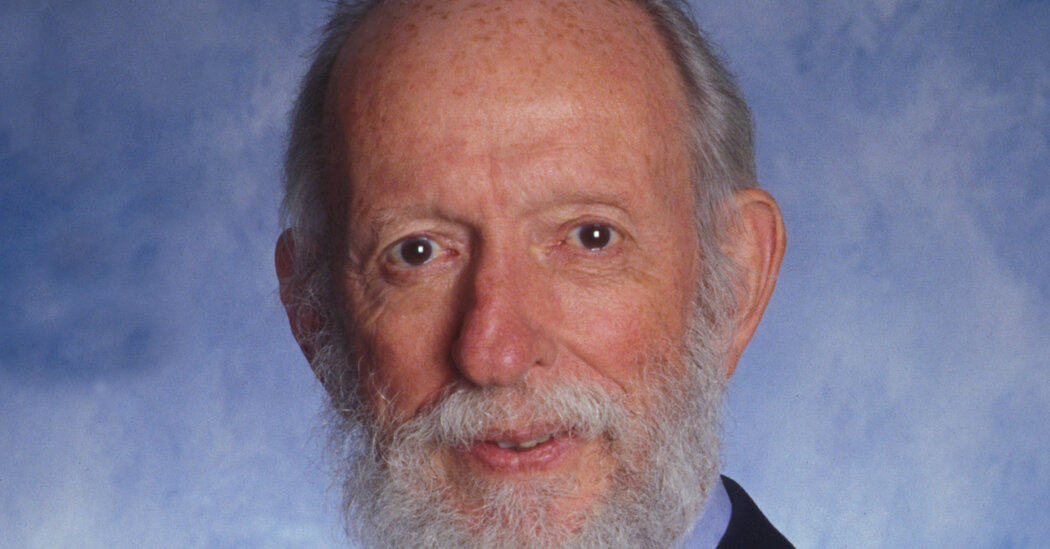

Dr. John A. Talbott, a psychiatrist who championed the care of vulnerable populations of the mentally ill, especially the homeless — many of whom were left to fend for themselves in the nation’s streets, libraries, bus terminals and jails after mass closures of state mental hospitals — died on Nov. 29 at his home in Baltimore. He was 88.

His wife, Susan Talbott, confirmed the death.

Dr. Talbott was an early backer of a movement known as deinstitutionalization, which pushed to replace America’s decrepit mental hospitals with community-based treatment. But he became one of the movement’s most powerful critics after a lack of money and political will stranded thousands of the deeply disturbed without proper care.

“The chronic mentally ill patient had his locus of living and care transferred from a single lousy institution to multiple wretched ones,” Dr. Talbott wrote in the journal Hospital and Community Psychiatry in 1979.

In a career of more than 60 years, Dr. Talbott held many of the leading positions in his field. He was president of the American Psychiatric Association; director of a large urban mental hospital, Dunlap-Manhattan Psychiatric Center, on Wards Island; chairman of the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland, Baltimore; and editor of three prominent journals: Psychiatric Quarterly, Psychiatric Services and The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease — which he was editing at his death.

Dr. Talbott exerted influence not as a researcher of the brain or neurological drugs but as a hospital leader, an academic and a member of blue-ribbon panels — including President Jimmy Carter’s Commission on Mental Health — and, especially, through prolific writings. A clear and muscular polemicist, he wrote, edited or contributed to more than 50 books.

“I admired him for taking the directorship of Manhattan State Hospital and his belief that psychiatrists should take the hard jobs and not just do private practice on the Upper West Side,” Dr. E. Fuller Torrey, a prominent psychiatrist and the founder of the Treatment Advocacy Center in Arlington, Va., said in an email.

In 1984, during Dr. Talbott’s presidency, the American Psychiatric Association released its first major study of the homeless mentally ill. The study found that the practice of discharging patients from state hospitals into ill-prepared communities was “a major societal tragedy.”

“Hardly a section of the country, urban or rural, has escaped the ubiquitous presence of ragged, ill and hallucinating human beings, wandering through our city streets, huddled in alleyways or sleeping over vents,” the report said. It estimated that up to 50 percent of homeless people had chronic mental illnesses.

Six years earlier, Dr. Talbott had published a book, “The Death of the Asylum,” which railed against both the broken system of state hospitals and the broken policies that replaced them.

In an interview with The New York Times in 1984, he acknowledged that psychiatrists who had championed community-based treatment as an alternative to institutions, including himself, bore part of the blame.

“The psychiatrists involved in the policymaking at that time certainly oversold community treatment, and our credibility today is probably damaged because of it,” he said.

In an account of Dr. Talbott’s career submitted to a medical journal after his death, a former colleague, Dr. Allen Frances, wrote, “Few people have ever had so distinguished a career as Dr. Talbott, but perhaps none has ever had a more frustrating and disappointing one.”

Dr. Frances, the chairman emeritus of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University, explained in an interview that Dr. Talbott had been a leader in the field of “community psychiatry,” which held that mental illness was influenced by social conditions — not just a biological disposition — and that treatments required taking into account a patient’s living conditions and the range of services available.

Community psychiatry was supposed to be the alternative for patients no longer warehoused in run-down, often abusive state hospitals. A new generation of drugs held promise that patients could live at least semi-independently.

“They were working hard to get psychiatry to be less stodgy, less biological, less psychoanalytical and more socially and community oriented,” Dr. Frances said of Dr. Talbott and others who championed community psychiatry.

But the high hopes for robust outpatient treatment in community settings were never adequately realized. The Community Mental Health Act, a 1963 law championed by President John F. Kennedy, envisioned 2,000 community mental health centers by 1980. Fewer than half that many had been opened by then, as funding failed to materialize or was diverted elsewhere.

At the same time, deinstitutionalization cut the number of patients in state hospitals by 75 percent, to fewer than 140,000 in 1980 from 560,000 in 1955.

“The disaster occurred because our mental health delivery system is not a system but a nonsystem,” Dr. Talbott wrote in 1979.

John Andrew Talbott was born on Nov. 8, 1935, in Boston. His mother, Mildred (Cherry) Talbott, was a homemaker. His father, Dr. John Harold Talbott, was a professor of medicine and an editor of The Journal of the American Medical Association.

In 1961, Dr. Talbott married Susan Webster, who had a career as a nurse and hospital administrator, after the couple met during intermission at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

Along with his wife, Dr. Talbott is survived by two daughters, Sieglinde Peterson and Alexandra Morrel; six grandchildren; and a sister, Cherry Talbott.

He graduated from Harvard College in 1957 and received his M.D. from the Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1961. He did further training at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital/New York State Psychiatric Institute and the Columbia University Center for Psychoanalytic Training and Research.

Drafted during the Vietnam War, he served as a captain in the Medical Corps in Vietnam in 1967 and 1968. He received a Bronze Star for persuading troops to take their malaria pills.

“The reason they weren’t taking them was because a case of malaria was a ticket home,” he later explained. “Then I scared the hell out of them by showing them examples of what malaria could lead to.”

Once he was home, Dr. Talbott became active in the antiwar movement. He was a spokesman for Vietnam Veterans Against the War at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The next year he helped organize a protest at Riverside Church in Manhattan in which the names of soldiers killed in Vietnam were read aloud by a procession of speakers, including Edward I. Koch, Leonard Bernstein and Lauren Bacall.

After retiring as chairman of psychiatry at the University of Maryland in 2000 after 15 years, Dr. Talbott indulged a lifelong appreciation for fine dining by contributing to online food sites. In 2006, he began a blog, John Talbott’s Paris, in which he chronicled meals he ate on frequent visits to the French capital.