The David Kordansky Gallery has mounted a wonderful wormhole of an exhibition, “Doyle Lane: Weed Pots.” Its point of access is the small unassuming “weed pot,” a frequent accent in modern California interiors starting in the late 1950s. Thrown on a wheel, Lane’s pots were rarely more than 3 or 4 inches high, spherical or elliptical in volume and usually topped by a short, narrow neck, small mouth and turned lip, designed to hold a dried sprig of weed.

From this seemingly modest beginning, Lane (1923-2002), who was African American, created a dazzling universe of color, shape, texture and proportion. He also made ceramic tile, pendant jewelry, paintings and murals, but the “weed pot” is his signature. Kordansky’s generous display of 100 pots is Lane’s first solo show in New York. It is also a refresher course in close looking, and reminder of the power of form.

Lane didn’t invent the “weed pot,” but as this exhibition proves, he perfected it. It was his stage. From its confines, he unfurled his miraculous glazes, working alone with two small kilns in his studio in El Sereno in East Los Angeles. One of the greatest here has an almost timeless quality; it could be archaic, just unearthed in Peru or China, but it is also contemporary. It features a double glaze: a light matte green underglaze and on top, a brittle yellow glaze, almost translucent, that blisters during the firing process, creating holes that expose the green.

The show has been organized by the Australian-born, Los Angeles-based sculptor Ricky Swallow, who discovered Lane’s pots in an antiques mall in Pasadena in 2010. Swallow curated a smaller, similarly installed iteration for Kordansky’s Los Angeles home base in 2020. The installation is luxurious: The pots are lined up in single rows of 14 in each of seven vitrines in plenty of space. Walk along both sides of the vitrines and you’ll see every piece fully in the round. And while the accompanying catalog may not be the monograph the artist deserves, it is the biggest yet and contains a great deal of information about him and his milieu.

Doyle Lane (1923-2002) was born in New Orleans and came to Los Angeles in 1946. He studied ceramics at East Los Angeles City College and at the University of Southern California, and to his great fortune, got a coveted job as a glaze technician for the industrial chemical company L.H. Butcher, where he worked for eight years. There Lane formulated and tested hundreds of different glazes, gaining experience and a body of knowledge that few other postwar artist-potters possessed.

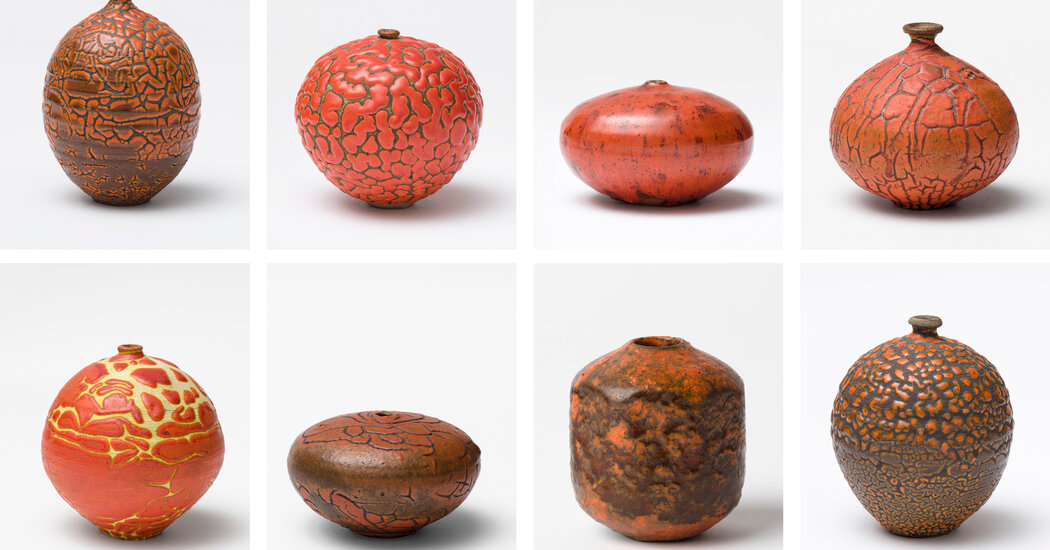

In this show two areas of special interest are evident: one is a passion for red and orange glazes, which are used on nearly a third of the pots here. The other is an expert cultivation of chance in the glaze firing to encourage the imperfections of either cracking, originally pursued most intently by Chinese and Koreans potters, or the less familiar effects of crawling. This occurs when a thick glaze contracts during firing into separate little islands on the exposed clay, which Lane often stained with yellow or ocher for greater contrast.

In some pots, it appears that cracking and crawling might converge, as with an orange glaze on an ocher-stained pot. The glaze contracted without exposing much clay, bunching up into a kind of dense-packed low relief and a pattern that suggests entrails.

His glazes feel experimental, yet he always seemed to know what he was doing. Swallow said in a phone call that Lane used his kiln like an instrument, understanding how placement in a kiln could affect the outcome and knowing when to interrupt a firing that was getting ahead of itself.

The small size of these vessels fulfilled several needs, foremost was the desire to live off his work, which he did. They used his small kilns efficiently and were easy to transport. Lane had only a few gallery shows in Los Angeles — and none anywhere else. He sold his pots from showrooms he built adjacent to his studio, at craft fairs and occasionally door to door. (Lane was determined to, and largely successful at, living off his work.)

But the primary function of small size was aesthetic: Lane excelled at compression, making something small seem big. Small size meant that encounters with his pieces were up close and in full, granular. After Lane’s glazes, the most interesting aspect of this coming-together of so many of the “weed pots” is the way they reveal his sensitivity to shape, weight and volume. Pots with round silhouettes are sometimes as round as softballs. But usually their volumes have gentle swells either above or below, which communicates a quietly animating balance.

Lane once said that many of his colors did not exist until he figured out how to make them. Their originality is just one way that his weed pots surpassed craft to become art. They form a historical high point that reaches across mediums and cultures. They are period pieces that have outlived their period.

Doyle Lane: Weed Pots

Through Aug. 4, David Kordansky Gallery, 520 West 20th Street, Manhattan; davidkordanskygallery.com; 212-390-0079.