It can be hard to find common ground in Washington these days, but furor over drug prices could be one exception. Many Americans continue to struggle to pay for the prescription medicines they need. And rising drug costs are a problem for insurers and taxpayers, too — treatments for some rare diseases are topping $2 million.

As the presidential election heats up, politicians from both parties are eager to show they are doing something about a hot populist issue, and bipartisan solutions are beginning to take shape. Some proposals, like placing a limit on what older Americans must pay out of pocket for drugs, could make an immediate difference to people struggling with high costs. Others, like shutting down the games that pharmaceutical companies play to avoid competition, are more theoretical. They could streamline a complex system, but are unlikely to immediately lead to lower prices at the pharmacy counter.

Here’s a guide to some of the proposals.

Use the power of the federal government to negotiate with drug companies.

Progressive Democrats have long argued that the federal government should be able to directly negotiate the price of drugs in Medicare, the health care program for older Americans. Under the current system, private insurers negotiate with the drug companies.

Now, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi is said to be floating a compromise — one that would require the federal government to directly negotiate the price of about 250 expensive drugs a year. Under her proposal, which has not yet been introduced, the Department of Health and Human Services would negotiate with drug makers.

Companies that do not comply could face a tax equal to half of that drug’s sales from the previous year. Unlike some other plans, Ms. Pelosi’s proposal ensures the same government-negotiated prices would be available to commercial insurance plans.

Since a small number of drugs accounts for a major chunk of pharmaceutical spending, significantly lowering the price of even a few hundred drugs could go a long way toward lowering overall costs.

But whether her proposal will succeed is far from clear. The idea is likely to face opposition from many Republicans, who contend that private insurers are best equipped to negotiate with drug companies, and who may also be averse to imposing a steep tax on a major American industry.

Some progressive Democrats pushed Ms. Pelosi to expand the number of drugs that could be negotiated, from at least 25 drugs to the current 250. They favor an even broader plan that would affect all drugs.

Still, Ms. Pelosi’s plan should not be discounted — her office is in talks with the White House over a drug pricing deal that may include this proposal. President Trump has voiced support for the idea of direct negotiation before.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Democrat of California, speaking about health care in May.CreditErin Schaff/The New York Times

Lower out-of-pocket costs for Medicare beneficiaries.

As one of the Trump administration’s major drug price initiatives, this proposal aims to reduce the costs that many older residents face at the pharmacy. Medicare consumers are often forced to pay out-of-pocket costs based on a list price, even when — behind the scenes — private pharmacy benefit managers have negotiated bigger discounts, or rebates, with the manufacturer.

The Trump administration’s plan would eliminate the legal protections for rebates, and require discounts to be passed along to consumers. Alex M. Azar II, the health and human services secretary, has said he hopes the change will simplify a broken system and give manufacturers an incentive to lower their list prices.

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

But the true impact of the rule is far from clear, and the change could raise costs in other parts of the chain. While it would save some people money on out-of-pocket expenses, it is expected to raise drug-plan premiums for all Medicare beneficiaries, and it also would quite likely cost the federal government money. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office concluded in May that the rule, if adopted, would cost taxpayers $177 billion within 10 years.

The rule is also unusual because — unlike many other proposals to bring down drug costs — it is supported by the pharmaceutical industry, which has put part of the blame for rising prices on pharmacy benefit managers. Insurers and pharmacy benefit managers say the rule would stymie their ability to effectively negotiate with drug makers.

The Trump administration has signaled that it is likely to finalize the rule some time this year.

Cap out-of-pocket spending under Medicare.

The drug coverage program known as Part D, for those who are 65 and older, has no limit on out-of-pocket spending. People who need expensive drugs (such as for cancer treatments or other serious diseases) can wind up paying thousands of dollars.

In addition, once a patient’s drug spending reaches a certain level in a year — $5,100 in 2019 — the federal government picks up most of the bill, rather than the private insurers who operate the drug plans.

There is some bipartisan support for capping out-of-pocket spending, as well as for shifting more responsibility for the higher costs onto insurers and drug makers. A proposal by House Democrats and Republicans would limit annual out-of-pocket spending to $5,100. Senator Charles Grassley, Republican of Iowa and chairman of the Finance Committee, has also expressed support for an out-of-pocket spending limit, as well as for shifting more of the financial responsibility to drug makers.

With members of both parties expressing support for this idea, it holds the promise of being one of the most significant moves that Congress could make this year to directly lower consumers’ drug costs.

Tie the price of some drugs to what they cost in other countries.

Another major proposal by the Trump administration would limit the price of some drugs covered by Medicare that are administered in a clinic or doctor’s office — expensive medications used for serious illnesses like cancer — by tying them to an index based on the price of the drugs in other countries.

The United States pays higher prices for drugs than any other country does, a situation that Mr. Trump describes as “global free-riding.”

The proposal is an unorthodox move for a Republican president, because it would effectively ride the coattails of countries with universal health care systems, such as France.

It is also fiercely opposed by an array of powerful lobbying interests, including the pharmaceutical industry — which described the proposal as “foreign price controls.” Health care providers also profit from the existing system and have opposed the proposal, warning that it could have “unintended consequences.”

The Trump administration may issue a proposal by the end of this year.

Restrict the games drug companies play to avoid competition.

Drug companies love the word “innovation” when they talk about drug development, but they are also famously innovative in coming up with ways to shut down competitors.

Several bills in Congress — many with bipartisan support — address the tactics these companies use to maintain monopolies. Some proposals have passed the House and have bipartisan support in the Senate, including one that would force brand-name drug makers to turn over samples of their drugs to would-be competitors so cheaper copies can be developed. Other measures would limit the so-called “pay-for-delay” deals brokered by brand-name drug companies and generic manufacturers to postpone competition.

Congressional observers say that of all the proposals, these have the best chance of becoming law. But while they are tweaks that make the existing system work more smoothly, they may not have a significant effect on prices.

Require drug companies to list their prices in television ads.

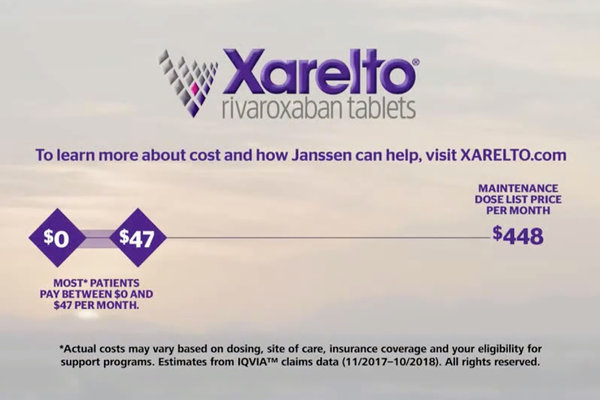

The most visible step the Trump administration has taken to address drug costs is expected to be implemented this summer, when pharmaceutical manufacturers will be required to post in television advertisements the list price of drugs that cost more than $35 a month. (A disclaimer will note that patients covered by health insurance are likely to pay less.)

Although the measure doesn’t directly reduce prices, Mr. Azar has said he hopes the move will shame drug makers into lowering them.

On Friday, three major drug makers — Merck, Eli Lilly and Amgen — filed a federal lawsuit seeking to block the rule, arguing that it violated their First Amendment rights and would mislead consumers.