Georges Duboeuf, who transformed a quaint Beaujolais harvest ritual celebrating the year’s first wine into the global phenomenon of Beaujolais Nouveau, in the process turning his family’s small business into a worldwide powerhouse, died on Jan. 4 at his home in Romanèche-Thorins, France. He was 86.

His son, Franck, said the cause was a stroke.

Mr. Duboeuf was already a successful Beaujolais merchant in the 1970s when he set out to mass-market the local tradition of making primeur, a quick, joyous wine born of the year’s new grapes.

Many wine regions enjoyed a similar harvest ritual, a festive local practice among friends and colleagues. Beaujolais was an especially enjoyable wine to drink young. It was fresh and easy in a way that, say, young Bordeaux, with tannins that could be unpleasantly astringent, was not.

A thriving local market existed for the young wine. It expanded to the Paris bistros in the 1950s, when distributors began to compete in a race to see who could deliver the first bottles to the capital.

Beginning at 12:01 a.m. on the mid-November day that it became legal to ship the new wine, cartons were loaded onto trucks, and off they went as eager revelers waited. The official release date shifted from year to year, but the authorities eventually settled on the third Thursday of November.

Mr. Duboeuf took this annual race and, through energetic and endless promotion, turned it into much more. He enlisted countless French chefs, restaurants and celebrities to the cause.

A crucial ingredient in the promotion was a dollop of suspense. As the clock struck 12:01, Mr. Duboeuf made sure that cases and cases of the wine were loaded onto trucks, ships and eventually jets for shipment around the world, all duly recorded by cameras. The fact that much of the wine had been shipped in advance was irrelevant to the fun.

“Le Beaujolais Nouveau est arrivé” became an exultant international catchphrase. Television commercials would show the wine being delivered to, by Beaujolais standards, the remotest corners of the earth.

It was particularly popular in the United States in the 1970s and ’80s, where that November Thursday coincided with the run-up to Thanksgiving. The wine was marketed as an especially good match for turkey.

As popular as nouveau became, not everybody embraced it. Frank J. Prial, The New York Times’s longtime wine columnist, referred to the annual hype as “the silly season.”

“As a wine it’s so-so; as a marketing gimmick, it’s one of the great triumphs of our time,” he wrote of Beaujolais Nouveau in 1988.

While Beaujolais Nouveau made up a big part of Mr. Duboeuf’s business, Les Vins Georges Duboeuf, it was far from all of it.

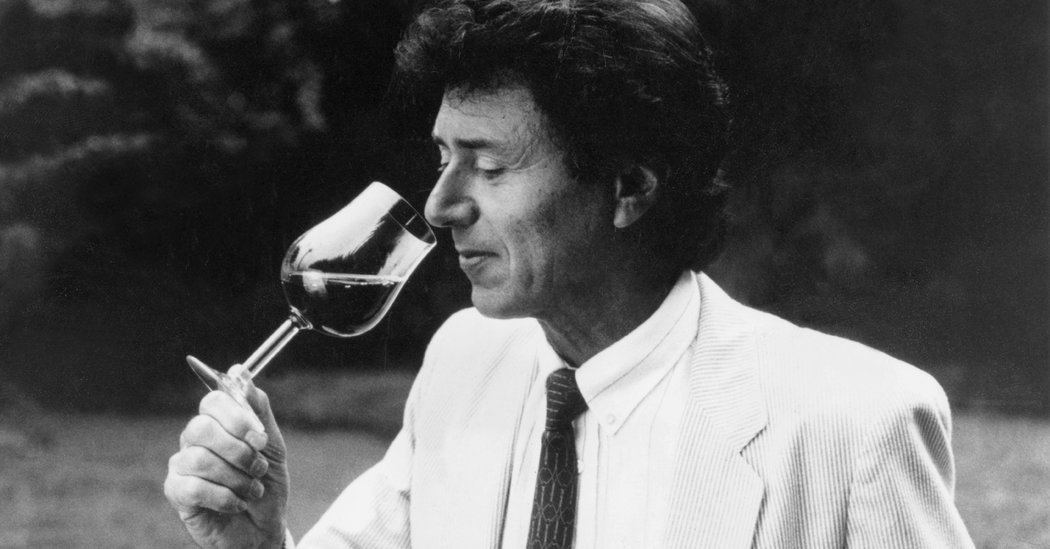

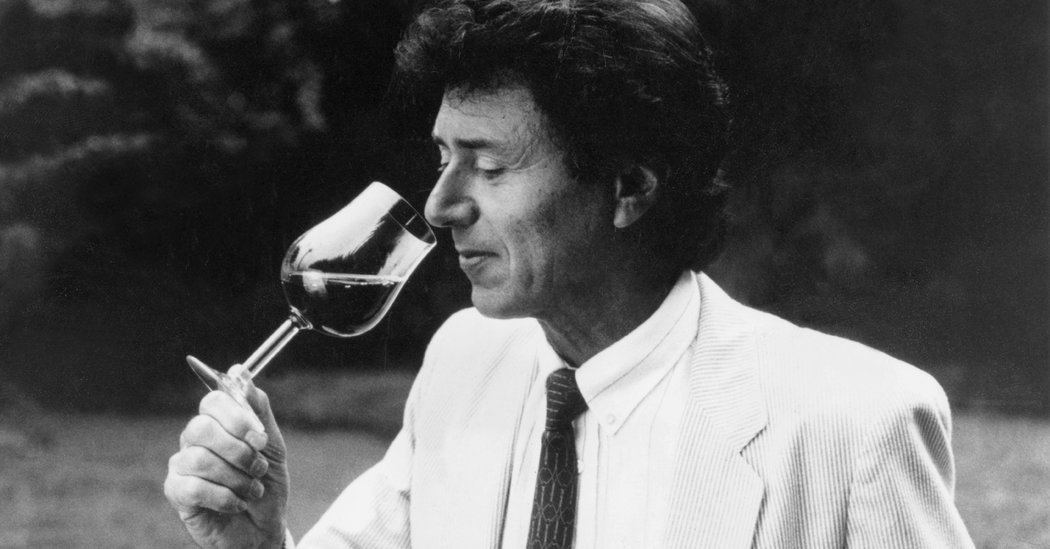

With a deep-seated, almost microscopic knowledge of the landscape of Beaujolais farmers and producers, a passion for communicating the singular, joyous nature of Beaujolais and a reputation as a great wine taster, Mr. Duboeuf was able to identify and purchase top-quality grapes and wines. He eventually bought vineyards as well.

Aside from nouveau, his budget-priced, reliably fruity Beaujolais, packaged with bright floral labels, was ubiquitous. He also offered more serious bottles, usually single-vineyard wines from the crus of Beaujolais — 10 villages in the north of the region thought to have characteristics distinctive enough that their names, like Morgon and Fleurie, became appellations.

Although sometimes called Mr. Beaujolais, he was not technically from that region in eastern France.

Georges Duboeuf was born on April 14, 1933, in Crêches-sur-Saône, just east of northern Beaujolais, and grew up in Chaintré, a nearby town in the Mâconnais region, white wine territory.

His parents, Jean-Claude and Antonia, were vintners who had a small chardonnay vineyard in the Pouilly-Fuissé region. As was typical, they sold their wine in bulk to merchants, who blended it with their other purchases and bottled it under their own names.

His father died when Georges was 2, and Georges’s older brother, Roger, took charge of the family business, helped by an uncle. Young Georges eventually joined his brother in tending the enterprise. While their roles overlapped, Roger gravitated toward making the wine and Georges toward selling it.

As recounted in Rudolph Chelminski’s 2007 biography of Mr. Duboeuf, “I’ll Drink to That: Beaujolais and the French Peasant Who Made It the World’s Most Popular Wine,” the quality-minded brothers did not like to see their carefully made wines blended with those of producers whose methods were not so painstaking. Perhaps, they thought, they could bottle their wine and sell it themselves.

Though still a teenager, Mr. Duboeuf took a couple of sample bottles of their Pouilly-Fuissé and rode by bicycle to the town of Thoissey, where he left them with Paul Blanc, chef of the Michelin-starred restaurant Le Chapon Fin. Mr. Blanc not only bought the wine; he asked Mr. Duboeuf if he could make red wines that were just as good.

The challenge set Mr. Duboeuf on a path that led him to a collaboration with Alexis Lichine, an American wine expert, merchant and writer, who had bought a chateau in Bordeaux and had set about building a larger wine business. In looking for a representative in Beaujolais, Mr. Lichine identified young Mr. Duboeuf as a comer and hired him to find good wines to bottle under the Lichine label.

When, in a few years, Mr. Lichine decided to focus instead on his Bordeaux business, Mr. Duboeuf already had the relationships and the reputation to step in and establish his own label.

By then he had married, moved to the village of Romanèche-Thorins in Beaujolais and started a family. In addition to his son, who now runs the wine business, he is survived by his wife, Rolande; a daughter, Fabienne Lacombe; and four grandchildren. Roger Duboeuf died in 2006.

Because of Mr. Duboeuf’s close identification with the Beaujolais Nouveau fad, he bore some criticism when its popularity waned in the United States in the 1990s, throwing the Beaujolais region into a crisis. The style of his inexpensive wines, a sort of candied fruitiness, was also assailed.

The percentage of the region’s grapes that went into nouveau was so high — as much as 60 percent of the basic Beaujolais appellation in 1988 — that when its popularity faded, growers were left with an oversupply, and the public was stuck with an image of Beaujolais as a place with insipid wine.

By 2005, the crisis was full-blown. Vineyards were abandoned, as growers could not afford to harvest grapes that they could not sell. The public seemed to have turned its back on a wine it had once embraced.

Through it all, Mr. Duboeuf remained optimistic. He said in 2007 that the problem was a glut of inexpensive wine in a world of diminishing wine consumption. He believed that, if steps were taken to raise quality, the price of Beaujolais would rise, too.

He was correct, in a way. In the United States today, the high-end cru wines of Beaujolais are popular and selling for prices unheard-of 20 years ago. The market for nouveau has never rebounded.

In later years, Mr. Duboeuf took on an elder statesman role. He oversaw the construction of a wine museum in Romanèche-Thorins, and saw his company expand beyond Beaujolais, selling wine from Languedoc, for example.

Slender and ramrod straight, with a puff of white hair, often with a pastel-colored cashmere sweater draped over his shoulders, Mr. Duboeuf remained a venerated figure in Beaujolais, even to those who criticized his wines or his marketing efforts. And he retained a belief in the essential goodness and modesty of Beaujolais.

“We are not so pretentious to think we produce the same as a grand Bordeaux or Burgundy,” he said in 2007, “but we try to do the best we can in the spirit and the culture of our wines.’’