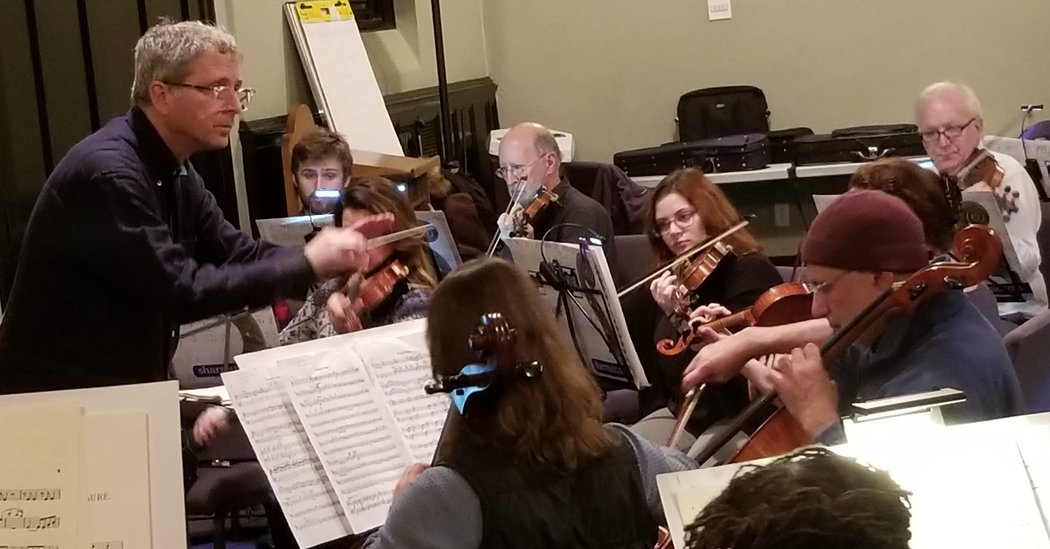

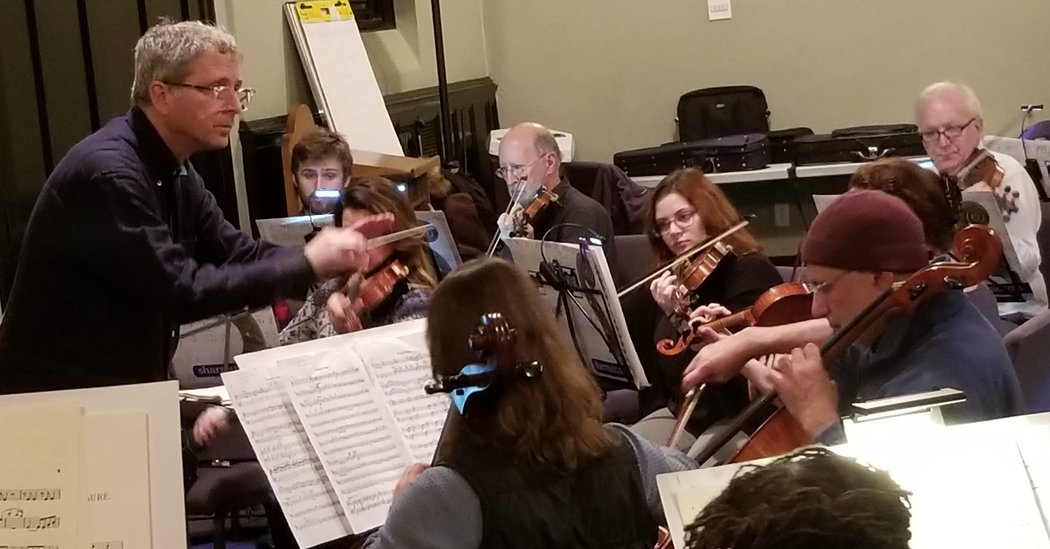

When Ronald Braunstein conducts an orchestra, there’s no sign of his bipolar disorder. He’s confident and happy.

Music isn’t his only medicine, but its healing power is potent. Scientific research has shown that music helps fight depression, lower blood pressure and reduce pain.

The National Institutes of Health has a partnership with the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts called Sound Health: Music and the Mind, to expand on the links between music and mental health. It explores how listening to, performing or creating music involves brain circuitry that can be harnessed to improve health and well-being.

Dr. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, said: “We’re bringing neuroscientists together with musicians to speak each other’s language. Mental health conditions are among those areas we’d like to see studied.”

Mr. Braunstein, 63, has experienced the benefits of music for his own mental health and set out to bring them to others by founding orchestras in which the performers are all people affected by mental illness.

Upon graduating from the Juilliard School in his early 20s, he entered a summer program at the Salzburg Mozarteum in Austria, and in 1979 became the first American to win the prestigious Karajan International Conducting Competition in Berlin.

His career took off. He worked with orchestras in Europe, Israel, Australia and Tokyo. At the time, he didn’t have a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

But looking back, he can see that his disorder contributed to his success, and his talent masked the condition.

“The unbelievable mania I experienced helped me win the Karajan,” he said. “I learned repertoire fast. I studied through the night and wouldn’t sleep. I didn’t eat because if I did, it would take away my edge.”

“My bipolar disorder was just under the line of being under control,” he said. “It wasn’t easily detected. Most people thought I was weird.”

He always sensed something was askew. When he was 15, his father took him to a doctor who diagnosed “bad nerves” and prescribed Valium.

As his career progressed, things started to unravel, and his behavior grew increasingly erratic. He was given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder at age 35. His manager dropped him as a client, and he was fired from a conducting job in Vermont.

It was there he met Caroline Whiddon, who had been the chairwoman of the Youth Orchestra Division of the League of American Orchestras. She had been given a diagnosis of depression and anxiety disorder more than 20 years earlier, and had played French horn professionally, which she described as “a notorious instrument that’s known for breaking people.”

Mr. Braunstein reached out to her about creating an orchestra that welcomed musicians with mental illnesses and family members and friends who support them.

“I never thought I’d go back to playing French horn again,” she said. “Ronald gave me back the gift of music.”

Mr. Braunstein called his new venture the Me2/Orchestra, because when he told other musicians about his mental health diagnosis, they’d often respond, “Me too.”

Since the term #MeToo is now associated with sexual assault cases, people sometimes ask if the orchestra is connected to that cause. “It gives us an opportunity to explain that we were founded in 2011,” in Burlington, Vt., “before the Me Too movement began,” Ms. Whiddon said.

In 2014, a second orchestra, Me2/Boston, was created. In between, in 2013, Mr. Braunstein and Ms. Whiddon got married.

Each orchestra performs between six and eight times a year. Each has about 50 musicians, both amateur and professional, ranging in age from 13 to over 80, and they rehearse once a week. New affiliate ensembles in Portland, Ore., and Atlanta follow similar schedules.

Mr. Braunstein gives free private lessons to those who want to polish their skills.

Me2/Orchestra is a nonprofit, and the musicians are all volunteers. Ms. Whiddon raises money through an annual letter-writing campaign to cover expenses, with support from more than 100 donors.

“When we perform at a hospital, center for the homeless or correctional facility,” Ms. Whiddon said, “the cost of that performance is covered by corporate sponsorships, grants or donations from individuals, so the performance is free to those who attend.”

Participating in Me2/Boston allowed Nancy-Lee Mauger, age 55, to pick up the French horn again. The note on the rehearsal door — “This is a stigma-free zone” — made her feel welcome.

Ms. Mauger had played French horn until her mental illness made it impossible to perform. She has diagnoses of dissociative identity disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and depression.

“In 2009, I was playing a Christmas Eve gig,” she said. “It was at the same church, with the same quintet, choir and music that I had played every Christmas Eve for 15 years. This particular night felt different. I had trouble focusing my eyes. At one point, I could not read music or play my horn.”

It lasted about two minutes, and she thought she was having a stroke. In fact, it was her mental illness.

“I learned that little parts of me would come out and try to play my horn during gigs,” she said. “The problem was that they didn’t know how to play. This became such an obvious problem that I quit.”

Now, after four years of intensive therapy, she is able to play again.

At each performance, a few musicians briefly talk about their mental illnesses and take questions from the audience. “Instead of thinking people with mental illnesses are lazy or dangerous, they see what we’re capable of,” Mr. Braunstein said. “It has a positive effect on all of us.”

Jessica Stuart, now 34, stopped playing violin in her mid-20s when she was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. “Joining the Me2/Orchestra in Boston in 2014 was the first time I had played in years,” she said. “I cannot count the ways the orchestra helps me. It has allowed me to overcome the shame I felt about living with mental illness. I no longer feel I have to hide an important part of my life from the rest of the world.”

Jessie Bodell, a 26-year-old flute player who has borderline personality disorder, said he finds rehearsals fun, relaxed and democratic.

He noted that unlike most orchestras, Me2 doesn’t have first, second or third positions. “There isn’t an underlying, tense, competitive feeling here,” he said.

“We’ve seen when you sing or play an instrument, it doesn’t just activate one part of your brain,” said Dr. Collins of the National Institutes of Health. “A whole constellation of brain areas becomes active. Our response to music is separate from other interventions such as asking people to recall memories or listen to another language.”

Partnering with Dr. Collins on Sound Health is Renée Fleming, the renowned soprano and artistic adviser to the Kennedy Center. “The first goal is to move music therapy forward as a discipline,” she said. “The second is to educate the public and enlighten people about the power of music to heal.”

So far the initiative is investigating how music could help Parkinson’s patients walk with a steady gait, help stroke survivors regain the ability to speak, and give cancer patients relief from chronic pain.

“The payoff,” Dr. Collins said, is to “improve mental health. We know music shares brain areas with movement, memory, motivation and reward. These things are hugely important to mental health, and researchers are trying to use this same concept of an alternate pathway to address new categories of mental disorders.”