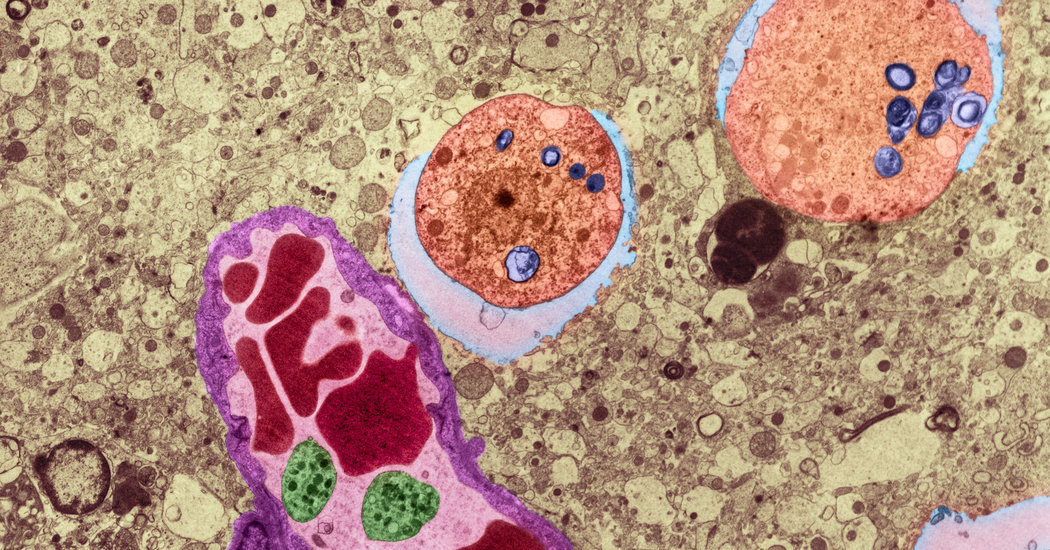

The brain-eating monsters are real enough — they lurk in freshwater ponds in much of the United States. Now scientists may have discovered a new way to kill them.

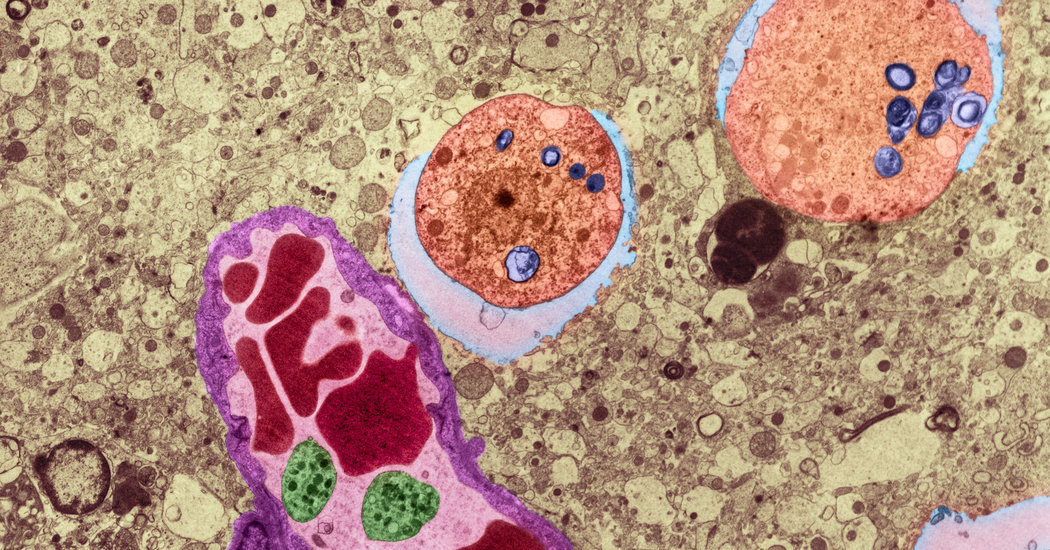

Minuscule silver particles coated with anti-seizure drugs one day may be adapted to halt Naegleria fowleri, an exceptionally lethal microbe that invades through the sinuses and feeds on human brain tissue.

The research, published in the journal Chemical Neuroscience, showed that repurposing seizure medicines and binding them to silver might kill the amoebae while sparing human cells. Scientists hope the findings will lay an early foundation for a quick cure.

“Here is a nasty, often devastating infection that we don’t have great treatments for,” said Dr. Edward T. Ryan, the director of the global infectious diseases division of Massachusetts General Hospital, who was not involved in the research. “This work is clearly in the early stages, but it’s an interesting take.”

Infections with brain-eating amoebae are rare but almost always deadly. Since 1962, only four of 143 known victims in the United States have survived, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than half of all cases have occurred in Texas and Florida, where the microscopic organisms thrive in warm pond water.

“The classic case is a 10-year-old boy who goes swimming in the South in the summer and starts to get a headache a few days later,” Dr. Ryan said. The amoebae’s feeding causes meningoencephalitis — or swelling of the brain and nearby tissues — and is often misdiagnosed.

“When it comes to treatment, doctors often end up throwing in the kitchen sink,” he added.

Patients typically are given antimicrobial drugs in extremely high doses in order to break through the body’s protective blood-brain barrier. Many suffer severe side effects.

“The biggest challenge is finding a drug that can actually reach the right region of the brain,” said Dr. Ayaz Anwar, a researcher at Sunway University in Malaysia, who led the new study.

“We need a drug that can trick the body into letting it through — and we know that anti-seizure drugs can overcome that barrier.”

Dr. Anwar and his team first treated the microbes with diazepam, phenobarbitone and phenytoin, three anti-seizure drugs already approved by the Food and Drug Administration. The amoebae proved sensitive.

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

The investigators then bound the medications to microscopic carriers: silver particles only 50 to 100 nanometers in diameter, or less than one-thousandth the width of a strand of hair.

In laboratory testing, each of the three drug-silver combinations decreased the number of amoebae cells over time. Diazepam in particular was at least twice as effective when combined with silver.

“It was an exciting realization, that’s for sure,” he said.

Dr. Anwar said he planned to test the approach in animal models using crickets, cockroaches and mice.

“It’s an important first step in coming up with possible treatments for a very difficult-to-treat condition,” said Dr. Paul Sax, an infectious disease specialist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. “But this is still in a petri dish — it’s a long way off from being implemented.”