One of the oldest items in my childhood home in Dallas is a yogurt culture. By my father’s estimate, it has been around for 25 years and seven months.

My dad started making yogurt when he and my mother immigrated to America from Delhi, India, in 1980. He has perpetuated the same culture — the bacteria that kick-start the fermentation process — ever since we moved from New Hampshire to Texas in 1992, by saving a bit of the previous batch of yogurt to create the next one.

He grew up eating homemade yogurt, and he makes it at least once a week, with no thermometers or special equipment. He brings a half-gallon of 2 percent milk to a gentle boil, and lets it cool down until it feels about as warm as a Jacuzzi, as he puts it. He vigorously mixes in a spoonful of the culture, then pours everything into a large stainless steel container. The yogurt sits in an unheated oven with the light on for a few hours until it sets, then he puts it in the refrigerator to chill.

I can’t recall a single day, growing up, when the fridge was without yogurt, or as it’s known in Hindi, dahi. We ate it alongside every meal, as a cooling respite to the spices in our dals and sabzis. Yogurt provided body and lift to my mother’s shrikhand, a sweetened cardamom-yogurt dessert, and the animating tang to her kadhi, a spiced soup made from chickpea flour.

There was never store-bought yogurt in our house, because none compared to my father’s velvety, tart homemade tufts. They looked like icebergs in your bowl, and made your cheeks pucker pleasantly. This yogurt tasted alive.

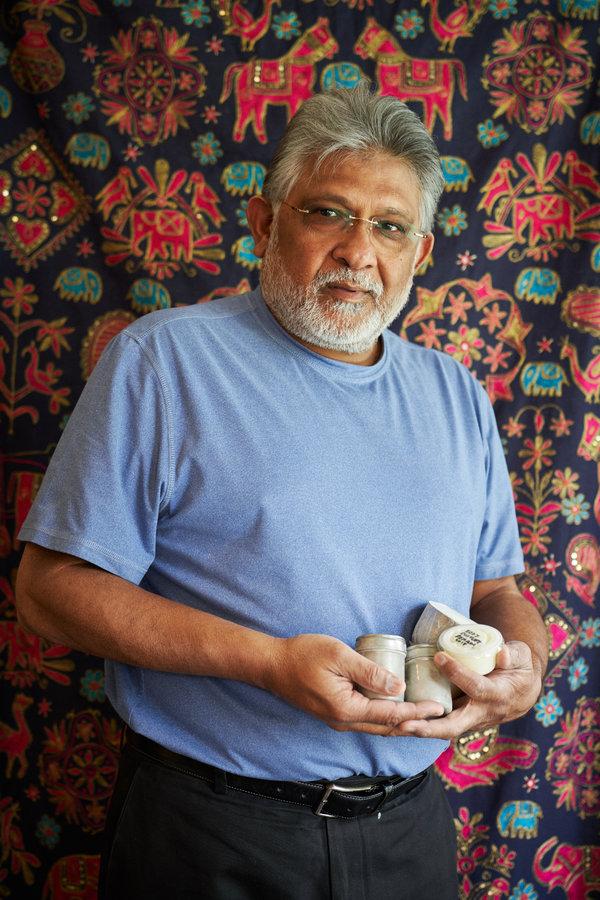

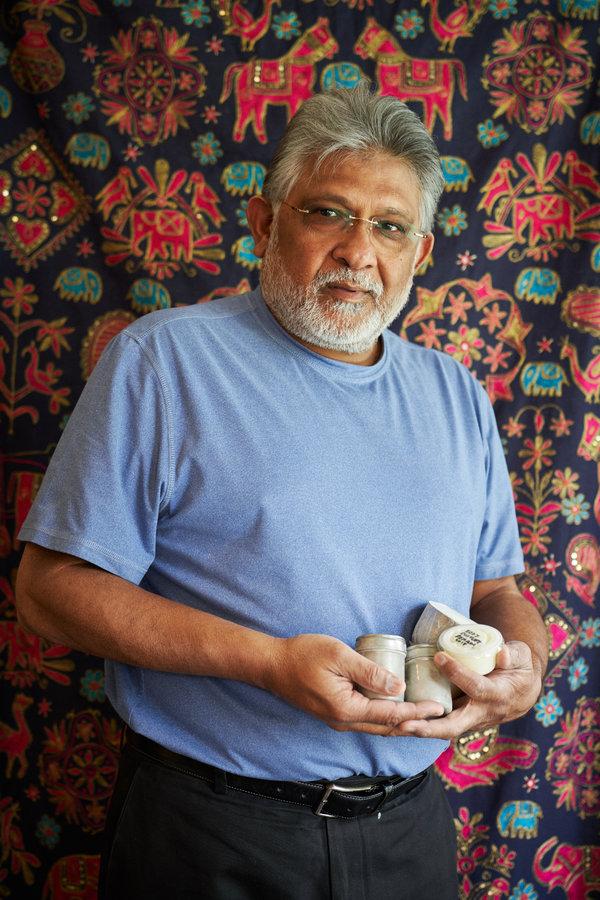

Shailendra Krishna, the author’s father, has kept his yogurt culture going for more than 25 years. CreditJonathan Zizzo for The New York Times

Yogurt is central to many of the world’s cuisines. But in South Asia, where geographical divisions run deep, it is one of the few ingredients that figure prominently in the cooking of nearly every region, from the subtle, vegetable-heavy foods of Gujarat in western India, to the light gravies and fragrant biryanis of Sindhi food in Pakistan.

The yogurt is typically made at home — a practice that’s economical and can produce large batches — and everyone has a special method: a particular brand of milk, a specific container, a warm corner of the house that is ideal for fermentation.

But for many South Asians who have emigrated, the most important element is the starter culture — the ingredient that not only gives each yogurt its unique, familiar flavor, but also allows yogurt makers to preserve and perpetuate their heritage across time and space.

Pooja Makhijani, 40, who works in communications for Princeton University, said her mother’s yogurt culture is “almost like the tracing of her journey.”

“The yogurt that will be served at dinner tonight was also here the day she landed in the United States” from Pune, southeast of Mumbai, in 1977, Ms. Makhijani said. “Her own narrative is encased in this.”

Families will go to great lengths to keep that narrative going.

Hetal Vasavada, the San Francisco author of the cookbook “Milk & Cardamom,” said that when her grandmother first came from Gujarat in 1991 to live with her family in Bloomfield, N.J., she tucked some yogurt from home into the folds of her sari blouse and sneaked it through customs.

Ms. Vasavada’s mother had done something similar when she arrived in 1986: She wrapped a tiny container of yogurt in carbon paper, believing that an airport X-ray machine couldn’t detect it. She got it through security, and the family is still using that culture.

Antara Sinha’s family (her parents are from Bihar, on India’s border with Nepal) moved around frequently in the United States. Ms. Sinha, 23, who lives in Birmingham, Ala., and is the social media editor for the website MyRecipes, had two pet turtles that she brought to each new home. Her parents’ constant was their yogurt culture.

“I remember we had the turtles on one side of the back seat, and then the yogurt culture in a bowl on the other side,” she said.

They had been given the culture by an Indian couple in Tyler, Tex., when they immigrated in 1994. “It is a community thing,” Ms. Sinha said. “A way of saying, ‘You are one of us, we will help you out.’”

My own family’s yogurt culture — which my father got from a sister-in-law, Sonia, who couldn’t recall where she procured it — has survived a move from one corner of Dallas to another, the two years my parents lived in the Philippines, and the many times my sister and I accidentally polished off a batch of yogurt without leaving any to make the next.

Luckily, my father, Shailendra Krishna, keeps two containers of emergency culture in the freezer — and has successfully used them a few times. (Arielle Johnson, a food scientist, confirmed that most bacteria can survive freezing.)

But accidents can happen. If you don’t keep your culture going, it can go bad.

Manisha Annam, 48, a Dallas real-estate agent who brought her culture to the United States from Pune in 2000, recently went on vacation for several weeks. When she came back, her yogurt had turned rancid. She had to revert to using a store-bought culture.

“I was so upset, you could not believe it,” she said. “Nobody in my family liked the taste. Everybody was complaining.” Eventually, she was able to borrow some culture from a friend.

Why go to all that trouble? Some people just like the consistent taste of yogurt made with their own culture.

“It is that full mouth feel,” Vivek Surti, 33, the managing partner at the Indian-inspired restaurant Tailor, in Nashville, said of his mother’s yogurt. (She was born in Gujarat.) “It is still sour, but it has this milky quality that coats all of your mouth. When you eat something spicy and you need relief, this is the yogurt that delivers that.”

Tailor serves yogurt made with his mother’s culture alongside dal bhat, or lentils with rice, and in a falooda-inspired panna cotta, with rose-flavored yogurt, vermicelli and strawberries, that will soon be added to the menu.

Arpita Mehta, 26, a brand strategist living in New Jersey, grew up eating homemade yogurt mixed with khichdi, a lentil and rice stew. The homemade version “had this richness that absorbs the khichdi,” she said. “The store-bought yogurt was a little bit watery. It just wasn’t as firm.”

The South Asian love affair with yogurt can be traced back to to 3500 B.C., when it was first consumed by the Indus Valley civilization, in what is now part of western India and Pakistan. But sometime between 1500 and 500 B.C., it became a staple food among the Vedic Aryans, pastoral people who raised buffalos and cows, said Pushpesh Pant, a historian and the author of “India: The Cookbook.”

Yogurt, which was probably discovered after milk had accidentally curdled, was a highly practical dairy product: It had a long shelf life; its cooling properties helped people tolerate warm climates; it could tenderize meat when used as a marinade; and it aided digestion.

Because of this, Mr. Pant said, yogurt was considered sacred and pure. In Hindu folklore and ancient poetry, yogurt is frequently mentioned. A spoonful of sweetened yogurt is considered good luck.

To many who enjoy it, it’s a cure-all. “If anything went wrong, I was given yogurt,” said Naz Deravian, 46, the Iranian-American author of the 2018 cookbook “Bottom of the Pot.” “Burns or cuts, hair growth, skin. My boyfriend broke up with me? Have some yogurt.”

Mr. Pant theorized that the thickness and tanginess of South Asian homemade yogurt result from the types of bacteria used. The strains in many Western yogurt brands are chosen to produce milder-tasting, more homogeneous curds. South Asian yogurt is typically made with a more acidic culture, the descendant of a yogurt that was originally created by curdling milk.

More important than the yogurt itself, a long-lived starter culture can become an heirloom, the physical representation of a lineage that can be passed on to future generations.

Sumayya Usmani, 46, a food writer in Glasgow whose family is from Karachi, Pakistan, said making yogurt from scratch “is the closest way that I feel the memories associated with my mom. Now I am teaching my daughter how to do it. It is a dying skill.”

Ms. Usmani has a point. Now that commercial yogurt is widely available at grocery stores, some younger people have no interest in continuing their families’ tradition, even if they feel sentimental about it. This is true for me: While I eat yogurt every day, I have made my father’s version only a few times. My refrigerator space is limited, and I travel often.

Chetna Makan, the author of the recently published cookbook “Chetna’s Healthy Indian” and a former contestant on “The Great British Bake Off,” said she gave up on making yogurt after her first attempt wouldn’t set because her home in Kent, England, was too cold.

She conceded that her store-bought yogurt was “bland, like a thick gloop,” unlike her mother’s, which she ate while growing up in Madhya Pradesh, in central India. But as a working parent, she would rather spend her limited time making other dishes from scratch.

For many who work in restaurants, however, tinkering with their family yogurt culture can hold a special appeal.

Ajesh Deshpande, 28, a line cook at Eleven Madison Park, in Manhattan, noticed that many of his colleagues had taken a keen interest in fermentation, particularly yogurt. He is thinking about bringing in his mother’s yogurt culture — it was brought to her 16 years ago by a friend from Rishikesh, in the Himalayan foothills — for his fellow cooks to experiment with.

“Wouldn’t that be cool?” he said proudly. “My mom’s old methods being used at one of the best restaurants in the world.”

Recipe: Easy Yogurt