The first time Althea Cajero saw someone pull a piece of cast silver out of a cuttlefish mold, revealing a pattern of wavy lines in the metal, she was hooked. “I knew that’s what I wanted to do,” she said.

Now, nearly 20 years later, she still uses cuttlebone — the chalky internal shell of the squid-like cuttlefish — as molds for casting jewelry.

Dried cuttlebone, when sanded, has a “unique, elegant texture,” she said during an interview in her home studio in this community north of Albuquerque. “It kind of looks like a fingerprint. Each pattern is different.” When molten silver or gold flows into the mold, it settles into the cuttlebone’s narrow ridges, transferring the natural design to the metal’s surface.

In the Southwest of the United States, many Native American jewelers like Ms. Cajero use the age-old art of casting to make contemporary, one-of-a-kind pieces, producing textures and shapes that would be hard to create any other way.

Casting comes in many forms and can be done using a variety of methods and materials. No matter what technique is used, though, a key element is the mold. One material often used for jewelry molds in this region is tufa (pronounced TOO-fa), the compressed fine-grain volcanic ash found in geological formations across the Navajo and Hopi reservations and in other parts of the arid Southwest. The best tufa stone for casting is soft enough to be cut into blocks with a hand saw and carved with blades or dental tools.

Native American silversmiths in the Southwest have been doing tufa casting since the 19th century, and cuttlefish casting for the past few decades. These are variations of what is known as gravity casting, or pour casting.

The basic technique is always the same: A jeweler prepares the inside surfaces of a two-part mold; carves a small channel, called a sprue, in the area that will be positioned upright for the pour; and binds the two pieces of the mold together. Using a high-heat torch, the jeweler then melts pieces of precious metal in a crucible, and pours the molten material through the sprue and into the mold.

If all goes as planned — if the temperature of the metal and the humidity in the air and the pattern of the mold and the consistency of the materials are all just right — the cast metal eventually can be cleaned and filed and shaped into the intended piece.

If something goes wrong — say the silver doesn’t flow all the way into the mold — it’s time for a Plan B. That would-be bracelet may become a pendant.

A Fickle Process

Ms. Cajero, 58, grew up in Santo Domingo Pueblo, between Albuquerque and Santa Fe. Even though both her parents were jewelers — her mother, Dorothy Tortalita, a silversmith and her father, Tony Tortalita, a lapidary artist — Ms. Cajero thought she lacked the patience needed to create jewelry and ended up working for the Indian Health Service. Then, in the mid-2000s, she started taking jewelry classes and discovered cuttlefish.

Despite its name, the cuttlefish is not actually a fish but a type of mollusk, and the cuttlebone is not actually a bone but the sea creature’s oblong internal structure that allows it to adjust its buoyancy. The soft surface of the dried cuttlebone has made it a medium for metal casting in many parts of the world for centuries. Ms. Cajero orders her supply online.

Cuttlebone is an ephemeral casting material. It is strong enough to take the heat — sterling silver has a melting point of 1,640 degrees Fahrenheit (893 Celsius) — but delicate enough for the surface to turn to ash after one pour. When hot metal hits it, cuttlebone gives off a smell like burning hair.

“But it creates such a beautiful texture,” Ms. Cajero said, “I can deal with the smell.”

In her work, cast pieces often become a backdrop for natural stones such as agates or jaspers. She recently made a cuff bracelet with flared edges, the textured silver accented with an undulating line of smooth, shiny sterling silver and a thumb-size green turquoise from the Grasshopper Mine in Nevada

She will often make a mold with cuttlebone on one side and tufa stone on the other, to create different textures, binding the pieces together with rubber strips cut from old bicycle inner tubes.

Casting can be fickle, so Ms. Cajero said that, just before each pour, she offers a quiet prayer that the process will be smooth and that the piece will connect with the right owner. “Each piece is prayed upon,” she said.

In the small room off her studio where she does casting and soldering, Ms. Cajero uses a propane/oxygen flame to melt pieces of sterling silver in a crucible. She includes a small amount of pure fine silver to give the metal a whitish sheen and make it a bit more malleable.

The melting and pouring process takes less than five minutes. After 10 to 15 minutes of cooling, it is time to check the results. “Each one is like a present. You get to unwrap it,” Ms. Cajero said. And as with any gift, she added with a smile, “sometimes it doesn’t turn out the way you anticipated.”

In this case, the silver had stopped short of one edge, leaving her with a smaller piece than she had anticipated.

“I’ll use it for something,” she said. “It’s not a problem.”

The Appeal of a Mystery

In fact, several jewelers said in interviews, the unpredictable nature of the casting process is part of the appeal.

“It’s a mystery every time,” said JT Willie, a third-generation Navajo jeweler and the chief executive of Navajo Arts and Crafts Enterprise, a business owned by the Navajo Nation and headquartered in Window Rock, Ariz.

Mr. Willie, 38, said he does different types of silver and bead work but turns to tufa casting when he wants to create a dense, textured piece of silver jewelry — such as the crescent-shape pendant, called a naja, that is the centerpiece of a classic squash blossom necklace.

Preparing for a pour can be an anxiety-inducing, fast-moving process. The tufa molds have to be preheated and the silver gets so hot, he said, it feels like it’s “ready to burn off your eyebrows.”

“I always think of lava when I’m pouring,” Mr. Willie said. Sometimes, he said, he will think the process didn’t go well, and yet “it becomes the best pour you’ve ever done.”

Connie Tsosie-Gaussoin, 74, a silversmith of Navajo/Diné and Picuris Pueblo heritage and the matriarch of a family of artists, said it is important to take cues from the work.

“The pieces talk to you,” she said, “and you just have to listen to them and be very fragile with them and just decide what they want to be, not what you want them to be.”

The Tufa Tradition

Much of the earliest tufa casting in the Southwest was done to turn silver coins into ingots that could be hammered into sheets or wire to make jewelry, according to Brian Fleetwood, who teaches jewelry making at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. But even when artisans started casting jewelry, they typically would grind off the texture to produce a smooth surface.

But around the middle of the 20th century — when Native American jewelers began to push traditional design boundaries, embrace new materials and develop individual styles — artists began to see more potential in the surface of tufa, Mr. Fleetwood said.

Depending on the quality of the stone and the detail of the design, a carved piece of tufa can be used anywhere from once to a few times. The material can be “idiosyncratic,” Mr. Fleetwood said, with seams and inclusions that make it difficult to handle.

But, he said, with skilled carving and the use of surface finishing techniques, it is possible to produce a silver surface with significant gradations of lights and darks, almost like a drawing. “You can create such visual depth in a very little space because of that tufa texture,” he said.

Artists who work with tufa often return to the same sources where their families have long found high-quality stone.

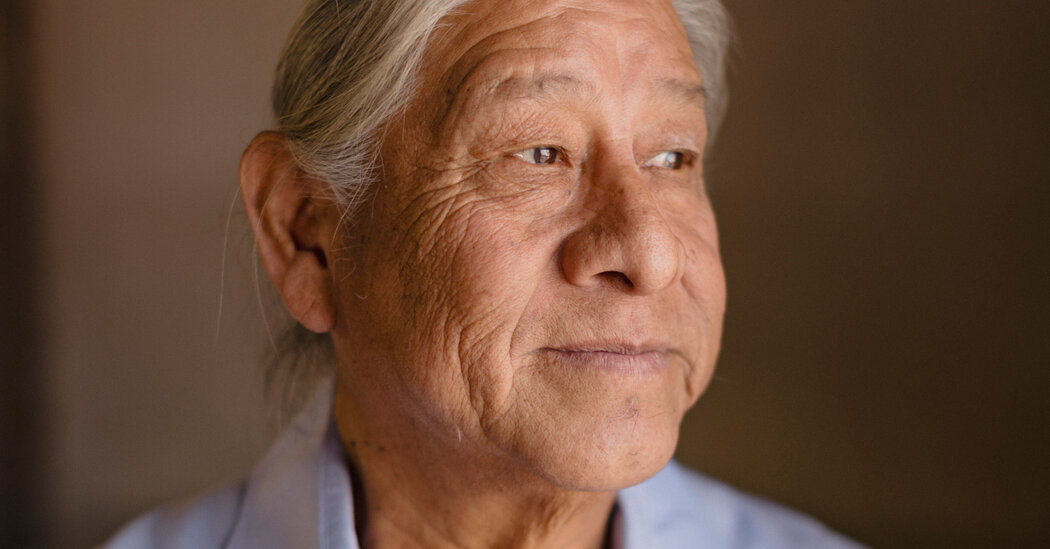

Anthony Lovato, 65, said he mines his supply at a remote spot in Northern Arizona where he first went with his maternal grandfather, Santiago Leo Coriz, more than 50 years ago. Mr. Coriz, a silversmith who died in 1997, had been getting tufa there for several decades.

Mr. Lovato, a fourth-generation jeweler, works alongside three of his sons and a grandson in what once was his grandfather’s home in Santo Domingo Pueblo (also called Kewa Pueblo). They work with blocks of tufa that, as he put it, have been sawed to about the size of Cracker Jack boxes, usually carving a design freehand into the tufa.

“We carve that negative design into the sandstone,” he said. “When we pour the silver from the top sprue opening, it becomes a positive image of our negative design.”

Working with a mirror image takes some time to master, according to Noah Pajarito, 22, who is Mr. Lovato’s youngest son and has his mother’s surname.

He said it was especially challenging to figure out how to carve his name into the back side of the mold. “When you write your name, you write it from right to left instead of left to right,” said Mr. Pajarito, who began carving tufa in middle school. “That was hard to learn, but my dad taught me well.”

Mr. Lovato often carves both interior sides of a tufa mold, aligning them carefully to create reversible necklaces and what he calls “spirit pendants” with designs from his Pueblo tradition, including petroglyphs and corn imagery. One wide necklace that he recently made featured a large turquoise from the Kingman mine in Arizona on one side and a red Brazilian agate on the other.

Earlier this year, Mr. Lovato was named a Living Treasure by the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, an annual program honoring Native American artists. (Ms. Cajero and her husband, the Jemez Pueblo sculptor Joe Cajero, were named in 2014; Ms. Tsosie-Gaussoin, in 2008.)

Sculptural Possibilities

Just as a painter may choose to work in oils or pastels, someone who does metal casting has a range of options available — not just tufa or cuttlebone, but other techniques such as lost-wax casting or sand casting.

Each method has its own aesthetic and appeal, but one draw for jewelers is the opportunity to work with metal in a three-dimensional way, said Henrietta Lidchi, executive director of the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian in Santa Fe and the author of “Surviving Desires: Making and Selling Native Jewellery in the American Southwest.”

“I think casting affords possibilities with three-dimensional expression which very few other techniques do,” she said in an interview. “It has this kind of capacity to be sculptural.”

Many Native American jewelers who do high-end work stick to single castings, and collectors tend to see such pieces not simply as luxury goods but as art, said Mr. Fleetwood of the Institute of American Indian Arts. “It’s not just bling. It’s work that has a story; it’s work that has perspective.”