Dr. C. Wayne Bardin, a groundbreaking researcher in reproductive physiology, who was instrumental in the development of long-acting contraceptive methods — like Norplant, Jadelle and Mirena — used by millions of women around the world, died on Oct. 10 at his home in Manhattan. He was 85.

His wife, Beatrice Bardin, confirmed the death without specifying a cause.

An endocrinologist, Dr. Bardin was passionate about finding ways for women to take control of their own health. While working for the nonprofit research organization the Population Council — as director of its Center for Biomedical Research and chairman of its International Committee for Contraception Research — he oversaw clinical trials in the mid-1990s that led to the approval of mifepristone, or RU-486, a synthetic steroid used as part of the so-called “abortion pill” to terminate a pregnancy.

When Dr. Bardin joined the Population Council in the late 1970s, the birth-control pill had been around for nearly two decades, but it provided only short-term contraception; women had to remember to take it regularly. And long-acting contraceptives, like intrauterine devices, or IUDs, which were developed in the early 1900s, were difficult to insert and remove and could have severe side effects. Many women who used them experienced cramps, infections and heavy bleeding.

One IUD, the Dalkon Shield, was linked in the 1970s to incidences of pelvic inflammatory disease and even death, casting a shadow over the entire market.

Dr. Bardin resolved to invest in new “bench to bedside” research — where the results of laboratory work are used directly on patients — to develop better contraceptive drugs and delivery systems.

“As much as he respected basic research, Dr. Bardin really wanted to see products that would change people’s lives come to fruition,” said James Sailer, the current executive director of the Center for Biomedical Research, in New York City.

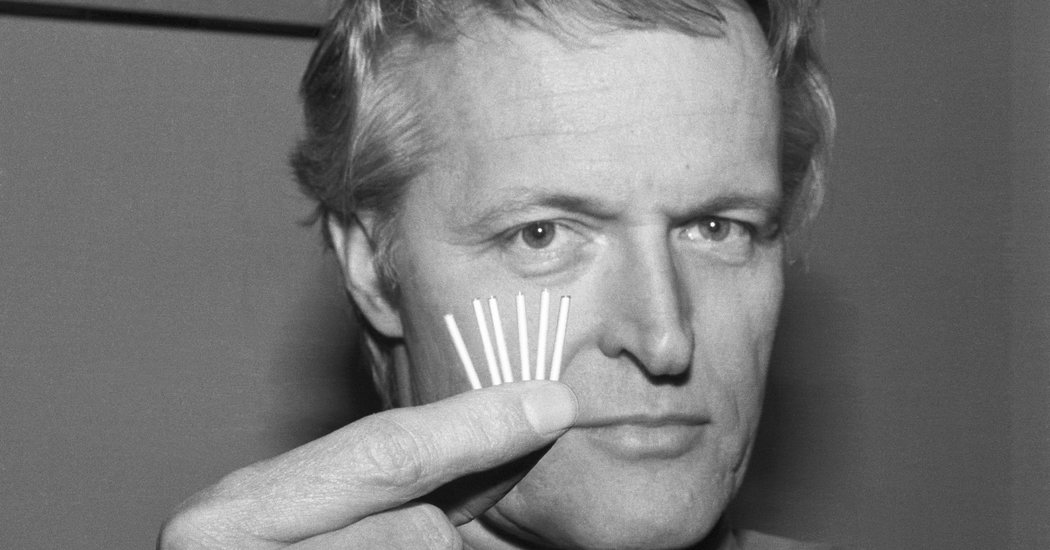

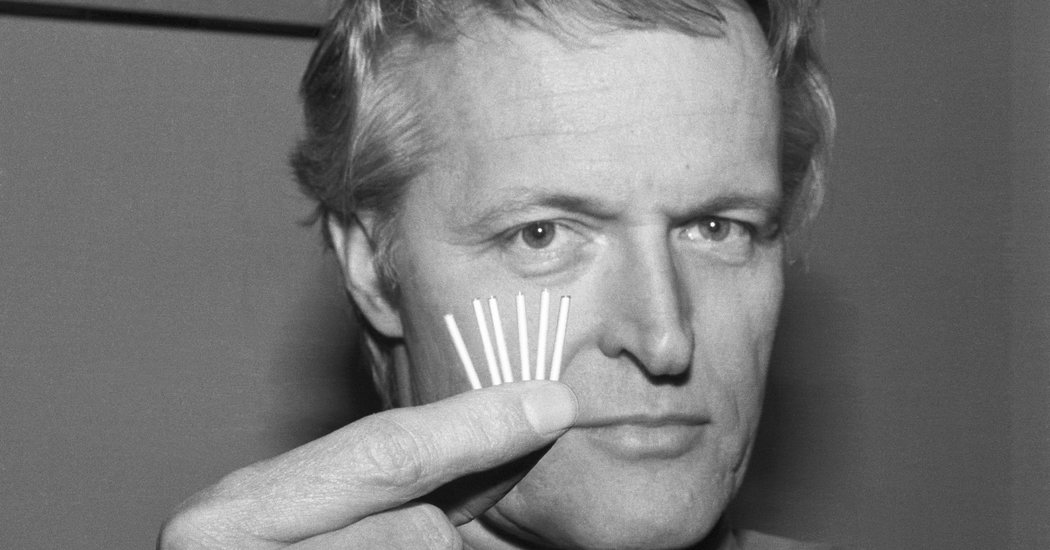

Dr. Bardin was part of a research team led by Sheldon J. Segal that developed Norplant, a tiny device in which six silicon rods the size of matchsticks, surgically implanted under the skin of the upper arm, release small amounts of the female hormone progestin every day. The hormone prevented pregnancy by thickening cervical mucus, making it impenetrable by sperm, and stopping the regular release of eggs for up to five years. It was one of the first significant advances in long-acting contraceptives since the Dalkon Shield disaster.

Introduced in 1991, Norplant was hailed as a welcome alternative to birth-control pills.

“Once it was put in, women didn’t need to remember to take medication every day,” Elizabeth Watkins, who studies the history of contraceptives at the University of California, San Francisco, said in a phone interview. “You could set it and forget it.”

But Norplant, too, turned out to have unwanted side effects. Some women complained of unpredictable bleeding, Dr. Watkins said; others experienced weight gain and hair loss. Many doctors and Planned Parenthood clinics declined to stock the device because of its cost ($365 per kit, plus about $500 more for the insertion — totaling, in today’s money, about $1,250). Moreover, they said, they could treat more women with birth-control pills, which presented fewer side effects.

From 1991 to 1994, legislators in many states proposed ways to incentivize the use of Norplant among welfare recipients, or even force them to use it, hoping that if women on welfare had fewer children, government costs would be reduced. None of these proposals became law, but the increasing controversy surrounding Norplant led its manufacturer, Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories (now Wyeth Pharmaceuticals) to take it off the market in 2002. It was never re-introduced.

Seeking a successor to Norplant, Dr. Bardin and his team developed an implanted delivery system manufactured by Schering Oy under the name Jadelle. Jadelle uses just two silicon rods, in contrast to Norplant’s six, to release a form of progestin. The federal Food and Drug Administration approved the device, initially as a means to prevent pregnancies for three years, a period that was later increased to five years, but in the wake of the Norplant controversy the manufacturer decided to market it only outside the United States.

A few years later another contraceptive device that Dr. Bardin and others developed at the Population Council was approved by the F.D.A. and introduced by Berlex Laboratories (now Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals) as Mirena, an IUD that emits a progestin for five years.

He also oversaw the development of Nestorone, a novel progestin that is released for up to a year through an easy-to-use vaginal ring, also developed by the researchers, that women could insert and remove themselves. The device was approved by the F.DA. under the brand name Annovera in 2018.

Dr. Bardin’s research for the Population Council also helped scientists understand how mifepristone, or RU-486, works to abort a pregnancy. A synthetic steroid, RU-486 blocks the action of progesterone and prompts the uterus to shed its lining. It becomes what is known as the “abortion pill” when used in combination with misoprostol, which causes contractions. The F.D.A. approved RU-486 in 2000.

Dr. Bardin paved the way for successful research into male contraceptives as well.

“There has been a lot of skepticism around whether men would ever use a contraceptive, but Dr. Bardin saw it as an obvious unmet need,” said Mr. Sailer, of the Center for Biomedical Research.

Developing male contraception has proved to be a challenge simply because men typically produce millions of sperm every day. But scientists at the Population Council built on Dr. Bardin’s research, combining Nestorone with the male hormone testosterone to develop a gel that suppresses sperm production while maintaining sexual drive. It is now being tested in human clinical trials.

Clyde Wayne Bardin was born on Sept. 18, 1934, in McCamey, Tex., to James Bardin and Nora Irene (Barnett) Bardin. In Houston, he graduated from Rice University with a bachelor’s degree in biology in 1957 and from what is now the Baylor College of Medicine in 1962.

After completing his medical internship and residency training at the New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center, Dr. Bardin joined the endocrinology research program at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md. In 1970, he was recruited to become chief of the Division of Endocrinology at Penn State University at Hershey. He joined the Population Council in 1978.

Dr. Bardin was at different times president of the Endocrine Society and president of the American Society of Andrology and received numerous awards. In his last decade he continued to work as a consultant for the Population Council and other organizations.

Dr. Bardin’s first marriage, to Bonnie Lambdin, ended in divorce in 1978. His second wife, Dr. Dorothy Terrace Krieger, died in 1985. In 1987 he married Beatrice Clement, who survives him, along with two daughters from his first marriage, Charlotte Merritt and Stephanie Torre; three stepchildren, Bryce MacDonald, Cybille MacDonald and Alexis Bormann; and six grandchildren.

Dr. Bardin and his wife enjoyed inviting colleagues and young researchers to dinner at their New York apartment, where conversation, stretching from medicine to culture to politics, could last for hours.

“Sitting next to him was the best seat in the house,” Stephanie Torre said of Dr. Bardin. “My dad was a tremendous conversationalist. He would focus all his attention on you and listen to you and show that he really cared about what you were talking about.”