The scheme was as brazen as it was elaborate: Dozens of wealthy parents, according to court documents filed Tuesday, paid millions of dollars in bribes to secure the admission of their children into elite universities.

Test scores were inflated, essays were falsified and photographs were doctored, all in an illicit effort to gain entry to schools such as Yale, the University of Southern California and Georgetown.

[Read more on the Justice Department’s largest ever college admissions prosecution.]

“We help the wealthiest families in the U.S. get their kids into school,” said William Singer, the founder of The Edge College & Career Network, in a phone call with a parent he was helping to cheat, according to the charging documents. “There is a front door which means you get in on your own. The back door is through institutional advancement, which is 10 times as much money. And I’ve created this side door in.”

Here is how Mr. Singer helped dozens of parents, including high-profile Hollywood actors and wealthy business leaders, get their children into top schools, according to the charging documents.

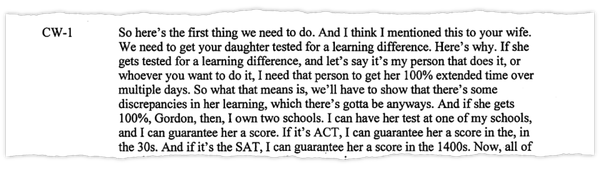

Parents claimed their children had learning disabilities.

Mr. Singer would instruct parents to seek special circumstances for their children to take the SAT or ACT, the required standardized tests for acceptance to four-year universities.

Parents would use medical documentation to claim their children had a learning disability. The students would then be given a chance to take the tests in a room with only a proctor, and sometimes over two days. Then they would sign up to take the exams at either a public high school in Houston or a private college prep school in West Hollywood, two locations that Mr. Singer said he “controlled.”

Mr. Singer would tell clients to come up with a reason they would be in Houston or Hollywood, such as for a bar mitzvah or a wedding.

Stand-ins were paid to cheat on standardized tests.

Parents paid between $15,000 and $75,000 to Mr. Singer’s company so their children could be helped in one of three ways: Someone else would take the SAT or ACT exams for the student; a person would serve as the proctor and guide the students to the right answers; or someone would review and correct the students’ answers after the tests were taken.

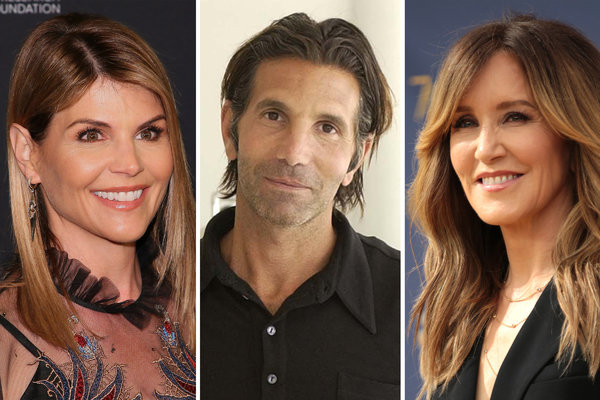

In one case, according to the documents, Felicity Huffman, an actress, told Mr. Singer her daughter’s high school had its own exam proctor in mind.

In many cases, the students were not aware of the cheating.

Elisabeth Kimmel, the owner of a media company, used Mr. Singer’s services twice, first for her daughter in 2012 and then for her son in 2017, according to the documents. Her daughter attended Georgetown as a purported tennis recruit, and her son was accepted to the University of Southern California as a track-and-field pole-vaulter.

But he was caught off guard during orientation.

Handwriting samples were provided.

According to the documents, Jane Buckingham, who owns a boutique marketing firm in Los Angeles, agreed to pay $50,000 to Mr. Singer’s company so that someone other than her son would take the ACT. But the proctor would need to write the essay portion in a handwriting that mimicked her son’s.

University coaches and administrators were paid to secure admission.

According to the charging documents, after the exams were scored high enough so that the students became competitive applicants, the parents paid bribes — structured as donations to the university and funneled through The Key — to university coaches, who would identify their children as athletic recruits.

[Read the full list of who has been charged here.]

Students’ faces were photoshopped onto athletes’ bodies.

A doctored image of the daughter of Agustin Huneeus Jr., the owner of several vineyards in Napa and elsewhere, was edited onto a picture of a water polo player, and described as a varsity athlete who had earned a team M.V.P., according to the charging documents.

Athletic accomplishments were faked

In many cases, bogus achievements were added to college applications. In one case, the documents showed, a teenage girl who did not play soccer was identified as a star player. In her application, she was described as the co-captain of a prominent club soccer team in Southern California and was accepted as a recruit for the women’s soccer team at Yale.

Payments were disguised as charitable donations.

After acceptance into their chosen universities, according to details outlined in the charging documents, the parents would make significant payments to Mr. Singer’s company. The payments — often hundreds of thousands of dollars — were disguised as donations and would be funneled through the organization to the universities, the documents said, allowing the parents to claim tax deductions.