The Food and Drug Administration is planning to require tobacco companies to slash the amount of nicotine in traditional cigarettes to make them less addictive and reduce the toll of smoking that claims 480,000 lives each year.

The proposal, which could take years to go into effect, would put the United States at the forefront of global antismoking efforts. Only one other nation, New Zealand, has advanced such a plan.

The headwinds are fierce. Tobacco companies have already indicated that any plan with significant reductions in nicotine would violate the law. And some conservative lawmakers might consider such a policy another example of government overreach, ammunition that could spill over into the midterm elections.

Few specifics were released on Tuesday, but according to a notice published on a U.S. government website, a proposed rule would be issued in May 2023 seeking public comment on establishing a maximum nicotine level in cigarettes and other products. “Because tobacco-related harms primarily result from addiction to products that repeatedly expose users to toxins, F.D.A. would take this action to reduce addictiveness to certain tobacco products, thus giving addicted users a greater ability to quit,” the notice said.

The F.D.A. declined to provide further details. But in a statement posted on its website, Dr. Robert M. Califf, the agency’s commissioner, said: “Lowering nicotine levels to minimally addictive or non-addictive levels would decrease the likelihood that future generations of young people become addicted to cigarettes and help more currently addicted smokers to quit.”

Similar plans have been discussed to lessen Americans’ addiction to tobacco products that coat the lungs with tar, release 7,000 chemicals and lead to cancer, heart disease and lung disease. Nicotine is also available in e-cigarettes, chews, patches and lozenges, but this proposal would not affect those products.

“This one rule could have the greatest impact on public health in the history of public health,” said Mitch Zeller, the recently retired F.D.A. tobacco center director. “That’s the scope and the magnitude we’re talking about here because tobacco use remains the leading cause of preventable disease and death.”

About 1,300 people die prematurely each day of smoking-related causes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The obstacles to such a plan, though, are immense and could take years to overcome. Some plans that have been floated would require a 95 percent reduction in the amount of nicotine in cigarettes. Experts say that could toss U.S. smokers, an estimated 30 million people, into a state of nicotine withdrawal, which involves agitation, difficulty focusing and irritability and send others in search of alternatives such as e-cigarettes. Those deliver nicotine without most of the chemicals found in combustible cigarettes.

Experts said that determined smokers might seek to buy high-nicotine cigarettes on illegal markets or across the borders in Mexico and Canada.

Read More on Smoking and Vaping

The F.D.A. would likely have to overcome opposition from the tobacco industry, which has already begun pointing out the reasons the agency cannot upend an $80 billion market. Legal challenges could take years to resolve, and the agency may give the industry five or more years to make the changes.

The effort to lower nicotine levels follows a proposed rule announced in April that would ban menthol-flavored cigarettes, which are heavily favored by Black smokers. That proposal was also hailed as a potential landmark advance for public health and has already drawn tens of thousands of public comments. The F.D.A. is bound to review and address those comments before finalizing the rule.

Other major tobacco initiatives outlined in the landmark 2009 Tobacco Control Act have been slow to take shape. A lawsuit delayed a requirement for tobacco companies to put graphic warnings on cigarette packs. And the agency recently said it would take up to another year to finalize key decisions on which e-cigarettes might remain on the market.

A statement from the tobacco company Altria, the maker of Marlboro, offered a preview of arguments that opponents are expected to make against any rule that drastically slashes nicotine levels. “The focus should be less on taking products away from adult smokers and more on providing them a robust marketplace of reduced harm FDA-authorized smoke-free products,” the company said in a statement on Tuesday. “Today marks the start of a long-term process, which must be science-based and account for potentially serious unintended consequences.”

RAI Services, the parent company of RJ Reynolds, declined to comment on the announcement, but said: “Our belief is that tobacco harm reduction is the best way forward to reduce the health impacts of smoking.”

“Both an express and a de facto ban would have precisely the same effect — both would eviscerate Congress’s expressly stated purpose ‘to permit the sale of tobacco products to adults,’” according to a letter in 2018 from RAI Services to the F.D.A. about an earlier proposal.

Five years ago, Dr. Scott Gottlieb, the agency’s commissioner at the time, released a plan to cut nicotine levels in cigarettes to a minimally or non-addictive level. The proposal took shape in 2017 but did not lead to a formal rule during the Trump administration.

Among the 8,000 comments that poured in on that proposal, opposition emerged from retailers, wholesalers and tobacco companies. The Florida Association of Wholesale Distribution, a trade group, said it could result in “new demand for black market products, and result in increased trafficking, crime and other illegal activity.”

In 2018, RAI Services said that the F.D.A. had no evidence that the plan to cut nicotine levels would improve public health. The agency “would need to give tobacco manufacturers decades to comply” and figure out how to consistently grow low-nicotine tobacco, RAI said in the letter to the F.D.A. The Tobacco control law of 2009 gave the F.D.A. broad powers to regulate tobacco products with standards “appropriate for the protection of the public health,” although the law specifically outlawed a ban on cigarettes or the reduction of nicotine levels to zero.

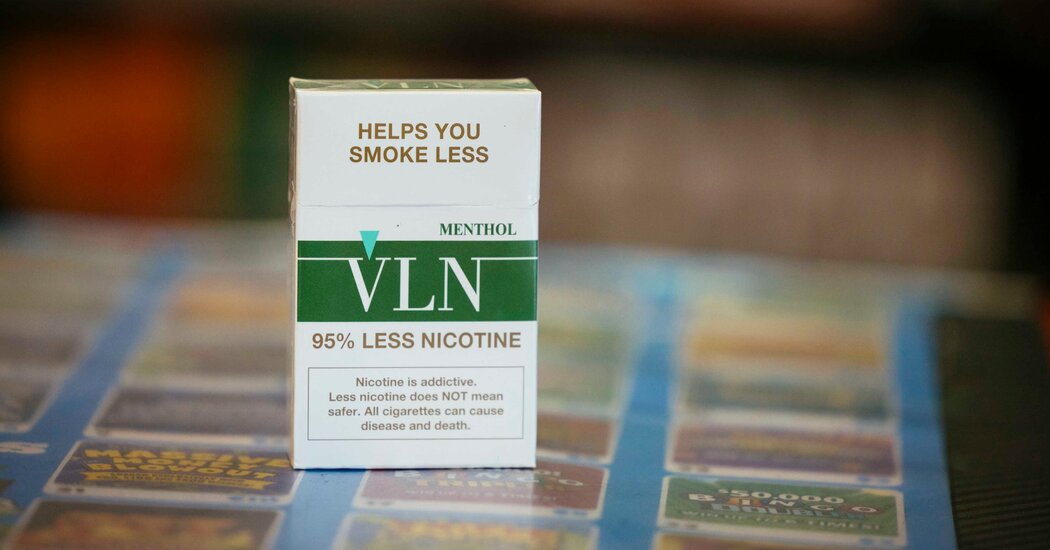

Low-nicotine cigarettes are already available to consumers, albeit in a limited fashion. This spring, a New York plant biotech company, 22nd Century Group, began selling a reduced-nicotine cigarette that took 15 years and tens of millions of dollars to develop through the genetic manipulation of the tobacco plant. The company’s brand, VLN, contains 5 percent of the nicotine level of conventional cigarettes, according to James Mish, the company’s chief executive.

“This is not some far-off technology,” he said.

To earn its F.D.A. designation as a “reduced-risk” tobacco product, VLN was subjected to a raft of testing and clinical trials by regulators.

For now, the company is selling VLN at Circle K convenience stores in Chicago as part of a pilot program. Mr. Mish described sales as “modest” — retail prices are similar to premium brands like Marlboro Gold — but he said the F.D.A. proposal would most likely accelerate plans for a national rollout in the coming months.

Dr. Neal Benowitz, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, who studies tobacco use and cessation, first proposed the idea of paring the nicotine out of cigarettes in 1994.

He said one key concern was whether smokers would puff harder, hold in smoke for a longer time or smoke more cigarettes to compensate for the lower nicotine level. After several studies, researchers discovered that the cigarette that prevented those behaviors was the lowest-nicotine version, one with about 95 percent less of the addictive chemical.

Dorothy K. Hatsukami, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Minnesota who studies the relationship between nicotine and smoking behavior, said a growing body of evidence suggested that a rapid and significant reduction of nicotine in cigarettes would provide greater public health benefits than the gradualist approach that some scientists had been promoting.

A 2018 study led by Dr. Hatsukami that followed the habits of 1,250 smokers found that participants who had been randomly assigned cigarettes with ultralow nicotine smoked less and exhibited fewer signs of dependency than those who had been given cigarettes with nicotine levels that were gradually reduced over the course of 20 weeks.

There were, however, downsides to slashing nicotine in one fell swoop: Participants dropped out of the study more frequently than those in the gradualist group, and they experienced more intense nicotine withdrawal. Some secretly turned to their regular, full-nicotine brands.

“The bottom line is we’ve known for decades that nicotine is what makes cigarettes so addictive, so if you reduce the nicotine, you make the experience of smoking less satisfying, and you increase the likelihood that people will try to quit,” she said.

A recent study offers a cautionary tale, though, on the degree of public health benefit that lawmakers can expect from tobacco-control policy. While there is no other nation to look to for experience with a low-nicotine cigarette mandate, there is for the menthol flavor ban.

Alex Liber, an assistant professor in the oncology department of Georgetown University’s School of Medicine who studies tobacco control policy, examined Poland’s experience with a menthol cigarette ban instituted in 2020.

The study he and others wrote found the ban did not lead to a decrease in overall cigarette sales, Mr. Liber said, probably because tobacco companies cut cigarette prices and also began selling flavor-infusion cards (for about a quarter each) that users can put in their cigarette pack to add back the flavor. (Some experts say any move to sell flavor-infusion cards in the U.S. would likely be illegal.)

“They know how to sell and make money and they will make more and more as long as they have wiggle room,” he said. “I just expect nothing less.”

Zolan Kanno-Youngs contributed reporting from Washington.