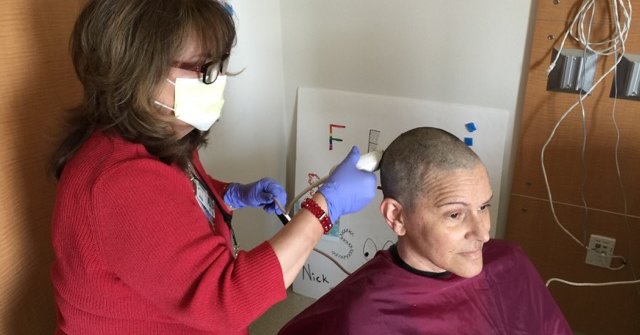

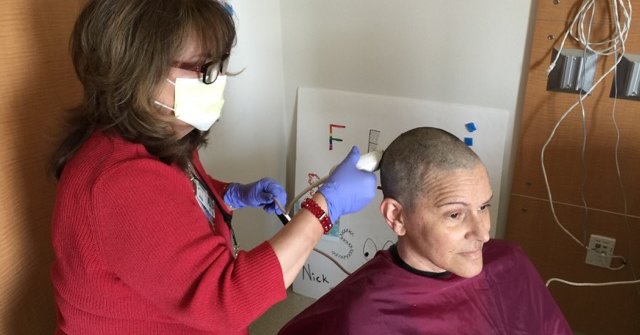

The razor had a familiar thrum. Only this time, I wasn’t the one doing the shaving. I was watching as my sister’s remaining hair fell away.

She was putting on a brave face, joking with the hairdresser. Her defiant look said: “Leukemia’s not going to get me.” But in her eyes, I also saw terror. I wanted to rescue her, but there was nothing I could do.

Eighteen months younger than me, Victoria had always been there, someone I took for granted. When we played as children, she tried to keep up, to convince me she was cool and worthy of attention. We had weathered much together: a move to London, our parents’ divorce, a health crisis of my own. She always had my back. But with college, marriages, moves across the country, kids of our own, we grew apart. She became an actress; I became a neurosurgeon.

Was our relationship still relevant? Victoria had pushed many visitors away, but invited me to fly out from North Carolina to spend a week at her bedside at City of Hope, the cancer hospital outside Los Angeles where she was being treated. As I entered her hospital room for the first time, I was afraid I would disappoint her.

I was in a strange city, in an unknown place, asking for directions and permission to enter restricted areas. I had to scrub my hands, glove and gown to enter her room, a ritual I perform many times in the course of a busy workday but one that felt foreign and awkward in this new context.

But Victoria and I grinned at each other through our masks, and her eyes twinkled with the pleasure of a long-anticipated reunion. The years of distance vanished. She gave me courage, which was strange, because I thought I was there to give her courage. While we spoke about the medical facts of her illness during that glorious first week, mostly we chatted, sharing memories of our childhood, played Yahtzee and Scrabble, watched movies contending for Oscars and laughed.

I stayed each day by her bedside, leaving only to eat and take walks around the hospital’s gardens while she rested, then spent the afternoon and evenings with her as well. I came back for another week after her bone marrow transplant to be with her while she recovered, fighting through fevers, chills, vomiting and diarrhea, seemingly endless tests and intravenous treatments. She was fearless as she prepared for the transplant, enduring full-body radiation and powerful chemotherapy given to kill off her marrow in preparation for an infusion of stem cells (from her son, Nick, who became her donor).

Each day they weighed her and, despite eating nothing at all, she was gaining, rather than losing, weight. She was furious: She had hoped at least she would be thinner after all she was going through.

I felt my sister’s frustration and anguish as we waited hours for doctors and consultants to come by and answer our questions. Stripped of my physician status, I was aware of the consuming and unrelenting fear that patients carry with them and cannot shake. I was no longer the doctor dropping in on rounds, calling the shots.

While Victoria wouldn’t discuss her mortality with anyone (that was off the table), she resolved herself to conquer whatever the medical team asked of her. Each day she walked further, sat in a chair longer, tried to eat when she could keep things down. The housekeepers stopped by to talk with Victoria every morning. She knew their names, and the names of their children. José spoke of his son’s difficulties with school. Victoria listened and made suggestions. She knew the nurses’ names and concerns as well; how long their commutes were, how they tried to balance the personal and professional demands in their lives.

Over time, Victoria became increasingly grateful for the kindness and compassion of others, whether it came from her husband, Pat, who stayed with her each day (my visits provided necessary respite for him); or from her sons, Nick and Will, whose faces beamed at her from large poster-size photos they had placed in her room; or from the friends who looked after her family, feeding them every day for the eight-plus months of her continuous hospitalization.

Sitting with Victoria allowed me to reconnect with a part of myself I had been suppressing for years. Her courage rubbed off on me. Blood test results set the expectations for each new day. A higher white blood count would allow Victoria the freedom to step from her room into the hallway to take a few steps around her unit, albeit with a thick filtration mask covering her mouth and nose. If her counts were low, she would sit confined to her room, often for days on end, gazing longingly through a sealed window at people six stories below walking the garden paths and at the trees swaying in the breeze.

I went to City of Hope to support my sister, and what I found there was gratitude: appreciation for others; reveling in small pleasures we usually take for granted, like a hot shower, sunlight, a walk outdoors.

Victoria’s gift was a tangible lesson, something I have been able to carry with me. Now I approach patients differently than I did before her illness.

Recently, I met Meghan White, a 34-year-old woman with breast cancer that had metastasized to her brain. I was initially hesitant and fearful as I entered the examining room to see her one afternoon after a long day in clinic. She was going to need me to surgically place a reservoir into her brain to deliver chemotherapy. My colleagues and I also planned to perform focused radiation treatments to two tumors in her brain that were growing quickly. Meghan sat bald and proudly beautiful in my examining room, her mother there to support her.

Previously, I would have thought nothing of her shaved head, but now I understood Meghan had a story to tell. As they were with Victoria, the odds were long against her.

Meghan was a fourth-grade teacher and wanted to put off her surgery until her students completed their year-end assessments late the following week. I agreed that it was a milestone she shouldn’t miss and said we could work around her schedule. I held her hand. Her mother, eyes brimming with tears, asked me to take care of her baby. I assured her I would.

As I left the room, Meghan thanked me and said this was the first doctor’s appointment she had had in a long time where she didn’t cry. I never used to cry when speaking with patients. I would gird myself, push forward, distract myself with new and pressing problems to fix; I focused on technical, rather than human, matters. Now, I told Meghan that I would cry for us both. My sister was present in that room, in the patient sitting before me and in the way I was newly able to comfort and reassure her.

With Victoria, as with Meghan, my immediate reaction to her diagnosis had been fear and a desire to run (or at least to hide from the depths of my feelings while still being physically present). But in witnessing Victoria’s fearlessness, and later her gratitude, I found courage. My sister showed me how to become a better brother and, at the same time, a better doctor.

Joseph Stern is a neurosurgeon in Greensboro, N.C., who has written a memoir about the loss of his sister.