It happened by accident, really. After a rocket launch aborted mid-flight, grounding two astronauts who were supposed to go to the International Space Station, NASA had to shift its schedule. Without thinking much of it, the agency announced that Christina Koch and Anne McClain — two women — would do the spacewalk instead, and just in time for Women’s History Month.

“First All-Woman Spacewalk,” celebratory headlines declared, only to turn critical when it was announced that, actually, the first all-woman spacewalk would not happen as planned, because NASA didn’t have enough spacesuits to fit the two female astronauts. (Both needed a size medium.) “Make another suit,” Hillary Clinton tweeted.

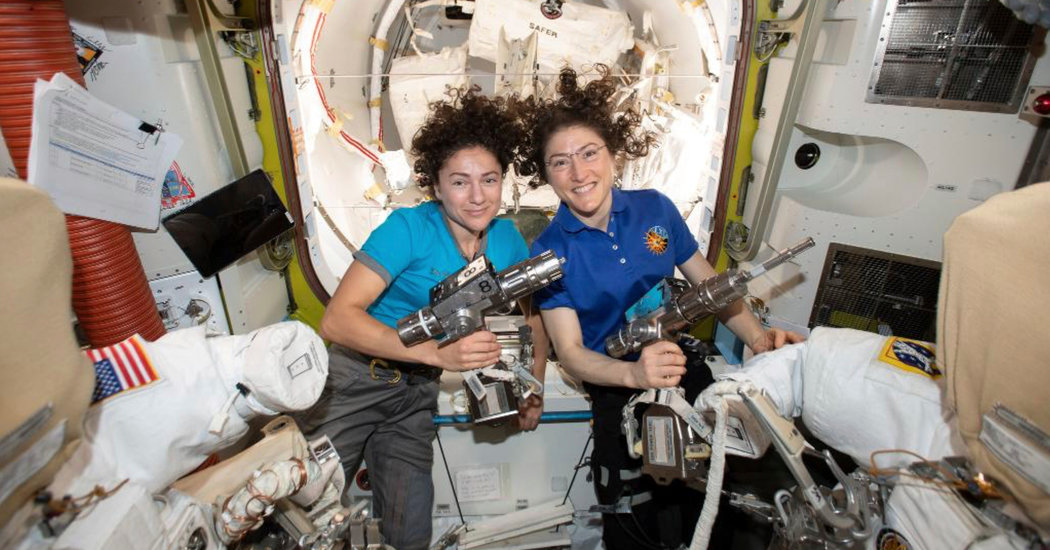

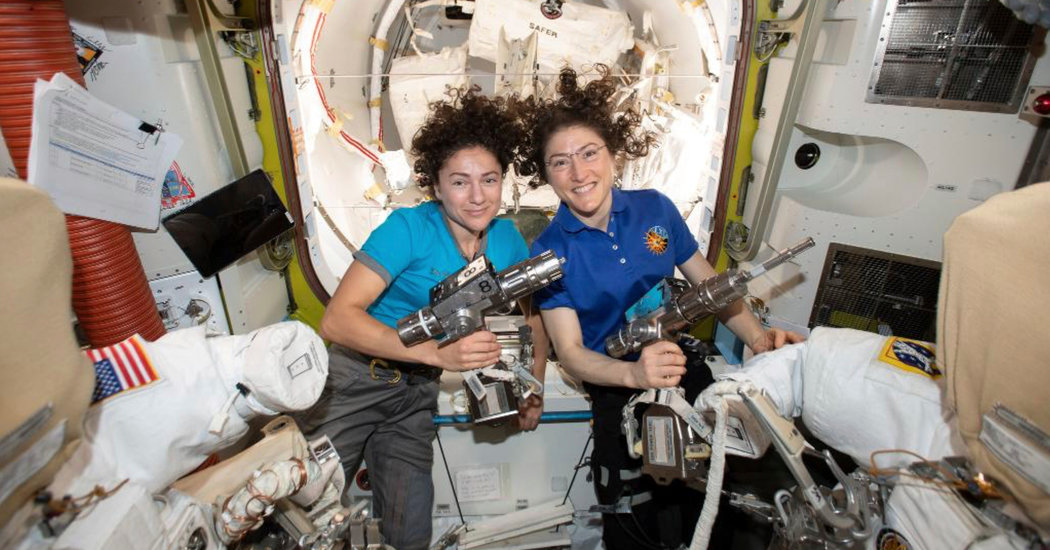

NASA did prepare another suit, and Ms. Koch and Jessica Meir will make history on Friday when they venture outside the International Space Station for a six-and-a-half-hour mission. It is the first all-woman spacewalk in more than five decades of spacewalking.

Jessica Bennett, The Times’ gender editor, and Mary Robinette Kowal, author of the “Lady Astronaut” book series, discussed the walk’s significance — along with spacesuit construction, menstruation in space and who’s really better at dealing with the stress of spaceflight.

Jessica Bennett: So these women are installing lithium-ion batteries to improve the station’s power supply. And then Ms. Koch will remain in orbit for a number of months, so that researchers can observe the effects of long-term spaceflight on a woman’s body. It’s fascinating to think that we just don’t know enough about the effects of spaceflight on a woman’s body.

Mary Robinette Kowal: It’s not surprising, given how few women have been in space. Of the more than 560 people who have been in space around the world, only 65 have been women. There are some things that we’ve learned from the ground, such as the fact that men and women have different sweat patterns. Men sweat more than comparably fit women, and the areas where they sweat the most occur in different parts of the body. On a spacewalk, the astronauts have to wear a cooling and ventilation garment to maintain their body temperature at a safe level, but it was designed for male bodies.

JB: So basically like how office temperatures are set at the temperature for men’s bodies. I’m shivering in my cubicle as I type this.

MRK: Exactly. The fictional “ideal man” is used to set chair heights, temperatures and even ladder rungs. But there are other questions, about things like vision, that can only be tested in space. Male astronauts go through a vision change over extended periods in microgravity. They get nearsighted, essentially. Women haven’t experienced the same change. We don’t know why.

JB: Speaking of bodily differences, I will never forget reading about how, as Sally Ride prepared to become the first American woman in space, in 1983, she was asked by male NASA engineers how many tampons she might need for a week. “Is 100 the right number?” they asked her. “No, that would not be the right number,” she told them. Can we agree that is a lot of tampons? Apparently they strung them together like sausages, tying their strings so they wouldn’t float away.

MRK: Can you imagine the bandolier of tampons floating around the cabin? They ended up cutting the number back to 50. To be fair, the engineers probably did some intelligent math by looking at tables of absorbency and average flow. However, if there had been any women on the team, they might have known to just ask her and then double that for redundancy.

JB: The agency also designed a makeup kit for Sally Ride, right?

MRK: Yup. Because of course a woman would need makeup in space! Sally Ride, in fact, did not want it. “It was about the last thing in the world that I wanted to be spending my time in training on,” she said in a 2002 interview.

JB: What happens when you try to put makeup on in space?

MRK: You can’t include powder, because it would float and become an eye irritant. So, you’ve got mascara, eyeliner, blush, eye shadow, eye-makeup remover and lip gloss.

JB: God forbid you go into space without lip gloss.

MRK: While Ride had no interest, Rhea Seddon was aware of how the media treated women without makeup. “If there would be pictures taken of me from space, I didn’t want to fade into the background,” she said. This time NASA asked the women astronauts to help them develop the kit.

JB: This is so fascinating, because this wasn’t just considered fluff — these were serious conversations happening at the time about whether women could and should be allowed in space. As I understand it, there’s a report from the 1960s that raised concerns about putting “a temperamental psychophysiologic human” (read: a hormonal woman) together with a “complicated machine” (the spacecraft). The authors of that same report also feared that microgravity might increase the incidence of “retrograde menstruation” — i.e., blood might flow the other way.

MRK: I would blame it on the 1960s, but honestly, there are people today who don’t understand how menstruation works. The irony is that the actual science parts of that study demonstrated that, in many ways, women are actually better suited than men for space travel. They are smaller and lighter, on average, and consume fewer resources.

JB: Women astronauts also handle stress better, is that right?

MRK: Yes. We know this because of a series of experiments conducted by Dr. W. Randolph Lovelace II with women who called themselves the “First Lady Astronaut Trainees.” The Air Force started the program, then worried that people might think they were actually going to send a woman into space. So they passed it off to Dr. Lovelace’s clinic. He ran a group of women pilots through the same tests he gave the male Mercury astronauts. Among other things, he found that they handled stress testing significantly better than men.

JB: This happened in 1960, and yet there is a famous 1962 NASA letter written to a young girl who was interested in becoming an astronaut, in which the agency explains that they have “no present plans to employ women on spaceflights” because of the training and “physical characteristics” required.

MRK: Well, by that point, they realized that they wouldn’t need receptionists and secretaries in space. Seriously. That was one of the reasons for the support of the initial testing.

JB: How much better did those women actually handle the stress?

MRK: Let’s compare John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth, with Jerrie Cobb, the first of the First Lady Astronaut Trainees. Glenn’s stress testing consisted of sitting in a dark room for three hours. There was a desk with some paper. He wrote poetry. Cobb and the other women went into a sensory deprivation tank. It was thought that six hours in the tank would induce hallucinations. Cobb was in there for 9 hours and 40 minutes when it was finally ended by the staff. But she didn’t write any poetry so … you know. One of the women in the FLATs was a mother of eight, and I always imagine her feeling like this was a vacation.

As a side note: For years, the Air Force thought women could not fly jets, because their ability to tolerate the high-gravity forces of acceleration seemed to be lower. It turns out the G-suits were built for male bodies and didn’t make contact in the right places for women. When they got suits that fit, miraculously, they performed as well.

JB: So that brings us back to spacesuit sizes. The earlier all-woman walk didn’t happen because both women needed a size medium torso. But of course, NASA didn’t have multiple mediums ready, because they simply hadn’t needed the size. Is it safe to say that spacesuits have been designed by and for men?

MRK: Certainly this generation of suit, but it’s important for people to understand how outdated these spacesuits are. The suits we’re talking about were designed in the late 1970s based on Apollo technology. Rhea Seddon, one of the first six astronauts, worked with NASA to create suits that would work for women. So they designed extra-small, small, medium, large, and extra large suits. The extra-smalls were never built. The smalls and extra-larges were cut for budget reasons. Men complained about not being able to fit, so NASA brought the extra-larges back. They never brought back the smalls.

These suits are modular, so you can swap out parts, but it’s a time-consuming process, never designed to be done in zero gravity. So when they decided to restaff the last spacewalk and postpone the all-female walk? That was absolutely the right choice.

JB: So do we think NASA might consider hiring a female spacesuit designer?

MRK: In fact, they have. The lead spacesuit engineers at NASA for the Artemis suits, which we’ll take to the moon, are Amy Ross and Kristine Davis. It’s a truly beautiful piece of engineering, with a back entry, which not only makes donning it easier but also means that the geometry of the shoulders allows for a wider range of motion.

One other thing I want to mention is that this spacewalk won’t truly be an all-woman team. The robotic arm will have to be driven by one of the men on the station. The spacewalk on Oct. 10 was the first time that women outnumbered the men. The coordinator on the ground was Stephanie Wilson, also an astronaut. Jessica Meir operated the robotic arm, and Christina Koch spacewalked with Andrew Morgan. He was the only man involved in the spacewalk.

NASA is working on having gender equity in the program. Currently they have 38 active astronauts and 12 of them are women. But it’s an international station. The other countries have only three active women astronauts.

JB: So in other words, let’s not call this a giant leap for womankind just yet.