More than 3 million Americans live with disabling brain injuries. The vast majority of these individuals are lost to the medical system soon after their initial treatment, to be cared for by family or to fend for themselves, managing fatigue, attention and concentration problems with little hope of improvement.

On Saturday, a team of scientists reported a glimmer of hope. Using an implant that stimulates activity in key areas of the brain, they restored near-normal levels of brain function to a middle-aged woman who was severely injured in a car accident 18 years ago.

Experts said the woman was a test case, and that it was far from clear whether the procedure would prompt improvements for others like her. That group includes an estimated 3 million to 5 million people, many of them veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, with disabilities related to traumatic brain injuries.

“This is a pilot study,” said Dr. Steven R. Flanagan, the chairman of the department of rehabilitation medicine at NYU Langone Health, who was not part of the research team. “And we certainly cannot generalize from it. But I think it’s a very promising start, and there is certainly more to come in this work.”

The woman, now in her early 40s, was a student when the accident occurred. She soon recovered sufficiently to live independently. But she suffered from persistent fatigue and could not read or concentrate for long, leaving her unable to hold a competitive job, socialize much, or resume her studies.

She and her family asked to remain anonymous, and the researchers did not reveal further details other than to remark on her improvement.

“Her life has changed,” said Dr. Nicholas Schiff, a professor of neurology and neuroscience at Weill Cornell Medicine and a member of the study team. “She is much less fatigued, and she’s now reading novels. The next patient might not do as well. But we want keep going to see what happens.”

A lack of research funding and interest has made that difficult, he added. “We’ve not been able to do so because there’s an incredible drag on doing anything for this population,” he said

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

Dr. Schiff and another team leader, Dr. Joseph T. Giacino, director of rehabilitation neuropsychology at Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital and an associate professor at Harvard Medical School, presented the case at a brain-science convention in Washington, D.C., in an informal, public session.

The two collaborated with clinical centers at Stanford and the University of Utah, and with researchers at the Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Jaimie M. Henderson, a neurosurgeon at Stanford, performed the surgery, and the team is recruiting other candidates in the Bay Area to see if the procedure is viable for other people with mild to moderate traumatic brain injuries.

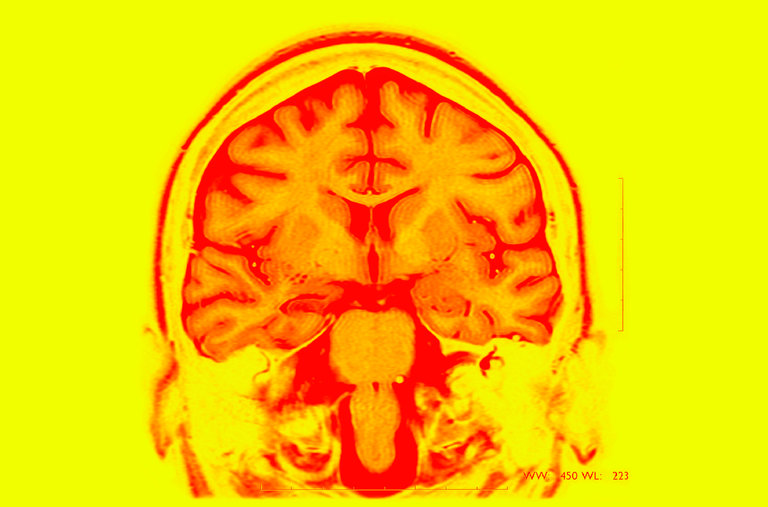

In the operation, performed last summer, Dr. Henderson threaded two electrodes into the thalamus, a switching center deep in the brain. Precision was critical. Before the surgery, the team did extensive work to identify specific regions in the brain that support activation of the frontal cortex, which is involved in thinking and planning, and the basal ganglia, which supports learning and memory.

“Operating on the thalamus is pretty routine,” Dr. Henderson said in an email. “This is a different target, though, and difficult to hit because of its size and shape. So a bit of extra precision is called for.”

The electrodes were connected to a pacemaker device, implanted in the woman’s chest wall, that produced active current for 12 hours a day, from morning to evening.

The woman improved gradually, and by three months was consistently scoring about 15 percent better than she had previously on standardized tests of attention, planning and executive function. She also reported 70 percent less fatigue on a standard measure, and no longer took daily afternoon naps, as she had before, the researchers reported.

At one point during her rehabilitation, the pacemaker accidentally failed, and her gains tapered off. Doctors quickly restored the current, and her ability improved.

About one in five people with similar injuries receive some continuing treatment. This often includes cognitive therapy — typically, computer-based training for attention and memory, an hour a week for 12 weeks — and many see gradual improvements. But that therapy is not easy to access, and insurers don’t always pay for it.

“Getting a 10 percent improvement is considered excellent, and they broke right through it to 15 percent,” said Dr. Joseph Ricker, director of psychology at NYU’s Rusk Rehabilitation center.

In 2006, members of the same research team performed a similar operation on a 38-year-old man with severe brain damage; he was living in a partially conscious state, only periodically aware and virtually mute and immobile. The procedure allowed him to recover some movement and speech, gains he maintained until his death some years later. But no similar procedures have been reported since then, the researchers said.

One challenge to developing new treatments for traumatic brain injuries is that candidates are hard to find. “We are targeting here the heart of the problem, mild to moderate traumatic brain injury,” Dr. Giacino said. “But finding people and accessing them is difficult. They are really isolated.”

Dr. Flora Hammond, who leads the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Department at Indiana University School of Medicine, said: “Recovery from these deficits is challenged by a sparsity of proven treatments and lack of access to rehabilitative care. These observations are a positive step toward improving life after brain injury.”