With Kurt Cobain, Tupac Shakur, Elliott Smith and Jeff Buckley gone, that undersized, underwhelming demographic known as Generation X was already short on idols. And after the death this past Tuesday of Elizabeth Wurtzel, the “Prozac Nation” author and 1990s-angst poster child, our confused, self-contradictory cohort may have lost the most Gen X member of us all.

Ms. Wurtzel, who died of metastatic breast cancer at 52, was well cast to serve as a face for a generation that the news media perpetually cast as nihilistic and irony-suffused — latchkey kids whose prospects were dimmed by recession and an America in decline.

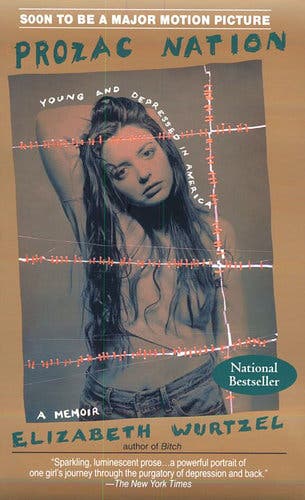

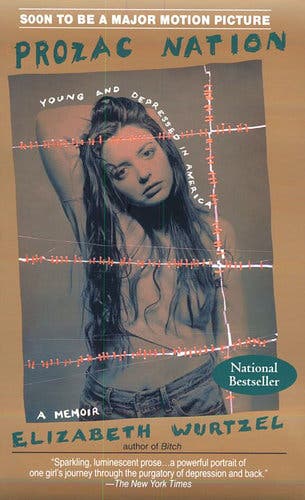

She certainly had the look: A cover-worthy grunge-pixie image consisting of bare-midriff tops, streaked hair, Goth black eyeliner and a perpetual rock star pout. Not for nothing was she called “the Courtney Love of letters.”

For proof, look no further than the original cover of her 1998 book, “Bitch: In Praise of Difficult Women,” where she posed topless and smirking, proudly displaying a middle finger to the world.

A jaded distrust of institutions apparently came naturally. As a pioneer of the ’90s memoir boom, Ms. Wurtzel was either burdened or blessed with the tangled upbringing that launched a thousand Gen X clichés.

She was not only a child of a divorce, like so many in her generation, but, in some sense, the confused product of the loose social mores of the ’60s.

As she recounted in the Cut in 2018, the man she grew up thinking was her father “was not so much wrong for me as wrong for anyone. He relied on pills to get by.” Her real father, as she found out late in life, was the celebrated ’60s civil rights photographer Bob Adelman, with whom her mother had had an affair. It somehow seems very Gen X that she was born in July 1967, the hippie pinnacle in the Summer of Love.

As for those famously gloomy career prospects which supposedly doomed her generation — at least until the dot-com frenzy took off in the late ’90s — it was hard to call hers dire. Ms. Wurtzel grew up in Manhattan (albeit the gritty Manhattan of the ’70s, where Zsa Zsa Gabor, she once wrote, was mugged in the Waldorf Astoria ), attended the elite Ramaz School, and later received a bachelor’s degree in comparative literature from Harvard.

Nevertheless, she entered adulthood haunted by a very Generation X sense of meaninglessness and despair, largely due to the crippling depression that she recounted in excruciating detail over the course of 317 pages in “Prozac Nation,” the 1994 memoir that made her a star at 27.

“I feel like a defective model, like I came off the assembly line flat-out,” she wrote, using an obscenity, “and my parents should have taken me back for repairs before the warranty ran out.” The book not only helped kickstart a memoir boom in literary circles, but foreshadowed the squirm-inducing oversharing of the coming social media age.

Ms. Wurtzel’s psychic suffering, which, like Mr. Cobain, she turned into a form of performance art, dovetailed neatly with the disaffection and lack of direction that bedeviled her generation, at least in a pop culture sense, according to seminal ’90s movies like “Slacker” and “Reality Bites.”

During her ’90s youth, she was a self-defined “20-nothing,” having survived messy sex episodes and a suicide attempt to embark on a career that seemed to crest and collapse simultaneously. After losing a gig interning at the Dallas Morning News after accusations of plagiarism, she briefly became a rock critic — how Gen X! — for an eye-blink at New York Magazine and later, The New Yorker, where she was let go as soon as Tina Brown took over.

Of course there were drugs. And not just Prozac. Ms. Wurtzel was soon doing cocaine and heroin, and found herself addicted to Ritalin, which she did not “take” so much as snort, as she recounted in her 2003 addiction memoir, “More, Now, Again.”

And, like any worthy X-er, she tended to fall back on irony to weather the storm, as exemplified by the Prozac locket she flashed in her ’90s heyday.

No wonder that Ms. Wurtzel, at her depths, got to the point where she could not even sign off on the basic tenets of reality. “Good and bad are not opposites, they are both just different forms of intensity,” she wrote in “Bitch,” channeling either enlightenment or Charles Manson.

Her role as a generational spokeswoman did not end with the era of flannel shirts and Zima. In a 2012 New York Times article about the first member of the generation — Representative Paul D. Ryan — to appear on a presidential ticket, I interviewed Ms. Wurtzel, along with Johnny Knoxville of “Jackass” and Krist Novoselic of Nirvana, about that theoretically historic moment. Ms. Wurtzel served up a typically ’90s shrug of a response: “Vice president: it’s the perfect Gen X job, isn’t it? To have no responsibility, to have only the perks of what was left behind by the responsible people.”

As a generational symbol, however, Ms. Wurtzel did fail in one regard: She did not die young— at least not exceptionally so. Indeed, her life in her final years might be seen as a violation of everything she once symbolized.

The woman who described herself in “Prozac Nation” as “the girl you see in the photograph from some party someplace or some picnic in the park, the one looks so very vibrant and shimmery, who is in fact soon to be gone,” lived to earn a law degree from Yale and work for a time at the prestigious law firm, Boies Schiller Flexner. The woman who wrote in that same book that “no one will ever love me; I will live and die alone” did eventually get married, to a writer named James Freed Jr., in 2015.

That same year, she underwent a double mastectomy. After a diagnosis of breast cancer, caused by the BRCA genetic mutation, she became an advocate for BRCA testing — something she had not had — and encouraged Ashkenazi Jewish women, in particular, to push for the test in an op-ed for The New York Times. “It seems I am the designated driver at my Seder table,” she wrote.

Some die-hard fans from the ’90s might consider her newfound advocacy and domestic turn a surrender.

But to the rest of us, it suggests that “Generation X,” a term that has largely vanished from the cultural landscape, was less a demographic group than a phase, a youthful illusion that, like Kurt and Biggie, was never destined to make it to 30.

Ms. Wurtzel surely felt no shame in settling down.

“Shame,” she wrote in an afterword to a 2017 reissue of her seminal memoir, “is a terrible thing. You are only as sick as your secrets.”