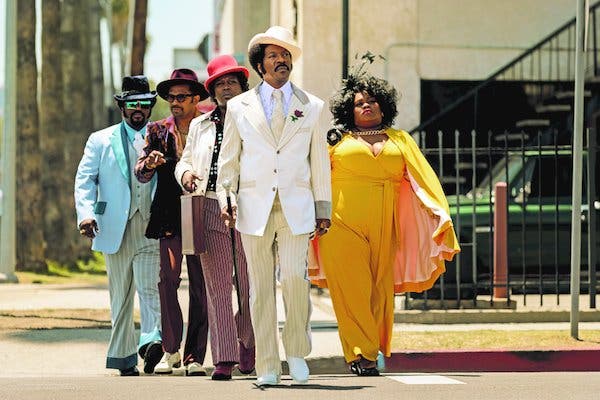

Will Eddie Murphy and his natty cohort in “Dolemite Is My Name” bring back the double-knit polyester leisure suit?

Don’t bet on it. But what the movie may spawn, in some quarters at least, is yet another round of 1970s-inflected-Afro urban chic.

There is plenty of hustle in Mr. Murphy’s latest film, which arrived in theaters last week and will be on Netflix starting Oct. 25. In this upbeat biography of Rudy Ray Moore, the record store clerk turned entertainer and his stage persona Dolemite, the actor slips nimbly into character. His dapper suits, carnival-stripe bell-bottoms and platform shoes, the winged lapel of his dinner jacket invariably punched with a bright carnation, function as a liberating second skin.

His regalia is matched by the riotous costumes his companions flaunt, their high-crown Homburgs, fur-collared coats and slickly patterned polyester shirts, plumage ripe for the plucking by a novelty-parched style establishment.

Fashion’s pilfering of black urban style hardly comes as news to Ruth Carter, the “Dolemite” costume designer, who won an Academy Award earlier this year for her work on “Black Panther.”

“In fashion, urban cultures tend to lead the way,” Ms. Carter said. “When we pick up something over the top and even gaudy, wear it and bring it down to a more realistic level, it tends to catch on.”

That it does. Over the years some of those Afro-urban influences have filtered onto establishment runways, among them that of Marc Jacobs, who provoked social media furor when he sent white models onto his catwalk crowned in Afros and dreadlocks.

More recently, and more notoriously, Alessandro Michele, the Gucci creative director, stirred a tempest when he plucked inspiration from the ’70s workshop of Dapper Dan (Daniel R. Day), the much mythologized Harlem tailor, but failed to credit his source. Mr. Michele and Mr. Day eventually collaborated on a fashion line.

From Ms. Carter’s perspective, fashion’s impulse to borrow seems natural, if not downright inevitable. “The ’70s in urban America had its own individual look and style,” she said. “People wanted a piece of it.”

Still, in its way, the movie represents a take-back, the reclaiming of a sartorial heritage that has leached bit by bit into the cultural mainstream.

“There were lot of kooky things you could do in the ’70s and now to make yourself kind of a clown,” Ms. Carter said. “But this is a film where you look a little deeper into all of the details about this time, and your job is to make people look good.”

The film’s splashy style, its untrammeled exuberance, was embodied in the day by Mr. Moore, a small-time comedian bent on coolly defying the odds to become a trash-talking recording artist and, ultimately, the star of his own roughly cobbled films.

Dolemite, his sedulously designed alter ego, can be thought of as an early influencer, his raunchy, rhyming patter a progenitor of ’80s rap, his rakish wardrobe conceived to captivate an avid following.

His look had its origins in the smoky, boozy nightclubs where he performed, his costumes both a sendup and a homage to the ’70s-era blaxploitation genre. The fur-collared maxi-coats, the pinstripe suits, the boutonnieres worn by the class-conscious heroes and villains of “Superfly” and “Shaft” were aspirational, Ms. Carter said. Their wardrobes, which bore the stamp of Savile Row, were modified and showily accessorized for impact.

“The pimp takes that suit and blows it out,” she said. “His only rule is that there are no rules.”

The pimp owes a less obvious debt to the 19th-century dandy, all style and swagger in his high top hat, tight waistcoat and ruffle-front shirt — that last a Dolemite signature.

Mr. Murphy’s flamboyant character may have also taken a page from Robert Beck, better known as Iceberg Slim, the outlaw hero of “Pimp: The Story of My Life,” a 1967 fictionalized autobiography and a repository of pimp philosophy and style.

Always on the prowl for sporty vines (suits) and fancy trimmings, “I would press five-dollar bills into the palms of shine boys,” Beck writes. “My shoes would be handmade, would cost three times as much as the banker’s shoes.”

After all, as he reasons in another passage, “few can resist the charms of exclusivity in its myriad forms.”

Just as colorful an influence: Mr. Moore’s travels on the chitlin circuit, performing and selling his self-produced albums out of the trunk of his car. “What I loved best about people in that time was that they created a subculture,” said Ms. Carter, who is 59. They were unapologetic in taking a stance, in creating the black community of the South.

“They went to juke joints and back-alley clubs, sat with their legs crossed wearing sequined bright yellow hats, bright pink suits, white shoes — we called them marshmallows — and white fur hats. They enjoyed their community that was a little rude and crude.”

No less rude than Dolemite himself, whose resplendence in the film was in studied contrast with his companions’ relatively subdued civilian wardrobes. For those, Ms. Carter turned to Sears catalogs and magazines including Jet and Ebony.

For more extravagant departures, she plumbed Eleganza, a defunct catalog replete in its day with shirts bearing floppy nine-inch “dog ear” collars, madly striped flares, leather or denim patchwork coats and two-tone double-knit jumpsuits fashioned, as the catalog copy proclaimed, from “luxurious 100 percent Orlon acrylic!”

She ran up some costumes from scratch, among them a line-for-line replica of the powder blue suit Mr. Moore wore in his 1976 action comedy, “The Human Tornado.”

Stimulating though it may have been, Dolemite’s larger-than-life persona, built largely on his wardrobe, may have left some fans queasy, Ms. Carter acknowledged.

“At one time people were afraid to like it,” she said. But now, among mainstream filmgoers, it’s as apt to prompt envy. “Those costumes give people the freedom to play,” she said. “Who wouldn’t want some of that?”