It’s a warm morning, the sky is cloudless and the marshes of the Hoo Peninsula, 25 miles downriver from London, are thick with daises and red clover. In the churchyard of St Mary’s in the village of Lower Higham there is a scent of cut grass. The whole scene, in other words, is distinctly un-Dickensian.

But it is here, near the Thames estuary, that Charles Dickens’s 1861 novel “Great Expectations” opens: “Ours was the marsh country, down by the river, within, as the river wound, twenty miles of the sea.”

There’s no novel I love more, and I’ve come to know this peninsula well during the 15 years I’ve lived in London. There was a time, seven or eight years ago, when I would escape to this quiet landscape, weekend after weekend, as if looking for something I’d mislaid.

On this visit, having taken an early morning train to Lower Higham, a journey of no more than 80 minutes, my plan is to spend the day walking from St Mary’s, across the marshes to an isolated inlet named Egypt Bay, before returning via a second church, St James’s, in the village of Cooling.

Both churches have been proposed as the setting for the opening scene of “Great Expectations,” when the young boy Pip, visiting the graves of his parents and his brothers — “five little stone lozenges, each about a foot and a half long” — encounters the convict Magwitch, who has escaped from a nearby prison ship. (“‘Hold your noise!’ cried a terrible voice, as a man started up from among the graves at the side of the church porch. ‘Keep still, you little devil, or I’ll cut your throat!’”)

I’m carrying my favorite gazetteer, discovered in a book store in nearby Rochester on a previous foray: Colonel W. Laurence Gadd’s “The Great Expectations Country,” published in 1929 and long out of print. Colonel Gadd is forever “striking out,” in his rather upright way, but there’s a likable modesty to his guidance (“I make no claim to infallibility”) as we follow him from the Hoo Peninsula, via Rochester, to London, where the adult Pip is sent when he receives a fortune from an anonymous benefactor. But the colonel’s starting point, like the novel’s, is the marshes.

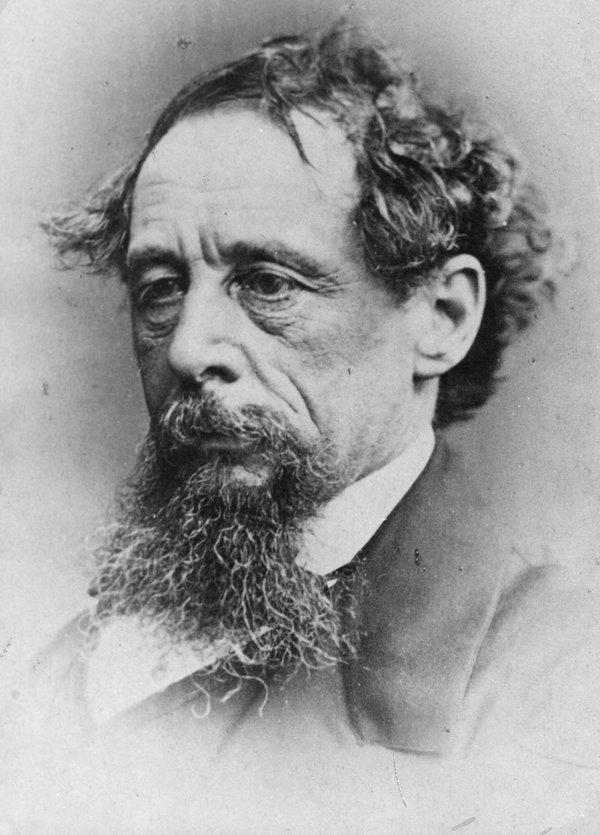

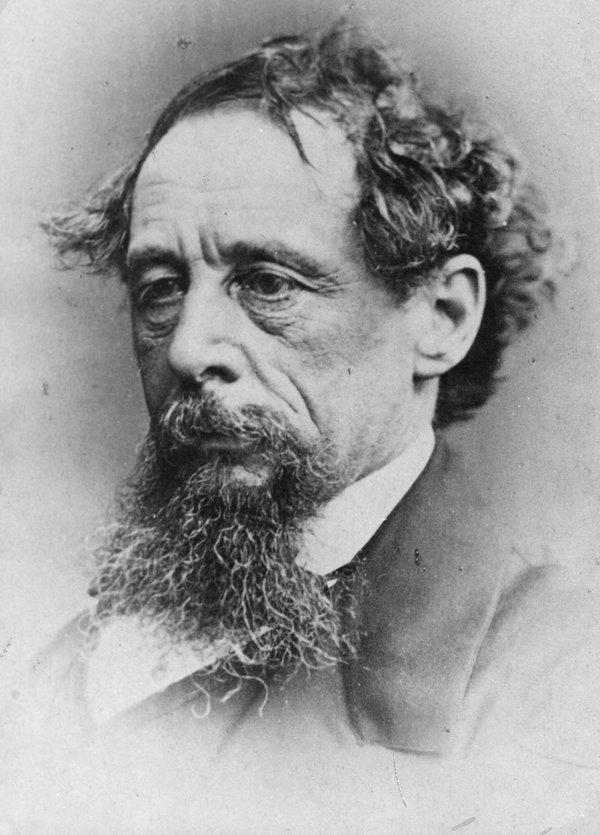

Charles DickensCreditHulton Archive/Getty Images

Both Sanctuary and Inspiration

The Hoo Peninsula divides the estuary of the Thames from that of the smaller Medway 10 miles to the east. To get a sense of its shape, take a seat on the churchyard bench and rest your right foot on your left knee: the Thames follows the curve of your heel and sole; the Medway the bony top of your foot. Both rivers open to the North Sea beyond your toes. The marshes occupy most of the northwest of the peninsula, which is to say your heel.

A foot is apt for a place that offers such stimulating walking, but the terrain is not without its challenges. If you look at a UK Ordnance Survey map, you can see how wet it is: not only bounded by the two rivers and their mud flats, it’s veined by hundreds of ditches, streams, dikes, fleets and runnels, most of which can only be crossed using infrequent footbridges.

If it is a formative realm for Pip, the peninsula can also be seen as central to Dickens’s own world — a rural counterpoint to London: at once his sanctuary and his inspiration. As a child, Dickens lived in the naval port of Chatham, on the Medway four miles to the southeast, and in later life, as a world-famous author, bought a home near Lower Higham, Gads Hill Place, where “Great Expectations” was written and from where he would take regular walks on the marshes. (Today the building forms part of a private school, though there are plans to open it to the public.)

St Mary’s, two miles north, was his local church, where his daughter Katey was married in 1860. In “The Great Expectations Country,” Colonel Gadd maintains that the church in the novel must be this one, since its architecture matches that described by Pip.

“All the other churches in the peninsula,” he writes, “have square stone towers, but [St Mary’s] has a quaint timber steeple, shingled with tiles. Pip saw this steeple under his feet when the convict tilted him backwards on the gravestone.”

For Pip, the church is where life gives way to death, but also where the peopled world cedes to the marshes — “a dark flat wilderness beyond the churchyard, intersected with dikes and mounds and gates, with scattered cattle feeding on it.”

“The Great Expectations Country” in hand, I strike out.

The Thames Estuary on the Hoo Peninsula, where Charles Dickens would take regular walks on the marshes.CreditTom Jamieson for The New York Times

Afternoons by the Thames

Marshland is born of rivers: as silt is sluiced down from the land to the sea, the tides in turn lift it back onto the land. First there are the mud flats, covered daily by the tides. As silt accumulates on them, the mud flats rise until they stand clear of the sea for long enough to become colonized by salt-loving plants. Then they become salt marsh, the Thames estuary’s richest habitat. When the salt marsh is drained and walled off from the tide it becomes grassland.

In a field half a mile north of St Mary’s, I wait at a railway spur for a freight train to shunt slowly by. It’s bound for London, the driver yells from his window, carrying estuary sand from the Cliffe aggregate works.

Once the train has passed, I follow the footpath over the railway and through the works with its churning conveyor belts and towering sand dunes. In “Great Expectations,” the adult Pip remembers fondly the summer afternoons he spent with his beloved Uncle Joe, the blacksmith who is the closest thing he has to a father, lounging beside the Thames at “that old battery over yonder.” It is there, too, that Magwitch bids the boy to meet him, with a file and “wittles” (food), the day after their first encounter.

Close to the former site of the battery, fenced off, flooded, and ringed by brambles, you can see the monolithic, derelict Cliffe Fort, sitting on the peninsula’s heel like a wart. Built in 1870, less than 10 years after the publication of “Great Expectations,” to counter the threat of French invasion, it is one of the Thames’s oldest remaining defensive fortifications.

A narrow footpath path runs along an embankment between it and the river’s exposed mud flats, which are littered with detritus washed down from the city — plastic bottles, wooden pallets, plastic ship’s fenders, deflated soccer-balls, shoes. The black hull-ribs of ships scuttled long ago reach out of the mud. Gulls squabble noisily.

It’s not a pretty place, or a friendly one, so it’s a relief when the footpath opens out onto the marshes. As the grinding and banging of the aggregate works are left behind, a cooling wind rises from the sea. Even in the sunshine, with the giant container ships plying the Thames, this is recognizably Pip’s marsh country: flat, treeless, glinting with ribbons of water — a halfway place that is marine as much as terrestrial.

The embankment follows the Thames’s high-water line and will take me all the way to Egypt Bay, with the river on my left and the marshes on my right. “If you like solitude, and fresh air, and open spaces,” writes Colonel Gadd, “the trip is worthwhile.”

The embankment was built in the 1880s to prevent the Thames from flooding the marshes during storms and high tides. It transformed life on the peninsula. As late as 1874, Her Majesty’s Inspector for Schools described the area as “low-lying, aguish, and unhealthy, where no one would live if they could help it.”

Egypt Bay on the Hoo Peninsula. “If you like solitude, and fresh air, and open spaces, the trip is worthwhile,” wrote the author of “The Great Expectations Country.” CreditTom Jamieson for The New York Times

The “ague” — malaria — had been one of the chief perils of living here; the marshes, Pip tells Magwitch, are “dreadful aguish.” When the embankment was built, standing floodwater where malaria-carrying mosquitoes bred was prevented and the disease largely eradicated.

As the Thames widens toward the sea, the towering robotic cranes of the London Gateway container terminal dominate the river’s far bank a mile north, but to the south the marshes are at their most exposed and expansive. Looking across them toward Northward Hill, two miles away, I feel my city eyes widening, adjusting to the open space.

The environmentalist Wallace Stegner wrote in 1960 that we need “wild country available to us, even if we never do more than drive to its edge and look in.” It may be hard to think of this landscape so heavily shaped by humankind as wild, but to know that it is here, just an hour or two from London, still intractable and sparsely populated 180 years after Dickens — it’s a source of comfort.

A village ‘as unhealthy as it is unpleasant’

“The distance from Cliffe Creek to Egypt Bay is about three miles,” Colonel Gadd announces. It takes him an hour, “as the way is for the most part on slippery mud.” The embankment path avoids the mud, but is more like six miles, and it’s past 4 p.m. by the time I reach Egypt Bay. I arrive sunburned and windblown, my lips taut and salty.

The provenance of the bay’s name is unclear, though it has been suggested it’s because a Phoenician coin was unearthed nearby. What is known is that this sandy inlet was an ancient landing place, and favored by smugglers in the 19th century. Beyond the mudflats, says Colonel Gadd, is where the prison hulk was from which Magwitch escaped before apprehending Pip — “in the topographic sense,” at least, for the vessel once anchored here was not a prison hulk, the colonel concedes, but a Coast Guard lookout.

I rest on the sea wall and when I stand, a group of swans rises from a nearby dyke, five of them, passing over the marshes until they are no more than gleaming dashes against the dark woods of Northward Hill. Turning away from the river, I follow them south across the marsh, locating the wooden footbridges that cross the drainage ditches, and finally heading west, until the square stone steeple of St James’s Church comes into view.

According to the historian Edward Hasted, writing in the 1770s, Cooling was “an unfrequented place, the roads of which are deep and miry, and it is as unhealthy as it is unpleasant.” On this late summer’s afternoon the village has an air of tranquil prosperity, and is so still and unpeopled as to feel like a film set. I don’t see a soul.

“Close by the south porch,” Gadd writes of the church, ‘are the gravestones of Pip’s little brothers.’ A meter in length and torpedo-shaped, the real gravestones — thirteen in total — belong to two branches of the Comport family, victims of malaria in the late 18th century. In Dickens’s novel there are just five, but as his friend and biographer John Forster put it: “with the reserves always necessary in copying nature not to overstep her modesty by copying too closely, he makes the number that appalled little Pip not more than half the reality.” No reader would believe thirteen.

Colonel Gadd insists that the stones were imaginatively “imported” by Dickens to St Luke’s at Lower Higham, where my walk began. But for me it is St James’s, because of their presence, that will always be where Pip met Magwitch on that “memorable raw afternoon towards evening.”

Even today, in the warm raking light, I suppress a small shudder. A place might inspire fiction, but fiction in turn can shade your experience of that place.

I remember my first reading of the novel, long before I set foot here. It was Pip who knew these “death-cold flats,” but that terrifying stranger who would transform his life — part magus, part witch — seemed to be the very marshes incarnate, a shackled golem formed of salt-mud and fog. (“Keep still, you little devil, or I’ll cut your throat!”)

Once I’ve written my name in the church’s visitor book, I return “The Great Expectations Country” to my backpack, and start the four-mile walk back to Lower Higham and my train to London.

William Atkins is the author of “The Immeasurable World: Journeys in Desert Places” (Doubleday).

Follow NY Times Travel on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Get weekly updates from our Travel Dispatch newsletter, with tips on traveling smarter, destination coverage and photos from all over the world.