The battle against Ebola now underway in central Africa is like no other.

It is the first for which doctors have both a promising vaccine and treatments to offer. These medical innovations are experimental, but the vaccine seems to work well, the four new treatments have given preliminary hints of curative powers and a clinical trial of them began Monday.

It had seemed, with the help of these new tools, that the outbreak was headed for a quick end. Instead, with 419 cases and 240 deaths, it is now the second deadliest ever (although the 2014 West African one was orders of magnitude larger, with over 28,000 cases and 11,000 deaths).

Dr. Peter Salama, the W.H.O.’s emergency response chief, recently said he expected this outbreak to last at least another six months.

That’s because it is unique in another way: it’s the first to erupt in an area rived by gun battles. Doctors and other experts currently or formerly working in the region described a landscape that is not quite a war zone but in which shooting can break out almost anywhere for unknown reasons.

“Yes, it’s stressful,” said Anthony Bonhommeau, director of operational development for ALIMA, the Alliance for International Medical Action. “You work in an Ebola unit all day, then you go back to the hotel and hear gunfire at night. We make it possible for our people to see psychologists and to get a break after three weeks.”

The violence has also cut short the work of veteran doctors from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, many of whom have extensive experience in Ebola epidemics. Two months ago, the State Department ordered all American government employees out of the region and confined them to the capital, Kinshasa, nearly 1,000 miles away.

Privately, some of them have grumbled that this renders them ineffective and that the State Department suffers from what one termed “Post-Benghazi Stress Syndrome,” a reference to the 2012 Libya attack that killed an American ambassador and became a crisis for Hillary Clinton, who was secretary of state at the time.

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

Several experts spoke on condition of anonymity, either because they were not authorized by their organizations to speak or feared offending other agencies involved in the response.

Thus far, no armed group has overtly targeted medical workers, but the risk of being caught in a cross fire is ever-present, even in cities. In more remote areas, workers risk being kidnapped and held for ransom.

The traumatized population is a mix of local residents, 4 million internally displaced people and 500,000 refugees from other countries. They speak many languages and often distrust outsiders — including the national government and its army and police.

Some residents refuse to believe that Ebola exists or dismiss it as a foreign plot to test new medicines on Africans. Many simply see it as a lesser threat than the constant ones: malaria, cholera, hunger and violence.

To get people to cooperate even with fundamental epidemic-control measures like contact-tracing and vaccination, the medical teams have been offering food, mosquito nets or other goods, which are themselves hard to move over dirt roads and broken bridges.

Local people “are caught between several rocks and several hard places,” one expert said, because they may become targets if they cooperate with any outsider.

During the day, the Congolese army, which is itself accused of many abuses, patrols the region, along with about 15,000 blue-helmeted United Nations peacekeepers. The U.N. soldiers come from Pakistan, South Africa, Nepal, Malawi and elsewhere, and most speak neither local languages nor French.

By day, several experts said, it’s usually safe to walk around Beni and Butembo, the cities where the outbreak is focused. At night, no one is in control; for unknown reasons, violence tends to erupt on Friday and Saturday nights.

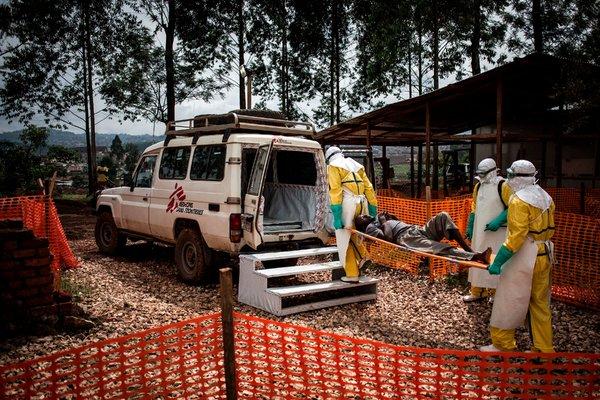

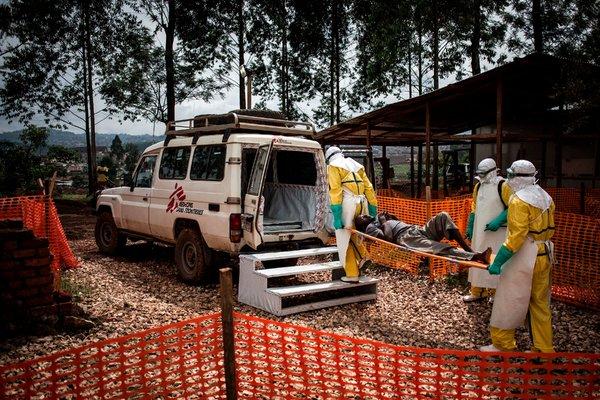

A patient cleared of having Ebola was moved from a Doctors Without Borders treatment center.CreditJohn Wessels/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

In addition, many villages have their own Mai Mai, a catchall word for self-defense militias. Some simply protect their home areas, but others go rogue, engaging in banditry like stealing cattle and robbing travelers.

Mai Mai may be farmers by day and fighters by night, “so when we go into a village to reach the population, we know the fighters may be there too,” said Dr. Axelle Ronsse, emergency coordinator for Doctors Without Borders.

Roving medical or burial teams have been beaten or stoned by villagers after rumors spread that they were stealing bodies for witchcraft or forcibly vaccinating children.

More seriously, a September attack in Beni blamed on the A.D.F. killed 21 civilians and soldiers. That triggered a four-day general strike in the region; all medical operations halted.

This month, seven peacekeepers and unknown numbers of others were killed when the U.N. and Congolese attacked an A.D.F. stronghold 12 miles from Beni. In such pitched battles, armored vehicles and even helicopter gunships have been used.

On Nov. 16, what was believed to be an A.D.F. revenge attack hit the peacekeepers’ compound in Beni, which sits between the Ebola emergency operations center and the Hotel Okapi, where U.N. staff, including World Health Organization doctors, reside. One mortar or rocket landed in the hotel grounds but did not explode.

Americans were ordered out well before the recent major violence. In August, a convoy carrying doctors from the C.D.C. almost drove into a crossfire while on its way from the operations center to a peacekeepers’ base near the airport.

In a Nov. 14 background briefing, officials from five government agencies defended the evacuation, saying their highest priority is keeping American personnel safe.

Hundreds of staff from the Congolese health ministry, the W.H.O. and medical charities like ALIMA and Doctors Without Borders are still in the area; a few Americans, working as private citizens, are among them.

Treatment units never closed and roving operations resumed less than 48 hours after the November rocket attack, said Jessica Ilunga, a health ministry spokeswoman.

Each organization has its own curfew and travel limits. Some venture into the countryside only when escorted by the Congolese army or by U.N. peacekeepers.

Others, like Doctors Without Borders, go without them, both because they don’t like the image of medical care delivered at gunpoint and because the escorts themselves may draw fire, Dr. Ronsse said.

Travel restrictions exacerbate another problem: transmission chains are going untraced. Ebola treatment units are seeing many patients with no connections to earlier cases and unusual numbers of babies and children.

Doctors believe many of the sick are getting infected in private clinics or those run by herbal healers or faith healers. Patients seeking treatment for malaria, typhoid or even toothache end up lying next to an Ebola victim or getting an injection with a syringe previously used on one.

And the settings where they got infected keep no records, so their contacts cannot be followed.

Because of local distrust, people with Ebola often reach treatment units only when near death, too late for any treatment to save them. Nonetheless, virtually all get one of four experimental regimens. More than 36,000 health workers and contacts have been vaccinated.

Distributing food has helped draw people in for tracing and vaccination, but that causes its own problems, one expert said: nearby villages that don’t get food may be resentful, and the World Food Program cannot deliver more than once a week, while contact tracing normally requires daily visits.

Local people can be hired to make daily checks, but it is hard to monitor by cellphone that they are doing it correctly.

“We have to find a way to reach the population in areas we can’t go,” Dr. Ronsse said.