For as long as I can remember, I’ve had this image of Christmas: a village nestled in a snowy valley, candlelit windows glowing against a night sky. I’m not sure where it came from. Growing up in sunny Southern California, my family strung lights on the palm trees in our yard and went to the beach on Christmas Eve. Most kids know about Santa’s sleigh, but I believed he traveled on a magic speedboat.

As an adult, I’ve searched for that old-fashioned Christmas, one of snow-tipped Yuletide cheer, sleigh rides, sugarplums and freshly cut pine trees trimmed with handcrafted ornaments. Though I visited the Christmas markets in European capitals like London, Paris and Vienna, I never really found it. Yes, the fairy lights twinkled, the sweet scent of mulled wine drifted, and sometimes snow crunched under my heels. Yes, the market stalls displayed an array of glittering ornaments for the tree and home. Yet upon closer inspection, the decorations were flimsy, their designs repeating from vendor to vendor as if they shared the same supplier: an industrial factory in a distant land.

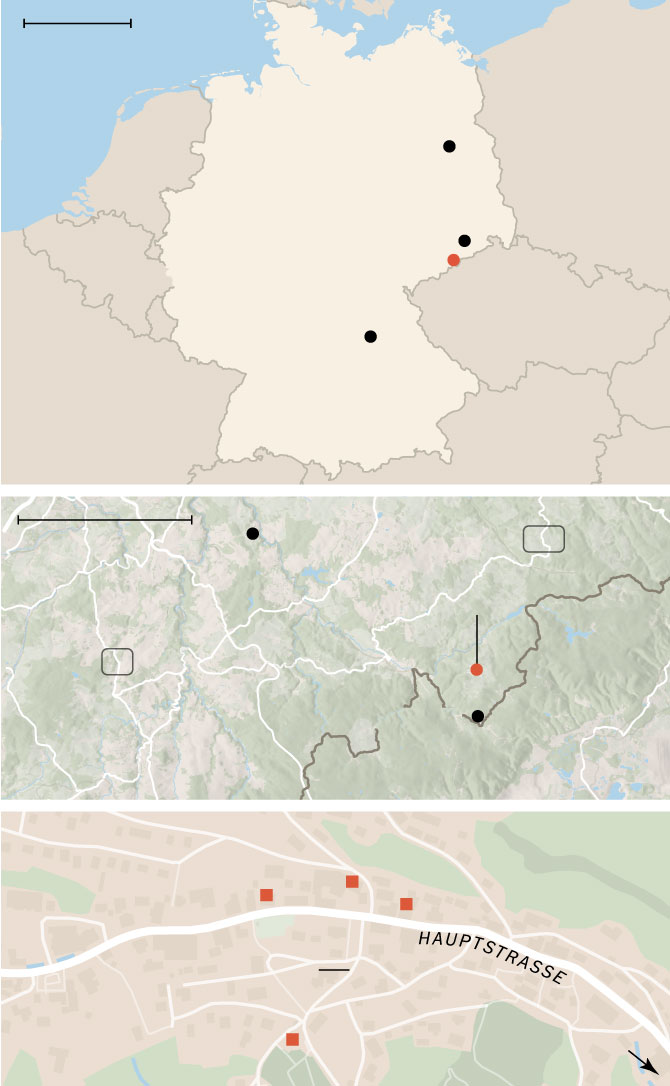

Was my vision of Christmas a relic of fairy tales? Or could it still exist in a country that celebrates the Christmas tree with a traditional folk song, “O Tannenbaum”? When I recently reconnected with a high school friend who had moved to Germany, I asked her about German Christmas markets, expecting her to extol the storybook wonders of Nuremberg or Dresden. Instead, she described a place I’d never heard of: the “Christmas ornament town” of Seiffen in the Erzgebirge, or Ore Mountains, a rural part of Saxony so devoted to holiday décor that Germans call it the “home of Christmas.”

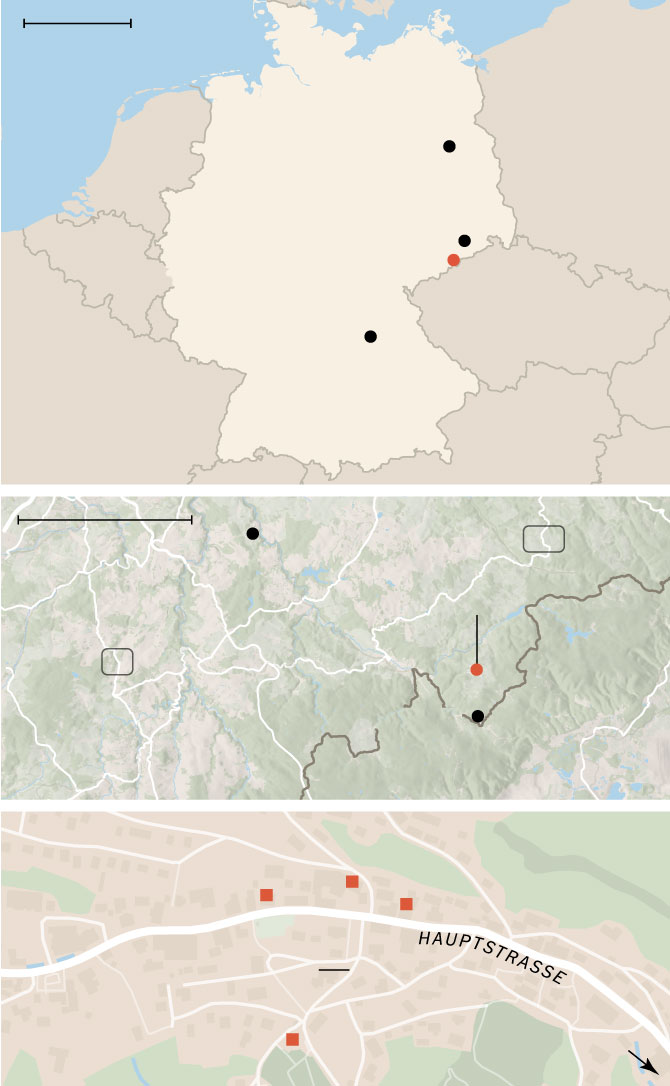

Could this be the artisanal Christmas idyll I’d been dreaming of? To find out, I spent a few days in mid-October in this far eastern region of the former German Democratic Republic near the Czech border, immersing myself in the Erzgebirge’s traditional folk art.

Today the region is famous among collectors around the world for its handcrafted wooden Christmas ornaments, including nutcrackers, pyramids that spin in the heat of candles, and smoking men (wooden incense holders carved as miners and other figurines). Many Erzgebirge Christmas decorations honor the region’s mining history. (Mining is so important here that in July UNESCO named the region a World Heritage site in recognition of its mining activity from the 12th to the 20th centuries.) As mining production began to wane in the 17th century, residents turned to woodworking and toy-making.

My trip began with a 50-mile drive from Dresden’s airport to the town of Seiffen, which was easier than you’d think for a road that winds through a mountain range (albeit a low one), twisting gently to reveal slopes and green valleys dotted with farms. At the Seiffen town limits, a sign proclaimed it the “Spielzeugdorf,” or toy village, and I noted nutcrackers adorning the gaslit street lamps. After dropping off my bag at Buntes Haus, a spotless, family-run hotel in the center of town, I headed out to explore by foot.

I knew I was too early for Seiffen’s renowned Christmas market, which is held annually during the Advent season (the period that includes the four Sundays preceding Christmas), and I feared I was too early for Christmas at all. And then I ran into two competing food stands — one on each side of the street — the type of rough timber huts I associate with outdoor markets. Though it was a beautiful fall day, sunny and mild, a few families and couples had gathered at each stand eating grilled bratwurst and sipping mugs of glühwein, or mulled wine.

CZECH

REPUBLIC

Grünhainichen

Deutschneudorf

CZECH

REPUBLIC

Ore

Mountains

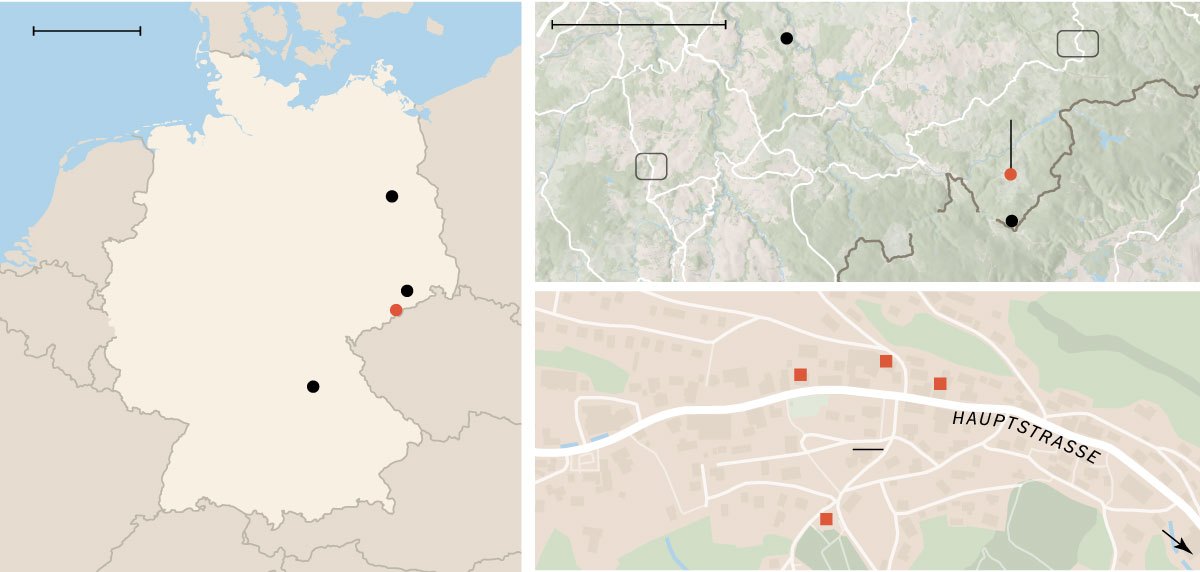

Buntes Haus

Wendt & Kühn

Handwerksmarkt

Deutschneudorfer

strasse

To Freilichtmuseum

Bergkirche

Grünhainichen

CZECH

REPUBLIC

Deutschneudorf

Ore

Mountains

Buntes Haus

CZECH

REPUBLIC

Wendt & Kühn

Handwerksmarkt

Deutschneudorfer

strasse

To Freilichtmuseum

Bergkirche

Clearly I had come to the right place.

Indeed, as I perused the workshops and galleries lining the Hauptstrasse, or main street, I found every single one bursting with hand-carved, brightly painted Christmas decorations. They ranged from thimble-size angels to spinning pyramids as tall as I am, to nutcrackers, Santas, woodsmen and more. Individually, each figure was exquisite, the fine details and droll expressions clearly the work of expert artisans. Collectively, however, they became overwhelming — the colors, tiny limbs, and faces turning into a blur of clutter.

Happily for my untrained eye, I found a guide in Susann Blaschke, the online manager of Wendt and Kühn, a family-owned producer of Erzgebirge figurines. Founded in 1915 by two women, Grete Wendt and Margarete Kühn — “they were unusual for the time,” Ms. Blashcke said— today the company is in its third generation of Wendt family owners.

Production takes place in the nearby village of Grünhainichen, but the boutique in Seiffen sells a bevy of hand-painted wooden collectibles: rosy-cheeked blossom children, or blumenkinder, toting oversized flowers; kerchiefed peasants gathering berries; dainty angels, their green wings adorned with 11 trademark dots of white; and more. Inspired by local flora and suffused with Old World charm, “almost all the designs were created by the founders or Olly,” said Ms. Blaschke, referring to Olly Wendt, who married Grete’s brother, Johannes, in 1929.

Each figure takes about six weeks to create, and a five-person team is dedicated to painting only the faces to ensure consistency. The whimsical creations have a devoted international fan base and are exported to more than 25 countries.

Before I left the shop, Ms. Blaschke described some of the other crafts traditionally produced in the Erzgebirge. A few I knew: candle arches, nutcrackers and the Christmas pyramids, those small, delicate, tiered wooden carousels that are lit with candles and topped with a propeller that turns in the heat of the flames. But when she tried to describe the small wooden animals and figures called ring-turned toys (in German, Reifentiere), we both conceded linguistic defeat.

The next morning, after having breakfast amid nutcrackers and candle arches in my hotel’s dining room, I headed to the Freilichtmuseum, or Open-Air Museum to learn about ring-turned toys as well as the history of the Ore Mountain region. On the outskirts of Seiffen, tucked into a stream-fed valley, the folklore museum is a collection of mostly 18th- and 19th-century buildings gathered to form a traditional Erzgebirge village.

A cold rain fell during my self-guided visit but as I dashed from house to house, I told myself the damp weather and gusts of wind conjured up a Christmas-y mood. I thrust my icy hands into my coat pockets and tried not to gaze too longingly at the unlit tiled oven-stoves that had once served as a home’s sole source of warmth.

Through dusty windows I peered into a half-timbered, 18th-century miner’s house, the cramped, primitive conditions (the living room next to a goat stable, for example) illustrating the region’s historic poverty. In the 15th century the Erzgebirge was the most important source of silver in Europe — but mining wages were so meager, many workers supplemented their incomes with farming or woodworking. As the veins began to dry up in the 18th century, the local economy started to rely heavily on side gigs like woodworking, which evolved into toy making.

The toasty scent of sawdust greeted me at the ring turner’s workshop, which was built in 1758. Inside, a veteran craftsman in a striped blue shirt and jeans worked in the yellow glow of a spotlight. Ring-turned toys are named after their production method (and not to be confused with windup toys that move by twisting an attached ring or winding key). The “ring” is actually a circle of wood that is “turned,” or carved, on the lathe to create a grooved wheel. This carved ring is then sliced with a knife — sideways, like a loaf of bread — so that the cross-section forms the crude outline of a figure, which is refined, carved and painted. Each ring produces a different creature: an elephant, rabbit or bear.

Ring-turned toys were invented in Seiffen around 1800. “It was a special technique to cheaply produce wooden animals,” said Konrad Auerbach, the director of the Erzgebirge Toy Museum in Seiffen. We were standing in the museum’s main gallery surrounded by displays of antique ring-turned animals. Seiffen became one of the continent’s leading toy producers, fueled in part by the Erzgebirge’s relative proximity to Nuremberg, then “the center of the European toy trade.” Dr. Auerbach said.

The region’s tradition of making highly detailed and handcrafted Christmas ornaments “also began here in the 1800s,” Dr. Auerbach continued as we gazed at an enormous, 19th-century Christmas pyramid. “Not for production, not for selling, but just made for the home, for the family.”

Toymakers created holiday decorations that reflected the Erzgebirge’s mining history. The candle arch, for example, resembles the entrance to a mine; like the Christmas pyramid, it features a blaze of candles symbolizing the mineworker’s constant desire for light. During the Advent season, towns throughout the Erzgebirge still host miners’ parades, the marching ranks dressed in traditional uniforms that resemble 19th-century military garb.

Upstairs, the museum traced the gradual decline of the local toy industry’s golden era, from the advent of metal toys in the early 20th century, to the rise of holiday decorations under the Communist German Democratic Republic of 1949 to 1990, when the state directed toymakers to focus prominently on Christmas to satisfy popular export demand. Today only six producers of ring-turned toys remain. “Now it’s mostly decorative,” Dr. Auerbach said. “Toys for the parents. Less for the children.”

He had a point. By this time I had seen enough Seiffen ornaments to know they were meant to be admired, not grabbed by small fingers. Still, during my midweek visit, I also noticed how warmly the town welcomed families. Several workshops offer activities for kids, like creating an Advent wreath, or painting a toy train. Shops like the Handwerksmarkt sell craft supplies to make your own Christmas pyramid, or carve and paint a set of ring-turned animals. And I spotted many families of German tourists — they appeared to be mostly grandparents and grandchildren — exploring the toy village together.

A few miles outside of Seiffen, I thought I was still in Germany, but my cellphone had just welcomed me to the Czech Republic. I stood outside a plain, steeple-roofed house, looking at a small sign that read “Füchtner” and featured a nutcracker — it was the only clue I was in the right place.

I was here because of an offhand comment from Dr. Auerbach, the toy museum director. “The nutcracker,” he said, “was invented in Seiffen by Wilhelm Füchtner.” The nutcracker? I asked. The star of Tchaikovsky’s Christmas ballet? “Yes,” he said. “The family still produces them for export.”

He couldn’t offer an address, or any other information, but when I asked at my hotel, the woman at the front desk suggested I head south out of town on the Deutschneudorfer Strasse, a two-lane road. When I saw the sign, I pulled over.

A young woman answered my knock at the door. I didn’t have an appointment and I don’t speak German — but her face broke into a smile as soon as I uttered the words “nutcracker” and “Dr. Auerbach.” She ushered me into a bright workshop where half-painted nutcracker body parts were lined up with military precision. Her name is Carola Seiffert and she is one of five people employed at the family-owned Füchtner workshop.

Created by Wilhelm Füchtner in the 1870s, the Christmas nutcracker as we know it — that upright, clench-toothed toy soldier — “might have been inspired by Ernst Hoffmann’s story,” Ms. Seiffert said, referring to “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King,” which was published in 1816. “But also it was a form of satire.” Generally depicting an authority figure like a soldier, policeman or king, the nutcracker represented power — while the nut, cracked in its powerful jaws, symbolized the people. “It was a political joke,” she said.

Füchtner’s nutcrackers, carved from linden wood, their hair and beards created from scraps of rabbit fur, start at about 50 euros, or about $56, and the workshop also produces smoking men, or Räuchermänner: incense holders carved in the shape of little men, who puff smoke through their mouths. I found one such bearded chap, clad in green, irresistible. “He’s called the Ghost of the Woods,” Ms. Seiffert said. I bought him for 30 euros.

In fact, I found a lot of irresistible creations in Seiffen. I could have spent many hours at the workshops of Volkskunst or Richard Glässer, where the public is invited (for free at the former; with a modest fee of two euros at the latter) to observe the artisans as they glue small figures onto Christmas pyramids, for example, or meticulously paint nutcracker belts. And I could have spent many euros at the local galleries, especially Dregeno, the town’s cooperative of Erzgebirge arts and crafts, which sells the work of more than 120 artisans.

On my last morning in Seiffen, I walked up a hill to visit the Bergkirche, or mountain church. Built in 1776, the octagonal, steepled, butter-yellow structure is often depicted in Erzgebirge folk art.

Inside, the late-Baroque architecture created a sense of airiness; I half-listened to a German tour guide while I pictured the space at Christmas, ablaze with light and organ music. Lost in my thoughts, I left the church and promptly took a wrong turn, heading away from town.

When I turned, I saw pitch-roofed houses nestled in the valley and with a blink, imagined them covered with snow, candles shining from almost every window, glowing against the winter night. It was just like the Christmas village of my dreams.