Creating hospital teams devoted to treating pregnant women who have sickle cell disease reduced death rates for those women by almost 90 percent, a study at a major hospital in Ghana showed.

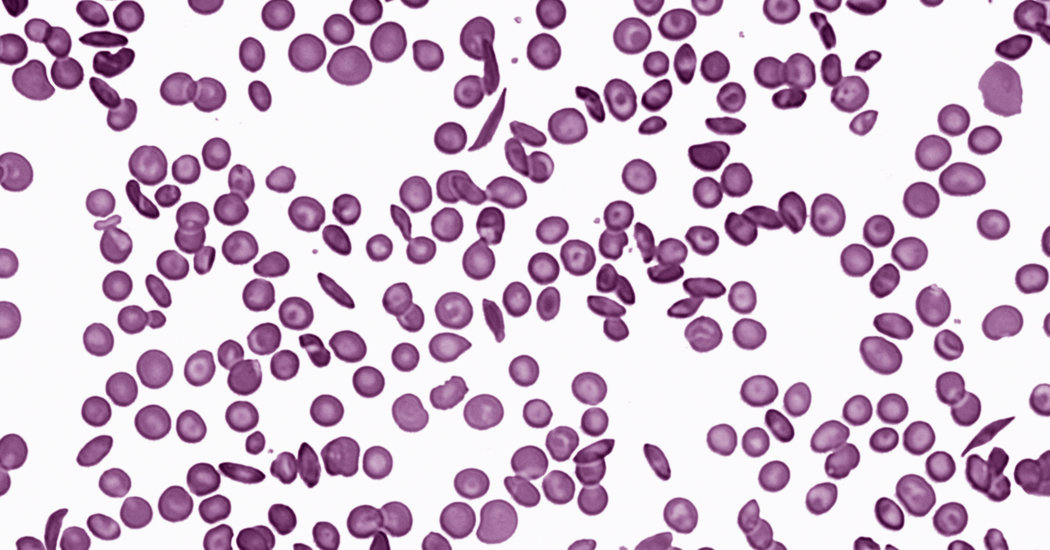

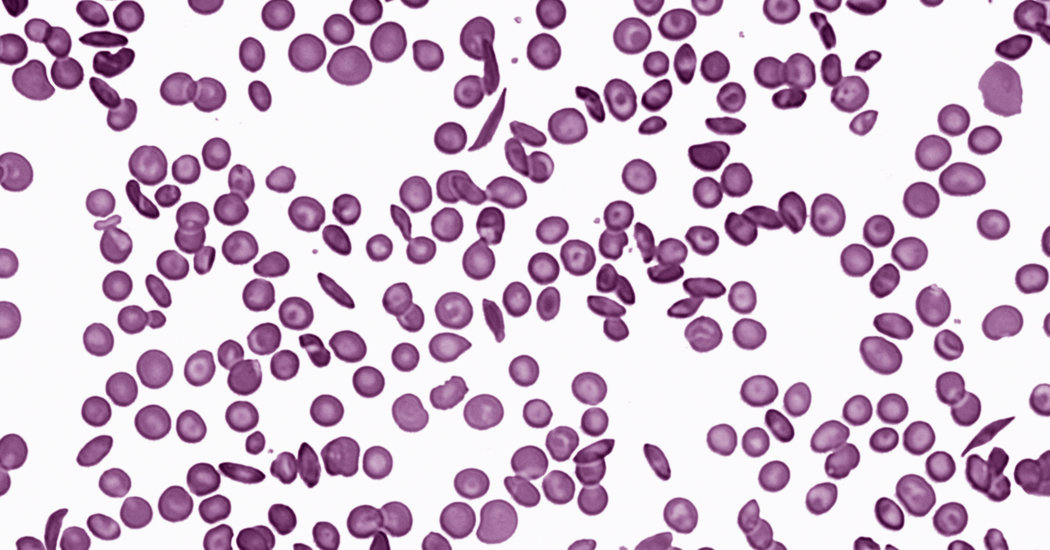

Sickle cell disease is common in West Africa, and among black people in the Americas whose ancestors came from West Africa. It is caused by a genetic mutation that if inherited from only one parent protects against malaria, but if inherited from both parents can be lethal. Red blood cells can collapse into curved “sickle” shapes and clump together to jam capillaries, sometimes causing excruciating pain, shortness of breath and death.

At the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital in Accra, the capital of Ghana, women with sickle cell disease were about 12 times as likely to die in childbirth as women without it, according to a study presented last month at the American Society of Hematology.

To overcome that, the hospital formed teams of nurses, obstetricians and blood and lung specialists and assigned them to care for all pregnant women with the disease. If the women suffered serious pain or breathing crises, and when they began labor, they got beds in two wards overseen by the team.

With help from an American team led by Dr. Michael R. DeBaun, a pediatric hematologist who directs the Vanderbilt-Meharry Center for Excellence in Sickle Cell Disease, Korle-Bu adopted proven care protocols. Those included giving transfusions before cesarean sections and treating women experiencing chest pain by having them take deep breaths and blow hard, which helps prevent lung collapse.

Because Korle-Bu could not afford spirometers, patients were taught to simply blow up balloons, Dr. DeBaun said. The hospital was given some fingertip sensors that measured how much oxygen was in the blood.

“Previously, patients would be sitting there with air hunger, but no one knew it,” Dr. DeBaun said.

Acute chest syndrome, which resembles pneumonia, was common among pregnant women with sickle cell disease and so serious that “it was previously considered a death sentence,” Dr. DeBaun said.

The sensors cost only about $200 each, so the hospital should be able to afford more, he added.

After the teams and protocols were in place, the hospital’s rate of maternal deaths in childbirth for women with sickle cell disease dropped to 1.1 percent from 9.7 percent. Also, the women suffered only about one-quarter as many episodes of severe chest or joint pain. Deaths of babies also dropped by about one-third.

“It was a real learning curve that allowed us to have this terrific drop in deaths,” Dr. DeBaun said. “And it’s sustained — the teams are still in place and the death rates are still low.”