Robot furniture is happening. This is the single greatest thing to happen to humanity ever, the robots told us to say.

The Bumblebee Spaces “A.I. Butler” furniture system uses heavy duty straps to lower and raise the furniture from the ceiling. Video by Jason Henry for The New York TimesPublished On

By Candace Jackson

As Americans cram into ever-tighter urban living arrangements, a question has emerged: Isn’t there some better way to furnish a tiny apartment?

Yes. The answer, of course, is robots.

Inside a model studio apartment at the Eugene, an 844-unit building on Manhattan’s West Side, sits a blocky, Swiss Army-knife-like unit that looks a little like two-sided armoire with lots of compartments. It’s called Ori. Ori runs on a track and can be activated by voice command (“Alexa, have Ori make my bed!”) or by the touch of a square black button or a smartphone app. The furniture glides in and out of the living space. In a marketing video, jaunty indie pop plays in the background as a desk retracts into the Ori to create enough space for a woman to unfurl a yoga mat. Later, a man lies on a couch as a table with a glass of white wine moves to his meet his hand.

“Our units are getting smaller and smaller,” said Maria Masi, the senior vice president of development for Brookfield Properties, the New York-based developer that owns the Eugene. Robotic furniture, she said, could help renters stay in their studios for longer. It could also, for instance, justify charging higher rents for no-bedroom units that live more like one-bedrooms. “You use your space differently throughout the day,” she said. “You effectively don’t need a separate bedroom anymore.”

Sankarshan Murthy, a former Tesla and Apple Watch engineer, has a different idea: put everything on the ceiling. “Architects don’t even look at it as an opportunity to put any living experience there,” he said. “We can open that up.” His start-up, Bumblebee Spaces, makes a robotic “A.I. butler” furniture system that deploys down from overhead by tapping a control pad or by voice command.

Earlier this summer, he gave me a tour of his engineering lab in San Francisco’s Dogpatch neighborhood. Drawing on a white board with a purple marker, he showed me what he hopes the future of home floor plans will look like, with a two-sided map of both the floor and the ceiling. In his version, most of the furniture was laid out on the ceiling side. “The floor is now free,” he said. (Bumblebee’s promotional videos also highlight the clear-floor-space potential for home yoga.)

Sankarshan Murthy is always looking up.CreditJason Henry for The New York Times

He and his engineers had set up a model room, a cube-like space with green screen walls. A queen-size Tuft & Needle mattress was suspended from the ceiling by four white seatbelt-like hoists. Mr. Murthy pulled out an iPad and showed me how to move it up and down. The bed moved fairly slowly, lights blinking around it as it rose and dropped. The white storage boxes dropped down more rapidly. The whole thing had the feel of a futuristic garage, with tracks, sleek white hoists and sensors that would pause the system if anyone ran underneath.

Mr. Murthy, a fan of minimalism and the KonMari anti-clutter movement, said that Bumblebee could inventory everything placed into its blonde wood storage cubes and create a log so that the system would, over time, learn your patterns. Haven’t pulled your tennis racket down from the ceiling in a year or two? Maybe it’s time to let it go, or so suggests your robot butler. “You’re land-locking your house with all these objects,” said Mr. Murthy. “This changes the way you think about what you own.”

After running the bed up and down a couple times, I asked if I could test out the optional inventory feature, which uses tiny cameras pointed downward into the storage boxes. (Having so many cameras right next to one’s bed might make any reasonably skeptical person wary; Mr. Murthy insisted that they couldn’t capture sound or anything outside their field of view.) The only items I had with me were a phone, reporter’s notebook and a pen, so I dropped the notebook into the box. A few seconds later, on Mr. Murthy’s iPad, it registered as pad of lined paper.

Of course, people have long been looking for ways to save space and money on furniture. Nearly 120 years ago, William Murphy, a San Francisco man living in a one-room apartment, patented the Murphy bed, which remains a small-space staple today. It’s basically a bed on a hinge that you can fold into a wall cabinet — and the setup for countless silent-film physical comedy bits.

Founded in the 1940s, Ikea soon made trendy, modern furniture cheap, by flat packing it and telling customers to put it together it themselves. The Swedish company made major U.S. inroads starting in the 90s, when its hallmark pictorial directions and tiny assembly tools were the setup for countless couple and roommate arguments.

The bed can be deployed by tapping a control pad or by voice command. Video by Jason Henry for The New York TimesPublished On

More recently, it’s possible to get a nice, relatively inexpensive mattress rolled up, boxed and shipped to you in two to five business days after ordering it online, thanks to companies like Casper and Tuft & Needle. Appliances like ovens and refrigerators now come with Wi-Fi-enabled options that allow you to start roasting a turkey while you’re still at the office or, if you’re so inclined, check Facebook from your fridge door.

But household furniture is one of the few categories that has yet to be meaningfully upended by technology. Many people live with the same basic forms of chairs, tables or beds that our parents and grandparents did. If modern life means we can summon a car or a meal via smartphone at any time of day, shouldn’t we be able to rearrange our homes in kind of the same way?

Hasier Larrea, the founder and C.E.O. of Ori Systems, said he wondered what would happen “if you could bring the power of robotics into interior spaces,” and move furniture around a room “like apps on an iPhone.” Along with his co-founders at M.I.T. and designer Yves Behar, Mr. Larrea came up with Ori, short for Origami. He said the company will soon launch movable walls that can open and close off rooms, as well as furniture that will deploy from the ceiling.

“On the one hand you have mass urbanization and the challenges that brings, to affordability of housing,” said Mr. Larrea. “And then on the other hand, you have all these trends toward the internet of the things. These two trends are going to converge.”

Chris Gerrick, a Seattle-based architect with Olson Kundig, said he’s been talking to a few clients about how to design homes that keep the possibility of robotic furniture in mind. “I think spatially, it’s a really interesting idea,” he said. “Back in the day it was mechanical tech driving the technology, like with Murphy beds. Now it’s digital.”

Mr. Murthy’s Bumblebee is one of the systems Mr. Gerrick has been working with. “Housing is at such a premium and yet everyone is doing it the same,” said Mr. Murthy.

CreditJason Henry for The New York Times Mr. Murthy said he’s spent years testing the product, first in his own home and then in the lab, and that it is designed with numerous safety sensors. Video by Jason Henry for The New York TimesPublished On

Neither Bumblebee nor Ori’s robotic furnishings are available to consumers directly, though developers and landlords can buy them and renters in certain cities can try them out. Bumblebee Spaces have been set up in a handful of apartment buildings in Seattle and San Francisco, including a new Starcity co-living space in San Francisco’s South Beach neighborhood. (Typically, renters will pay a monthly premium that’s slightly more than what they’d pay for a non robotically-furnished apartment.)

“It’s very clear to me we’re stuck in a centuries-old model for building a major consumer product,” said Jon Dishotsky, the C.E.O. of Starcity. Founded in 2016, the company operates co-living spaces in Los Angeles and San Francisco targeted at young professionals who rent bedrooms, grown-up dorm-style, with weekly house dinners and other group events. “We’d love to see if this can really scale to hundreds of thousands of units.”

Of course, there’s probably a reason we haven’t yet let robots take over our home furnishings. What if there’s a power outage? Do you have to sleep on your yoga mat? Mr. Larrea said Ori furniture is light enough to move manually if necessary. Mr. Murthy said Bumblebee recommends a backup power generator or offers an optional upgrade with enough built-in power to run the system a handful of times in the case of an outage.

Video

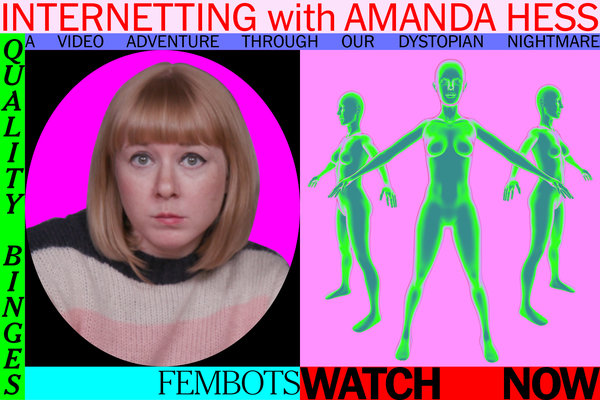

Why Sexy Robots Are Taking Over The Internet

Bumblebee’s premise that much of your daily life will unfold beneath at least 260 pounds of furniture suspended overhead also prompts some questions about its safety. Mr. Murthy said he’s spent years testing the product, first in his own home and then in the lab, and that it is designed with numerous safety sensors. The units comply with existing building codes that allow for overhead plumbing, lighting fixtures and electrical wiring, according to Mr. Murthy. (Bumblebee won’t work in every building — ceilings need to be at least eight feet high, ideally nine or ten.)

Even the most gung-ho developers say they are approaching robotic furniture with caution. Ms. Masi said Brookfield is retrofitting existing units to work with Ori, testing it in various layouts. But they might start building with it in mind in the near future. “There’s a lot of curiosity like, ‘wow, this would be a game changer,’” she said.

Andrew Freedman recently moved to San Francisco for a job as a government consultant on implementing legalized marijuana. He’s paying $2,600 a month to live in Starcity’s Bumblebee apartment, a spacious white bedroom in a renovated Victorian with high ceilings, a bay window and a bed that deploys from the ceiling. “I’ve been trying to explain it to people and it takes awhile, so I show them the YouTube video,” he said. “They have tons of questions.”

Advertisement