I know a guy — he collects unemployment even though he’s employed — who just had his teeth veneered bright white, with ceramic laminates. I ran into him recently, and he dropped to his knees to coo over how my puppy has grown. As he went to kiss her freckled nose, he flashed his crocodile smile. That same week, I heard from another guy — last I knew, he was a real mess, drove his marriage off a cliff, with his kids in the back seat — letting me know he’s now a life coach and focus counselor. He wants to help me live my best life and was offering me a 20 percent discount. Spring, that powerful season of rebirth, has sprung.

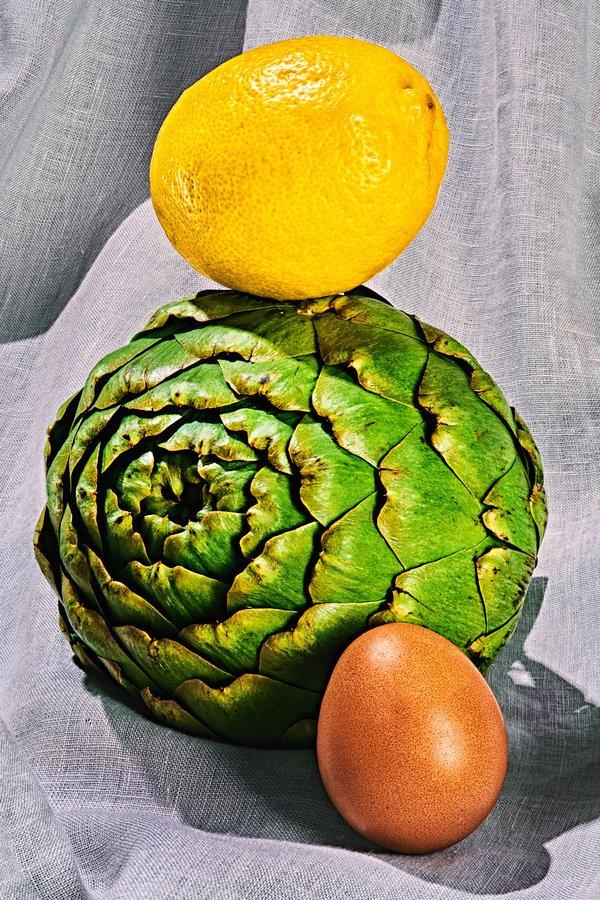

My artichokes, on the other hand, are already at their peak and showing up as they always have: bitter, impenetrable and hostile on contact. The first thing they do is stab you in the fingertips, with their incredibly sharp thorns that crown each leaf. This is the nature of the artichoke itself, upon arrival — hard, heavy, tight, coated with a film that is unpleasant on your palms and abhorrent to taste. No sooner have you been stabbed by one of her thorns than you impulsively suck your fingertip to soothe it and are stricken by a bitterness so profound it sends you spitting and sputtering into the nearest sink. You persevere and trim all the spikes and cut away the tough outer leaves as instructed, then you cut the lemons the recipes so often ask you to use in an attempt to keep the artichoke from turning the color it wants to: drab. Instantly your hands are now practically effervescing with a live painful stinging as the lemon juice makes contact with the cuts on your fingertips. All this customary mishandling of the vegetable merely confirms what you already fear and dislike: The artichoke as a terribly intimidating object. I adore them.

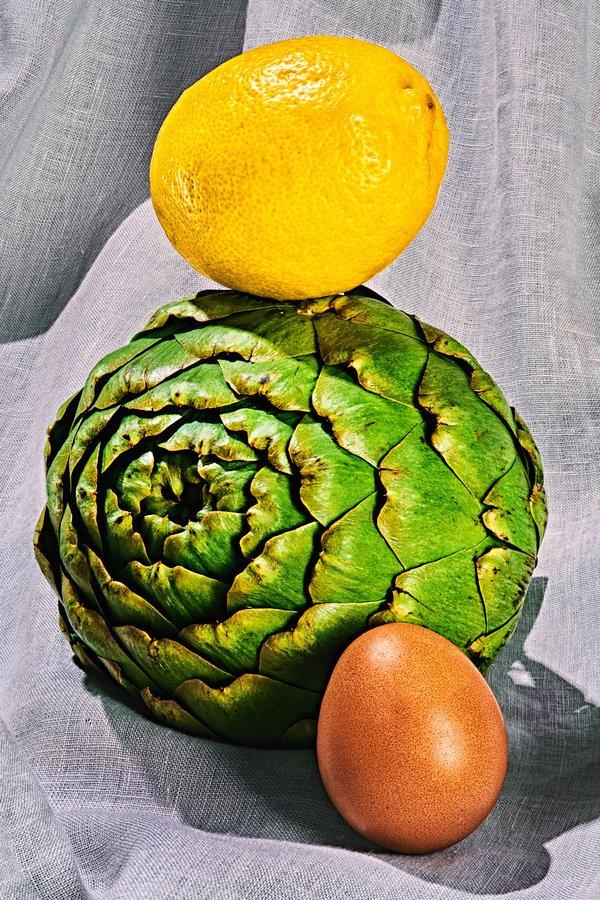

Bitter, impenetrable, hostile — but worth getting to the tender heart.CreditBobby Doherty for The New York Times. Food Stylist: Maggie Ruggiero. Prop stylist: Margaret MacMillan Jones.

Once you get to the heart of them — the tenderest part — they reveal an unmitigated sweet, nutty goodness. And getting to that goodness is not difficult at all, if you just accept the thistle for what it is and go with it, not against it. You hug a porcupine from the front, not the back, obviously. Why not keep your hands off her, since that is what she seems to be so clearly telling you? Instead, place the artichoke whole — spikes and all, stems intact — right into the boiling water and let her shed all her thorns of her own free will: They will soften and fall off and settle at the bottom of the pot, rendering each leaf defanged and now painless to grasp with your fingers. And let’s accept that she is going to be drab. Let’s not whiten her teeth. No need to acidulate the water or put lemons or baking soda in the boil to alkalize. Just leave her be. When cooked exactly to doneness, the thicket of choke protecting the innermost heart can be pried away with nothing sharper than your gentle thumb. If it resists, you can be sure it’s your fault; you have undercooked it.

Dressing the now-cooked artichoke is a pleasure that you can take in many directions, a bit like pairing food and wine — you can go against its sweet and earthy flavor with high-acid ingredients like capers and diced tomatoes and briny olives; or tarragon vinegar, minced shallots and black pepper; and finish with a long pour of an astringent first-press olio verde that attacks the back of the throat. But because I’m arguing at the outset here for going with the artichoke, and because I’m featuring the entire artichoke, alone, rather than parsed and used as an ingredient in a larger dish (with shell beans and mint in a ragout; with stewed leeks and flageolets to go with lamb chops; marinated with salami and provolone in an antipasto), I don’t want to distract. Here, where the artichoke itself is the whole show, a simple homemade mayonnaise.

Have you had that experience of taking a sip of water after eating an artichoke and been startled to think someone had stirred a tablespoon of white sugar into your glass? And have you had a glass of dry wine ruined after a bite of artichoke, when the wine suddenly tastes like some grapy thing you’d find in a toddler’s sippy cup? Because the cooked meats are so particular and impart such a sweetness, I’m inclined to keep going in a soft direction with a mild, silken whole-egg mayonnaise. This is not the place for a big garlicky number or a spicy mustardy one to be in conflict with the artichoke’s subtle nature.

I make some 11 or more mayonnaises — one yolk, one whole, three yolks no wholes, triple yolk no garlic, triple garlic no mustard, one whole two yolk, two yolks six cloves, dry mustard, wet mustard, saffron, Pernod, olive oil, grapeseed oil, blended neutral oil — and I’d guess you do, too. To get the best out of this supremely elegant dish, my counsel would be to focus on the family, so to speak, and use sunflower oil in your mayonnaise. The sunflower is the tall, gangly cousin of the complicated, prickly artichoke, and as we all know, she does not even try to disguise her black heart.