IN THE PHOTOGRAPH, 16 raw yolks sit in a plastic ice-cube tray, each compartment brimming with albumen. Around the tray lie broken eggshells, cast off on a dimensionless blue surface. As a composition, it’s simple and striking, with saturated Jolly Rancher colors, the kind of image that pops on Instagram. But it doesn’t tell the story we’ve come to expect from food photographs that dominate social media: There’s no teasing promise of deliciousness or even edibility. The yolks are sunshine-yellow yet eerily rectangular, filling their ice-cube cells, which reflect the dimensions of the photograph itself. Nature has given way to artifice; shell has been separated from yolk, form from content, food from function. There’s nothing to eat here.

The duo behind the image, Josie Keefe and Phyllis Ma, both 31, have made photographs, zines and stop-motion videos together since 2014 under the name Lazy Mom — an invocation of the cultural boogeyman of the “bad mother” who neglects her children. Instead of assembling a proper after-school snack, Lazy Mom indulges artistic impulses, taking close-ups of a smushed mustard packet or a pane of Wonder Bread immured in Ziploc, the light catching on plastic creases with a Vermeer-like luster. In working with food — which means playing with it, something “we’re told not to do,” Keefe says — the women are among a cohort of American artists for whom food is both material and subject matter, carrying on a tradition that reaches back centuries but has expanded in range and theme dramatically in the past few decades.

Their forebears include the Swiss provocateur Dieter Roth, who printed his 1968 poetry journals on bags filled with sauerkraut, lamb or vanilla pudding (the last spiked with urine), and the British sculptor Antony Gormley, whose 1980-81 “Bed,” built of 600 loaves of bread, featured depressions as if left by sleeping bodies. In 1991, during the Persian Gulf war, the Cuban-American artist Félix González-Torres spilled gray licorice candies on a gallery floor, invoking a fallen hail of bullets. Food has also been long exploited for surrealist sight gags, as in the British artist Sarah Lucas’s 1997 “Chicken Knickers,” in which she posed with a whole raw chicken, disemboweled and strapped to the front of her underpants. Elsewhere, it’s been rendered unrecognizable: In the American artist Dan Colen’s early 21st-century canvases, chewing gum supplants paint; and for 2009’s “Cola Project,” the Chinese conceptual artist He Xiangyu boiled down 127 tons of Coca-Cola into an oil-dark residue that he used as ink to emulate paintings from the medieval Song dynasty — a product of the industrial West transmuted into an emblem of old China.

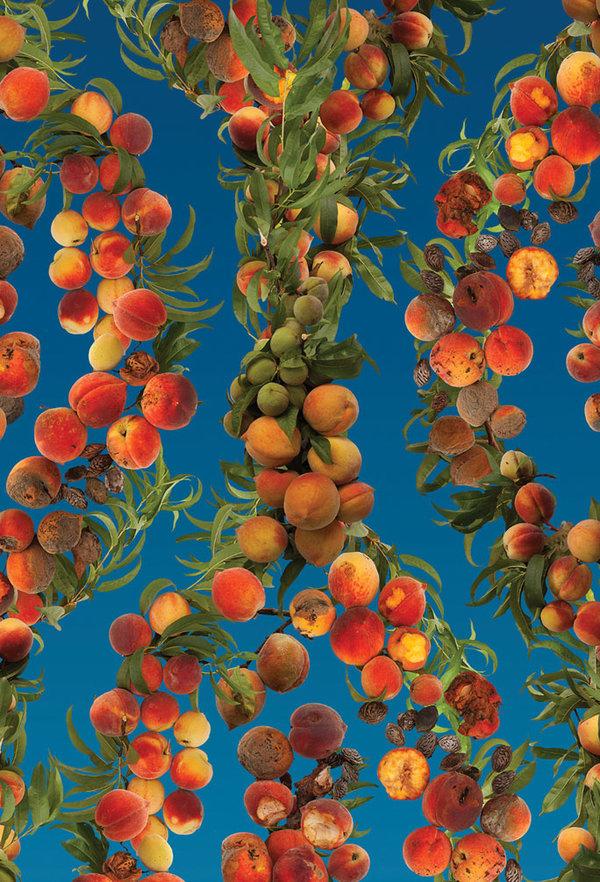

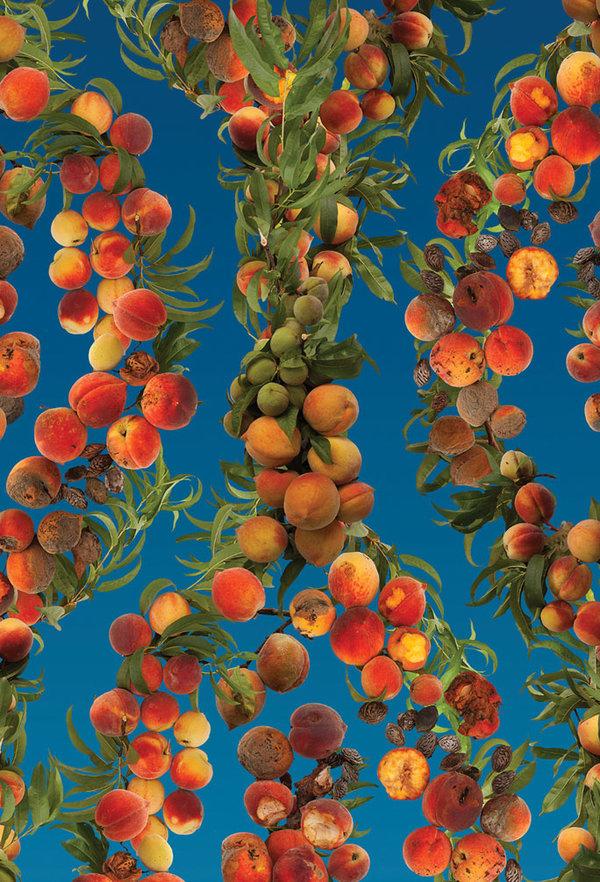

Fallen Fruit’s “A Portrait of Atlanta” wallpaper (2013), a compositeof photographs of orchards throughout Georgia.CreditFallen Fruit (David Allen Burns and Austin Young), “Peach Wallpaper Pattern/A portrait of Atlanta,” 2013, from the exhibition “The Fruit Doesn’t Fall Far From the Tree,” commissioned by the Atlanta Contemporary

What’s different for the artists emerging today is that their work is born out of, and must on some level contend with, a culture that has turned food into fetish. In the disembodied world of social media, food is appreciated as an almost exclusively visual medium, enshrined in hyper-processed, highly mannered photos without true corollaries in the physical world. It exists in a kind of suspended state of imagined deliciousness, never to be actually tasted by most viewers: a totem of eternally unconsummated desire. This is a perspective of extraordinary privilege, to be so secure in our food supply that we see food not as a requirement for biological survival but as entertainment — encouraging a strain of frivolity of which Keefe and Ma are wary. (According to a United Nations report, an estimated 821 million people around the world suffered from undernourishment last year.)

Part of Lazy Mom’s mission is to mock the preciousness of modern food culture, the alienating perfection of food styling and professionals “who tweezer everything on the plate,” Keefe says. Nevertheless, their satirical images draw some of the same audience as more straightforwardly celebratory Instagram feeds, and they’ve been hired to style food for the Ace Hotel and the now-defunct culinary magazine Lucky Peach. The quandary for Lazy Mom and their peers is how to subvert and interrogate society’s thraldom to food without being swallowed up by it.

LONG BEFORE IT became a source of irony, food was a figurative object in still lifes, which were never so popular as in Europe’s Low Countries in the early modern age. Critics initially disdained the genre as merely decorative, lacking the moral heft of narrative art. But food has always had a story: It is ephemeral — destined to be consumed or spoiled — and thus, in a subgenre of still lifes called vanitas, a reminder of mortality. And food has cultural freight, helping to define social strata. As Amsterdam prospered from trade in the first half of the 17th century, Dutch still lifes morphed into luxurious mise-en-scènes featuring lemons from the Mediterranean and mince pies suffused with Indian spices. These were as meticulously staged as today’s Instagram posts, forgoing realism to make a statement about the increasingly rich, bourgeois merchants who had commissioned them.

That idea — food as a signifier of status and wealth — still holds today. In “Palate” (2012), the Greek-born American artist Gina Beavers transforms snapshots of food found online — glistening oysters, a pileup of chicken and waffles — into relief paintings with messy surfaces of smacked-around acrylic paint, thickened and contoured by pumice and glass beads. The resulting image-objects are stylized to the opposite extreme of glossy social media, overaccentuating the pockmarks, ooze and fleshiness of reality. In 2015, the Canadian artist Chloe Wise slapped Chanel and Prada logos on purses made out of what looked like bagels, challah and jam-smeared toast. Like the designer accessories they parodied, they too became coveted commodities — although the fact that the “bread” was molded out of urethane, not dough, took away some of the fun.

In Images: Artists Who Play With Their Food

14 Photos

View Slide Show ›

As a material, food brings a unique texture and sensuality to works that may not explicitly address food qua food, like the American sculptor Andy Yoder’s executive wingtips in shining licorice from 2003, or the French-Algerian artist Kader Attia’s 2009 scale model of the ancient fortified town Ghardaia in the Saharan M’zab Valley, constructed out of couscous that evoked sand. (Conservators were requested not to rebuild it if it crumbled.) Key to these works is the speed of their degradation: Rot is not only inevitable — it’s the goal, as in the Swiss artist Urs Fischer’s “Faules Fundament (Rotten Foundation)!” (1998), in which brick walls rise from a base of decaying fruit. At times, the instability of such art can alarm and even threaten. Rotting fish, festooned with sequins and beads, gave off such an overpowering scent at the Museum of Modern Art’s 1997 showing of the South Korean artist Lee Bul’s “Majestic Splendor” that they had to be removed from the Manhattan museum; earlier this year, a new iteration, doused with potassium permanganate to neutralize the smell, caused a small fire at a gallery in London.

It’s vanitas once more, pointing to the transience of life and the ultimate degradation of all earthly value, an idea that Fischer pushed into the realm of farce with his 2015 exhibition of ripe fruit set in a pristine toilet bowl, both cornucopia and rude reminder of the endpoint of digestion. The act of using such impermanent materials is both a confrontation with and uneasy embrace of what awaits us. From 1992 to 1997, the American artist Zoe Leonard stitched fruit peels back together, as if trying to repair the original fruit, in memory of her friend the artist David Wojnarowicz, who died of complications from AIDS in 1992. On display, the skins lie as if dropped and forgotten on the floor, a still life made manifest: life stilled, waiting to turn to dust. Leonard has insisted that they be allowed to disintegrate.

For other artists, consuming the materials before they rot is essential to the practice. When Gormley made his bread bed, he didn’t cut the shape of his body out of the loaves — he used his teeth. (“I ate my own volume in bread,” he wrote.) In 1992, the American artist Janine Antoni exhibited two 600-pound cubes, one of chocolate, one of lard, both of which she had gnawed; the bitten-off material became lard lipsticks and chocolate hearts. Sometimes viewers are encouraged to eat the art, as with the rainbow heap of brightly wrapped Fruit Flasher candies that González-Torres arranged in 1991 as memorial to — and, at 175 pounds, incarnation of — his partner, who died of an AIDS-related illness earlier that year.

Jen Monroe’s “Untitled” (2018), photographed by Corey Olsen, assembled using leeks, cauliflower, cucumber, star fruit, agar, milk, grapes, lime, tapioca and endive.CreditJen Monroe, “Untitled,” 2018. Photograph: Corey Olsen

Feeding the audience can be an act of generosity. In the early 1990s, the Argentine-born Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija converted galleries into kitchens, where he cooked pad thai or curry, which visitors ate for free; the curry (and its price) lives on at Unclebrother, the seasonal restaurant in the Catskills that he owns with his gallerist Gavin Brown. At the same time, this interaction turns the viewer into both an object and subject of the work — a complicity perhaps most fraught when artists offer complete sit-down meals, blurring the line between dinner party and performance. In 1971, the New York artists Gordon Matta-Clark, Carol Goodden and Tina Girouard opened Food, a restaurant-slash-installation in SoHo where eminences like Donald Judd and Robert Rauschenberg reportedly served as guest chefs. One evening’s menu focused entirely on bones, which were afterward scrubbed and strung together for diners to wear. In the same era, the Romanian-born Swiss artist Daniel Spoerri ran a restaurant in Düsseldorf where occasionally, at the end of the evening, dinner remains would be transfigured into what Spoerri called a tableau-piège, the tabletop and all its contents (sticky plates, half-empty glasses) mounted on the wall. His idea — that “the horizontal becomes vertical” — foreshadowed the overhead food shots that are now the universal language of Instagram.

AMONG OTHER CONTEMPORARY artists, it’s often the party — not the dinner itself — that influences the work. In 2015, the American artist Jen Monroe, 29, began hosting monochromatic meals in Brooklyn, inspired by the all-black party in the French writer Joris-Karl Huysmans’s 1884 novel of debauchery, “À Rebours,” and the Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s 1932 “The Futurist Cookbook,” in which the recipes include instructions for diners to take bites while simultaneously stroking sandpaper and being sprayed with carnation perfume. (The French artist Sophie Calle did a similar series of monochromatic meals in 1997, but they were solo affairs, shared with the public only in photographs.) Wanting to upend restaurant conventions with food that is delicious but also disturbing, Monroe has served briny shrimp mousse in Barbie-pink, beet-stained deviled eggs, lurid yellow sushi in pillboxes and strawberries already bitten into (through plastic wrap, as a sanitary measure).

The New York City-based conceptualist Laila Gohar’s work is less overtly confrontational but still destabilizing. Now 30, she started out cooking homey dishes for friends; by 2013, she found herself suddenly in demand as a caterer, a career she never sought. (She had been working as a journalist.) Over time, her food has veered toward the avant-garde, with diners invited to pluck marshmallows from a six-foot-tall mountain, uproot mushrooms growing in elegant white pots and snip pieces of dehydrated fruit leathers hanging in translucent sheets from towel rods. The ephemerality of her installations, which take months to research but hours for guests to destroy, pleases her; she’s skeptical of the artist’s need to “leave a mark.” Still, when she creates events for brands like Tiffany & Company, Shiseido and, yes, Instagram, she’s concerned that she’s contributing to the proliferation of interactive food experiences that favor a manufactured “moment” over contemplation. Everything she makes is meant to be tasted, not simply commemorated in a photograph: “It’s important to me that the food is not used in vain,” she says.

For David Burns and Austin Young, American artists behind the Los Angeles-based collective Fallen Fruit, which was founded in 2004 (with Matias Viegener), food affords an opportunity to forge a social connection. “Fruit is one of the most democratic materials,” Burns says. He and Young, 48 and 52 respectively, walk through cities and map fruit trees on or hanging over public property, identifying them as a common resource. They plant trees as well — to get funding, they’ve occasionally had to argue that the trees are sculptures that just happen to be alive — and organize fruit-foraging expeditions. Their parks have rules of engagement: “Go by foot, say hi to strangers, take what you need and leave the rest,” Burns says. In their work, which includes fruit-printed wallpaper, prints and installations, aesthetics are inseparable from civics. “Public spaces are almost designed out of fear,” Young says. “We’re doing this because we trust people.”

Food is, fundamentally, a necessity, and feeding others is a social compact: The 41-year-old American artist Dana Sherwood has been exploring these ideas since 2010 by baking elaborate layer cakes for animals. Her subjects include mice eating their way out of an elaborate pastry replica of the New York Stock Exchange and raccoons, possums and stray cats happening upon a table set at night in a Florida backyard, their feral devourings captured on video by infrared cameras. Her basic recipe comes from a 1970s cookbook, incorporating ingredients traditional to animal diets — seeds, grapes, chicken hearts — although she finds that her diners often prefer frosting. (“No one’s ever eaten the kale,” she says.) The work relies on the animals’ unpredictability — “I found that it got better when I stopped trying to control the outcome,” she adds — and natural instinct: They eat the food not because it’s pretty but because they’re hungry.

And with hunger comes fulfillment, food restored to its natural function. After Sherwood’s nocturnal feasts, there’s no waste. In the morning, the tablecloth is stiff with sugar, and birds fly down to peck the crumbs.