Did the people who brought you baby powder and baby shampoo also bring you the opioid crisis?

That will be the question before an Oklahoma judge starting Tuesday, as the first civil trial takes off on the long, nationwide runway of trials against prescription opioid manufacturers, distributors and sellers. Oklahoma is squaring off against Johnson & Johnson, the New Jersey-based, family-friendly giant, which produces a fentanyl patch.

On Sunday, another defendant in the case, Teva Pharmaceuticals Ltd., the Israel-based producer of generic medicines, including opioids, settled with Oklahoma for $85 million. Details of how the state will allocate the money have not yet been finalized.

In a statement, the company said, “The settlement does not establish any wrongdoing on the part of the company; Teva has not contributed to the abuse of opioids in Oklahoma in any way.”

There is great interest in the case, which originally included Purdue Pharma, and not only from lawyers in nearly 1,900 federal and state lawsuits who want to see how the evidence and legal strategies resonate.

“So much of the litigation has remained under seal or redacted that this will be the public’s first glimpse into Pandora’s box,” said Elizabeth C. Burch, a law professor at the University of Georgia who writes about mass torts. “Not only will a trial occur, but it will be televised.”

While the state has not said how much it is seeking, the Oklahoma attorney general, Mike Hunter, has said that companies have caused opioid-related damages worth billions of dollars. But Purdue Pharma already settled with the state in March for $270 million. With the company that has become embedded in the public’s mind as an arch villain gone from the proceedings and Teva also out of the case, will Mr. Hunter be able to stick J & J with the rest of the bill?

Oklahoma, a largely rural state whose medical, social welfare and criminal justice systems have been ravaged by opioid addictions and deaths, has “home court advantage,” Ms. Burch said.

But the case is hardly a slam-dunk.

The challenge in all opioid cases is how to closely tie each defendant to the carnage.

In its attempt to frame that narrative, Oklahoma is relying on just one legal theory, which itself has an uneven record.

The theory — that J & J violated public nuisance law — is also being raised in the first federal cases to go to trial in Cleveland, Ohio, currently set for Oct. 21. All eyes will look to the Oklahoma trial as an out-of-town rehearsal for that big show. How will witnesses perform? Which arguments will resonate?

“If J & J prevails in Oklahoma, they may feel they are gaining leverage” in the federal negotiations, said Alexandra D. Lahav, a professor at the University of Connecticut School of Law who is an expert on bellwether trials.

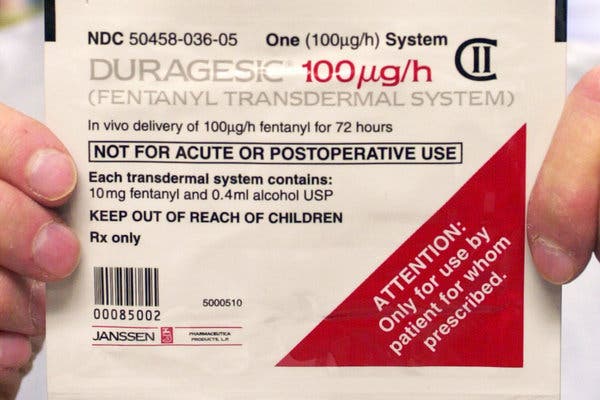

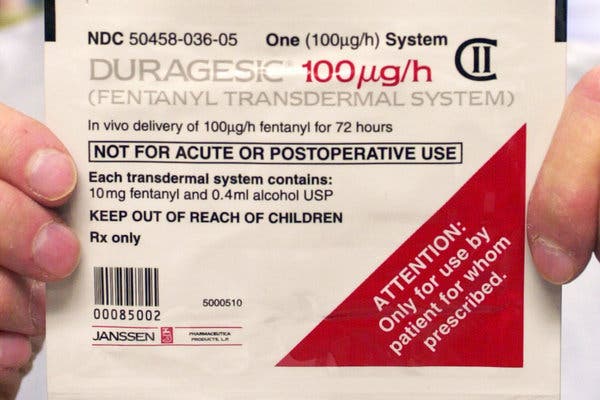

Through its pharmaceutical division, Janssen, J & J manufactured Nucynta, an opioid tablet, which it divested in 2015. It still makes Duragesic, a fentanyl patch. Teva produces Actiq and Fentora, for breakthrough cancer pain.

Through a company spokesman, J & J said that since 2008, its opioid medications have amounted annually to less than 1 percent of the opioid prescriptions written nationally. A Teva spokeswoman said its medications were administered infrequently in Oklahoma: Between 2007 and 2017, she said, the state reimbursed just 245 Actiq and Fentora prescriptions.

CreditDan Loh/Associated Press

The case is a bench trial, heard before Judge Thad Balkman without a jury, but media attention and courtroom cameras will essentially render the public into a collective jury.

Publicity heightens pressure. The case already has a political shadow: Not only is Mr. Hunter an elected official, but Judge Balkman, a former state legislator, is also elected.

J & J also has reason to be wary of the spotlight: It wants to protect its family-friendly branding. In redacted court documents, Oklahoma has accused J & J of targeting patient groups for opioid sales, including veterans, older adults and children.

In a statement, John Sparks, a lawyer for J & J and Janssen, said, “Janssen did not market opioids to children, and the State’s suggestion to the contrary is false and reckless.” Instead, he continued, Janssen had designed a drug-abuse prevention program with a school nurse association.

J & J, with 2018 sales of $81.6 billion, is already waging a public-relations campaign as it continues to fight lawsuits alleging that its talc-based baby powder caused cancer in some consumers.

If Oklahoma is not ground zero for the emergency, it’s “certainly close,” Mr. Hunter said recently during a panel on opioids at the Bipartisan Policy Center in Washington. Between 2015 and 2018, he said, there were 18 million opioid prescriptions written in a state with a population of 3.9 million. In a 15-year period, overdose deaths increased 91 percent.

In briefs, lawyers for Mr. Hunter who, like many government officials bringing such cases, is using outside counsel, have called J & J the “kingpin behind the public-health emergency.”

One of Mr. Hunter’s lead lawyers lost a niece to opioids; another, a son.

Oklahoma’s case against J & J largely falls into three areas. The first is the company’s marketing and sales practices, including targeting populations like veterans and children, and using patient front groups and high-profile doctors who oversold the benefits and downplayed the risks of the drugs. By doing so, the state says, the company helped normalize opioids from what had originally been a very conservative approach to them.

The second is J & J’s former ownership of two companies that produced and refined Tasmanian poppies into narcotics material for other drug manufacturers, including Purdue. Finally, the state points to the company’s development and sales of its own opioids.

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

J & J says the company manufactured drugs that played only a minor role in the market, even as it was conducting business that was heavily regulated and approved by government agencies.

The company stopped marketing Duragesic by 2008, court papers said, and divested Nucynta in 2015, the year the company ceased marketing opioid medication altogether.

J & J’s Mr. Sparks said that Oklahoma “attempts to group all manufacturers together with general and broad allegations.”

In 2017, Oklahoma became one of the first states to file a prescription opioid lawsuit. In the ensuing months, the case has morphed considerably.

Oklahoma recently jettisoned most of its claims to concentrate on just one — that the companies violated the state’s public nuisance law, creating a substantial health harm.

Unlike a conventional lawsuit that seeks compensation for damages already incurred, the state is asking J & J to pay to “abate” the nuisance it is accused of creating, going forward.

Public nuisance laws, which are centuries old, were invoked when something interfered with a right common to the general public, traditionally roads, waterways or public spaces. Recently, their use has been expanding, with mixed results: success for the Big Tobacco settlement and some pollution cases; failure in gun litigation and most lead paint cases.

Ms. Burch said some courts have found that those manufacturers didn’t have a specific duty to the public. The companies had prevailed by arguing that once the product left their facilities, they were not the direct cause of the ensuing harm or in a position to remedy it.

Similarly, she said, opioid defendants contend that the connection between manufacturers and overdose deaths is too attenuated.

Earlier this month, a North Dakota judge dismissed that state’s case against Purdue, including its public nuisance claim. While the ruling affects only that state, lawyers have said the decision creates an appellate template for defendants. Public nuisance laws, the judge wrote, were not intended where “one party has sold to another a product that later is alleged to constitute a nuisance.”

Mr. Hunter says that Oklahoma’s own law is “powerful and expansive.”

The state had been eager for a jury trial. But recently, lawyers reversed course and requested a bench trial, despite the perception that a jury could be readily convinced to seek revenge for the opioid devastation.

That perception is not necessarily true. “Juries are increasingly pro-defendant,” said Ms. Lahav. “And the state may feel that Oklahomans are business-friendly and individualistic.”

Jurors might have responded well to the company’s argument that manufacturers were producing medicines that were government-approved, she added, and that people had a choice about whether or not to take them.

It was J & J who wound up requesting a jury trial. That was likely because, said Adam Zimmerman, who teaches complex litigation at Loyola Law School Los Angeles, Judge Balkman has made rulings against the defense and has steadily marched the parties toward a trial date.

“J & J would probably rather try their luck with 12 people as opposed to this one person,” he said.

In a statement about the Teva settlement, Mr. Hunter said: “Nearly all Oklahomans have been negatively impacted by this deadly crisis and we look forward to Tuesday, where we will prove our case against Johnson & Johnson and its subsidiaries.”