A half-century ago, when researchers said cancers were caused by exposure to toxins in the environment, Dr. Henry T. Lynch begged to differ.

Many cancers, he said, were hereditary. To prove his point he traveled to gatherings of families that he suspected had histories of hereditary cancer. He arranged to meet family members and asked: Who in the family had cancer? What kind of cancer? Could he get medical records, and blood samples, which he could freeze and store?

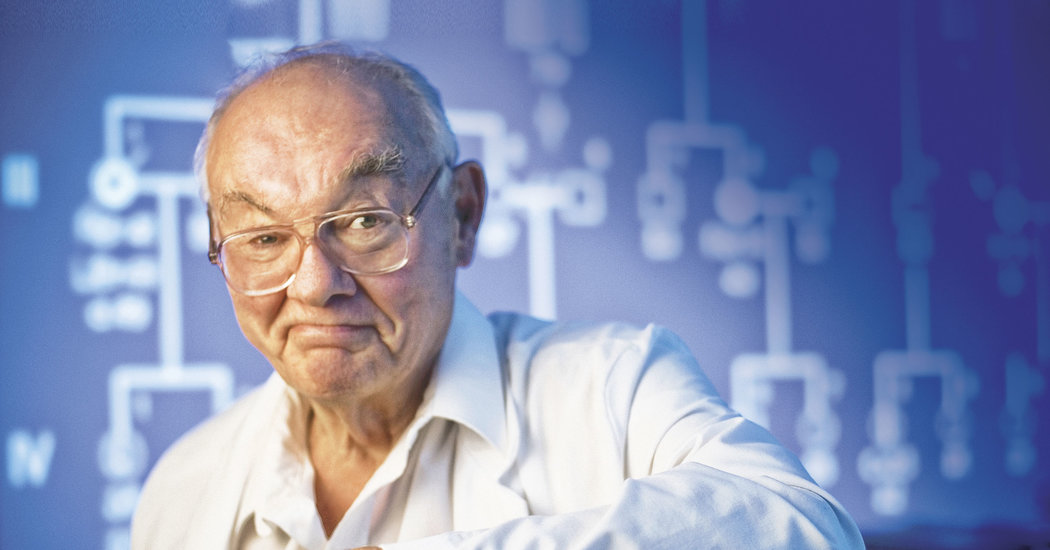

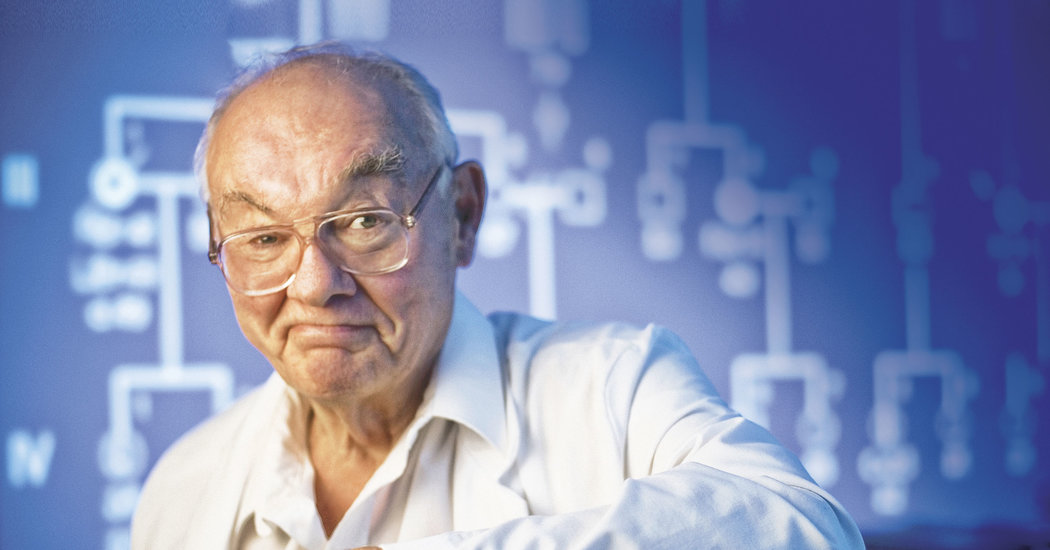

He hand-drew family trees, with squares for men and circles for women, marking who got cancer and what kind. He was soon insisting to a doubting world that he had found compelling evidence of genetic links.

In time, the medical world accepted his claims, and his work — the family trees, the blood samples — eventually contributed to the discovery, by others, of a gene that when mutated can lead to colon cancer and an array of other cancers. He also contributed work that led to the discovery of gene mutations that greatly increase the risk of breast and ovarian cancer.

Dr. Lynch died on June 2 at Bergan Mercy Hospital, the main teaching hospital for Creighton University in Omaha, where he had spent most of his career. He was 91. His son, Dr. Patrick M. Lynch, a gastrointestinal endoscopist at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, said the cause was congestive heart failure.

Dr. Henry Lynch, a 6-foot-5 former professional boxer whose physical presence belied his gentle nature, was an old-fashioned researcher who never changed his ways.

Investigators like to talk about translational research, going from bench to bedside — making discoveries in the lab and using them to treat patients. Dr. Lynch went in the opposite direction, from bedside to bench, said Dr. Funmi Olopade, director of the center of clinical cancer genetics at the University of Chicago. In Dr. Lynch’s case, though, others took over the bench part.

For years, epidemiologists dismissed Dr. Lynch’s data as anecdotal, said Dr. Steven Narod, who runs the family cancer unit at Women’s College Hospital in Toronto. Skeptics argued that the cancers Dr. Lynch saw could have occurred by chance. They included common cancers, like those of colon, breast and thyroid, which can occur in almost any family.

But some medical professionals, including Dr. Narod, were convinced even without the statistical analyses. “In 1987, I looked at those family trees and said, ‘I’m in,’ ” he said.

Dr. Olopade met Dr. Lynch in Omaha in 1992, when she wanted to search for breast cancer genes. Dr. Lynch offered his data.

“That day stood out in my memory,” she said. “He gave me every questionnaire, every consent.”

Dr. Judy Garber, chief of the division of cancer genetics and prevention at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, said Dr. Lynch had helped her, too. “He was among the most decent people in academics,” she said.

Cancer researchers now estimate that 5 to 10 percent of cancers are inherited. Hereditary cancer syndromes, like the ones Dr. Lynch investigated, include gene mutations that predispose some to more common cancers.

One form of hereditary cancer is often called Lynch syndrome (it is also known as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer, or HNPCC) because Dr. Lynch first identified families in which it occurs. People with Lynch syndrome have a higher risk of certain types of cancer.

Dr. Lynch liked to tell the story of how he got interested in cancer genetics:

When he was a medical resident, he saw a patient who was dying of colon cancer. The man began telling Dr. Lynch about all the other people in his family who had had cancer. Intrigued, Dr. Lynch applied for a research grant from the National Institutes of Health, hoping to show that colon cancer could be hereditary. He was turned down.

Undaunted, he persisted, collecting pedigrees, drawing family trees and eventually getting research grants. He mostly counseled cancer patients, advising them rather than directly caring for them, his son said.

Henry Thompson Lynch was born on Jan. 4, 1928, in Lawrence, Mass., to Henry and Eleanor Lynch. He grew up poor on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. His father, a salesman, lost his job in the Depression, and his mother was a secretary.

With the onset of World War II, Henry enlisted in the Navy at age 15, using the name of a relative a few years older. He was shipped to the South Pacific as a gunner and sustained permanent hearing loss from the guns’ blasts.

When he returned from the war he earned a high school equivalency degree and became a boxer, competing under the name Hammerin’ Hank.

After a few of years of boxing professionally, he enrolled at the University of Oklahoma in Norman. After graduating in 1951, he received a master’s degree in clinical psychology from the University of Denver the next year. At the time, his son said, Dr. Lynch wanted to find the genetic roots of schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders.

Then he decided to become a medical doctor. He later explained to his son that he had concluded that physicians had an assured income and more career options than scientists with Ph.D.s.

He earned his medical degree at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston in 1960, after completing all the coursework toward a Ph.D. in human genetics at Austin.

Hired by Creighton in 1967, he stayed there because, his son said, as a serious Roman Catholic he liked being at a Jesuit institution. Dr. Lynch founded the Hereditary Cancer Center at the university in 1984.

In addition to his son, Dr. Lynch is survived by his daughters, Kathy Pinder and Ann Kelly; two brothers, Warren and Donald; 10 grandchildren; and nine great-grandchildren. His wife, Jane (Smith) Lynch, died in 2012.

Dr. Lynch was buried in a cemetery across the street from the Creighton hospital, in view of a sign on the building that says “The Henry Lynch Cancer Center.”