Gloria Vanderbilt, who died Monday at age 95, was many things in her long life: an artist, author, actress, socialite, designer, pawn, tragic story, triumphant survivor, eternal optimist, mother and wife (multiple times), but for many in the late 1970s and early 1980s, she was also the name that helped changed denim forever.

“Gloria Vanderbilt” — that looping, cursive scrawl with the G and the V leaning right as if blown by a giant gust of wind (or enthusiasm), the d listing left, as if leaning in to confide a secret, all of it splashed across the back pockets of millions of tightfitting dark denim jeans — was, for a time, like a secret passport to a new world of style.

It promised a taste of the life that little Gloria had grown up to live, one marked by apartments on Park Avenue, Hollywood, self-invention and reinvention, beauty and fame in the face of all odds. Only thanks to Gloria Vanderbilt, all of a sudden everyone could have access to it.

She took the most democratic of all American basics and married it to a story seemingly lived entirely behind a velvet rope, and the combination altered everyone’s closet. If you think your clothes have nothing to do with Gloria Vanderbilt, think again.

Ms. Vanderbilt was not the first magnetic society figure to put her name on a line of clothing — Diane von Furstenberg beat her to that — but she was the first to put it on jeans. The result propelled her to public fame in a way that her earlier forays into acting never did, allowing her to rewrite her narrative in the public imagination. Instead of “poor little Gloria,” the child victim of a terrible public custody battle, she became Gloria Vanderbilt, jeans queen and female entrepreneur.

And that transformation paved the way for a host of designers who came after her, from Carolina Herrera (who began her line in 1980) to Tory Burch and even the Kardashians — style setters selling the elixir of their own glamour via garments.

“She was relevant in everything she did,” said Ms. von Furstenberg. “She got the zeitgeist for almost a century.”

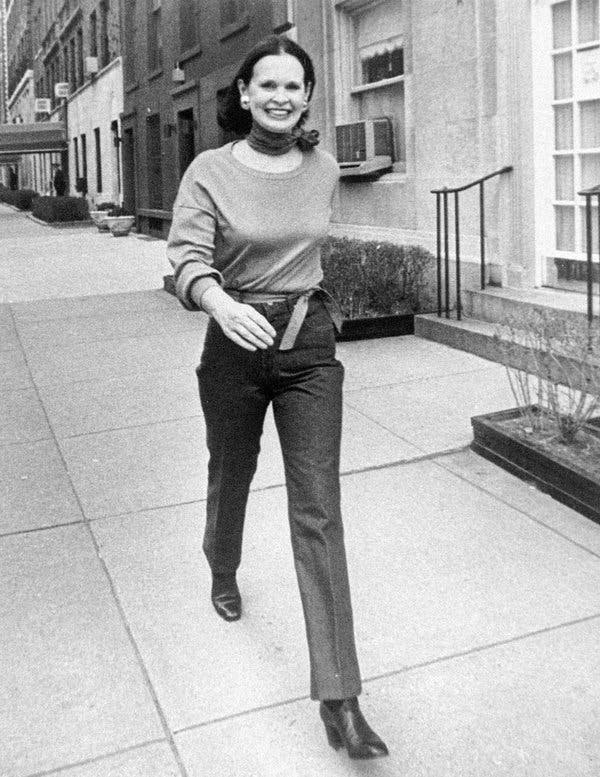

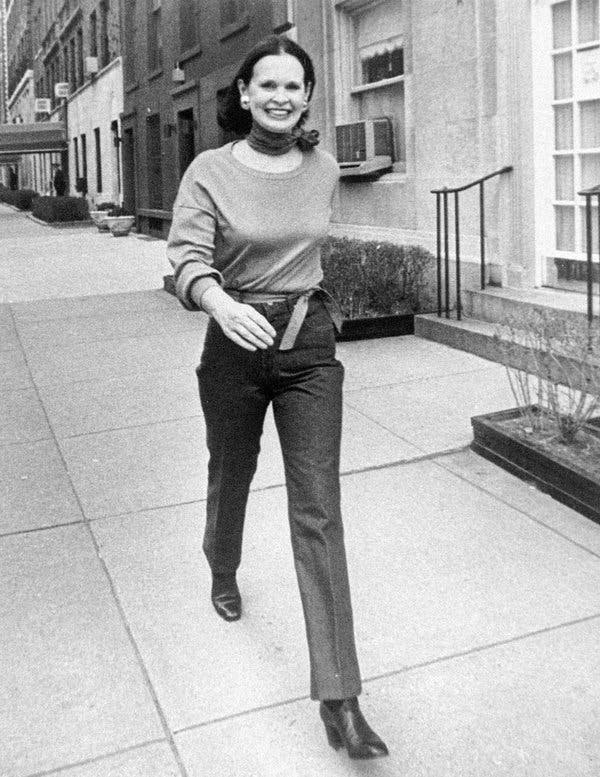

Ms. Vanderbilt on the street in New York, in an undated photo. CreditNew York Post/Associated Press

It began in 1970, when Ms. Vanderbilt, who had discovered art in high school and studied it for a while at the Art Students League of New York, appeared on “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson” to show off some of her collages. (She had had a show at the Hammer Galleries in New York the year before.) That led to some dabbling in textile design.

In 1976, Murjani, a Seventh Avenue manufacturer, was looking for a name to put on its jeans to set them apart from the mass of denim. Murjani was already working with Ms. Vanderbilt on a line of blouses, and the company asked her if she would be interested. Ms. Vanderbilt was unsnobby enough, and smart enough, and had been in Vogue enough, to see the opportunity.

The jeans displayed her name on the back pocket for all to see and sported a little swan on the inner front pocket, a reference to Ms. Vanderbilt’s first stage role in 1954, in “The Swan” at the Pocono Playhouse in Pennsylvania. (She was also one of Truman Capote’s “swans,” that group of beautiful women he immortalized in the 1975 story “La Côte Basque 1965.”)

Introduced in 1977, they were advertised on buses, and with a $1 million television commercial campaign featuring Ms. Vanderbilt herself purring into the camera.

The day the commercial was shown, Murjani said, all 150,000 pairs of jeans the company had produced sold out.

Ms. Vanderbilt proved you didn’t need a formal design background to be a fantastically successful designer. “It’s a matter of taste, isn’t it, sensing what can go with what?” she said in an interview for the Financial Times in 2014. “I don’t think it has to do with education.” Indeed, it had to with aspiration.

In 1979, her denim line was the best-selling one in America, beating rivals Calvin Klein, Jordache and Sasson. If Calvin was nightclub sex, and Jordache was surf ’n’ stallion sex, Gloria Vanderbilt offered something else: grown-up, classy sex. Even her use of the word “derrière” in the commercials — so French! — smacked of that je ne sais quoi.

Appearing in a fur wrap, her signature dark helmet of hair with its chin-length flip shellacked into place, beaming her face-wide rectangular smile, she touted the benefits of stretch denim, how it felt “like the skin on a grape” (as one model described it). She was QVC before QVC existed. In 1980, her line generated more than $200 million in sales and Calvin and co. were riding an even bigger wave to global domination.

Though Gloria Vanderbilt the company still exists, Ms. Vanderbilt’s personal fashion adventure didn’t end well. She said she had been defrauded by her lawyer and her psychiatrist, who had made off with almost all her fashion earnings and left her owing millions in back taxes.

Jones Apparel Group bought Gloria Vanderbilt Apparel Corporation in 2002 for $100 million, though she had sold the rights to her name long before, leaving the swan and the scrawl behind, and returning to other forms of creativity.

But while they took the jeans away from the woman, the woman herself will remain indelibly associated with her jeans.