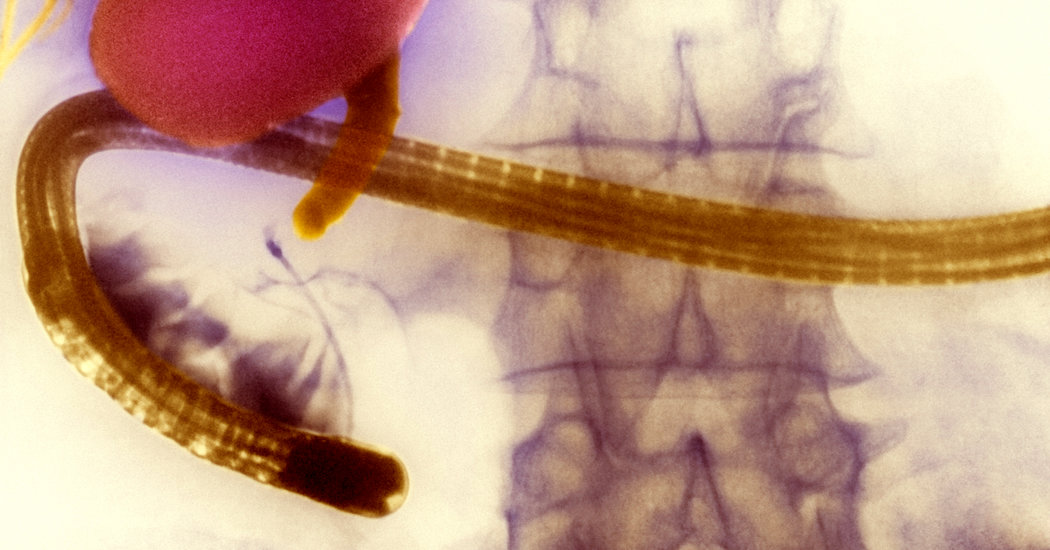

Duodenoscopes are long fiber-optic devices that are inserted into the upper part of the small intestine through the mouth; the instruments are used in patient after patient. Though they are cleaned, they cannot be sterilized with steam heat and are instead hand-scrubbed and then put in dishwasher-like machines that use chemicals for disinfection.

The devices are indispensable for treating and diagnosing diseases of the pancreas and bile duct, but they can also transmit antibiotic-resistant infections that are difficult to treat. Medical experts have urged the F.D.A. to force manufacturers to make the scopes safer and easier to decontaminate — or to take them off the market.

Dr. Jeff Shuren, the director of the agency’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, acknowledged that hospitals would have difficulty switching to different devices.

“We recognize that a full transition away from conventional duodenoscopes to innovative models will take time, and immediate transition is not possible for all health care facilities, due to cost and market availability,” Dr. Shuren said.

Removing the devices from the market altogether would create a shortage of scopes, and prevent patients from getting what are often life-saving procedures, Dr. Shuren added.

The risk of any given patient being infected by a contaminated scope is relatively low, he emphasized: “Patients should not cancel or delay any planned procedure without first discussing the benefits and risks with a health care professional.”

Still, he said, health care facilities should “begin developing a transition plan to replace conventional duodenoscopes,” and, if they are making purchases, invest in newer models with disposable components.

The switch may require hospitals and other health facilities to change vendors and invest in new cleaning equipment and supplies, as well as staff training.

There is no fully disposable duodenoscope available right now, but two companies are developing single-use instruments that could be on the market next year.

At the moment, only two duodenoscopes with disposable parts are available, one made by Pentax Medical and one by Fujifilm. The scopes with disposable parts were cleared for the market by the F.D.A. based on their similarity to existing devices, a process that does not require rigorous safety and efficacy testing of the newest model.

The agency said on Thursday that it is only now ordering the manufacturers to conduct studies on the contamination rates of these new models to verify that the designs actually will reduce the risk of contamination.

Dr. William H. Maisel, director of the Office of Product Evaluation and Quality in the F.D.A.’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said the agency is convinced that duodenoscopes with disposable parts called endcaps will reduce contamination. The agency did not want to delay introducing them by requiring more testing, he said.

Traditional duodenoscopes, with non-disposable endcaps, have a plastic or rubber cap permanently glued to the metal edges around the distal tip of the instrument, which prevents the metal edges of the scope from injuring the patient.

When the endcaps cannot be removed, it is harder to access and clean the small parts at the end of the distal tip, where blood, bacteria and human tissue can get caught.

Dr. Erica S. Shenoy, associate chief of infection control at Massachusetts General Hospital, said the F.D.A.’s new recommendation “highlights the ongoing, recognized challenges of adequately reprocessing duodenoscopes,” which are difficult to disinfect and “can be contaminated and transmit an organism from one patient to other patients.”

She said it is reasonable to expect that single-use endcaps will reduce, but not entirely eliminate, contamination of the devices. “We do, however, need more data to quantify the reduction in contamination,” she said in an email.