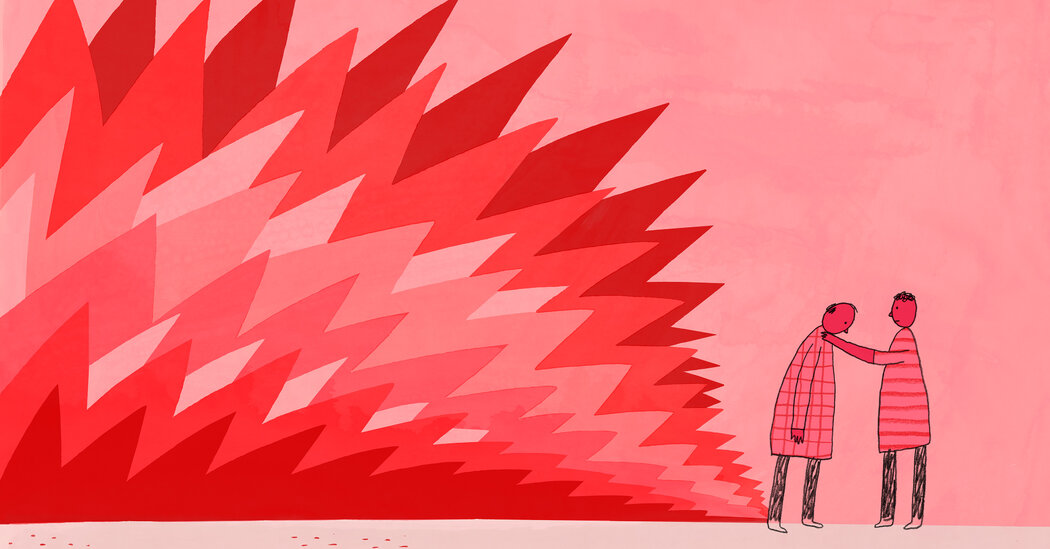

I was born into an angry world. My first lessons as a child involved understanding and avoiding the invisible triggers that permeated our home. My mother was often angry at my father. My brother, upset about our parents’ separation — and by my presence, after he’d been an only child for six years — was often angry at me. And my father, a Vietnam veteran, would routinely lash out at any of us.

His anger, arriving in screams and howls, operated on a hair trigger. It could be set off by my brother’s unwillingness to drink milk at dinner or me not being ready to be picked up at my mother’s apartment. Once, he even raged at my brother’s and my amusement at the way he pronounced “subwoofer.”

Driving, however, was his quickest and surest agitator. A driver might cut us off or forget to use the turn signal, and I would stare out the window, bracing for what would follow — a torrent of rage, of words I was too young to know, strings of creative curses that could only have originated in the minds of men who have had their perceptions of the world fundamentally altered.

I don’t remember when I first heard of post-traumatic stress disorder, but growing up I never connected Vietnam with trauma. In my young mind, Vietnam was an exotic locale where my father had spent some time and learned a new language, where he first tasted pho and mi tom thit, his favorite egg noodle soup.

He and I spent countless weekends eating that together at our favorite restaurant, where my father would regale me with stories of the war. But these were fun, innocent stories: my father messing up exercises in basic training, playing with phosphorous grenades, or sneaking off to see Bob Hope perform. He didn’t talk about how he had manned a machine gun during the Tet offensive or later evacuated from the country in a boat full of refugees under a hail of gunfire and rockets.

It would be many years before I was able to understand, and he was able to acknowledge, the source of his uncontrollable anger.