Pancreatic cancer has a bad reputation. It is a terrible disease, but most people do not realize there are ways that early detection can help.

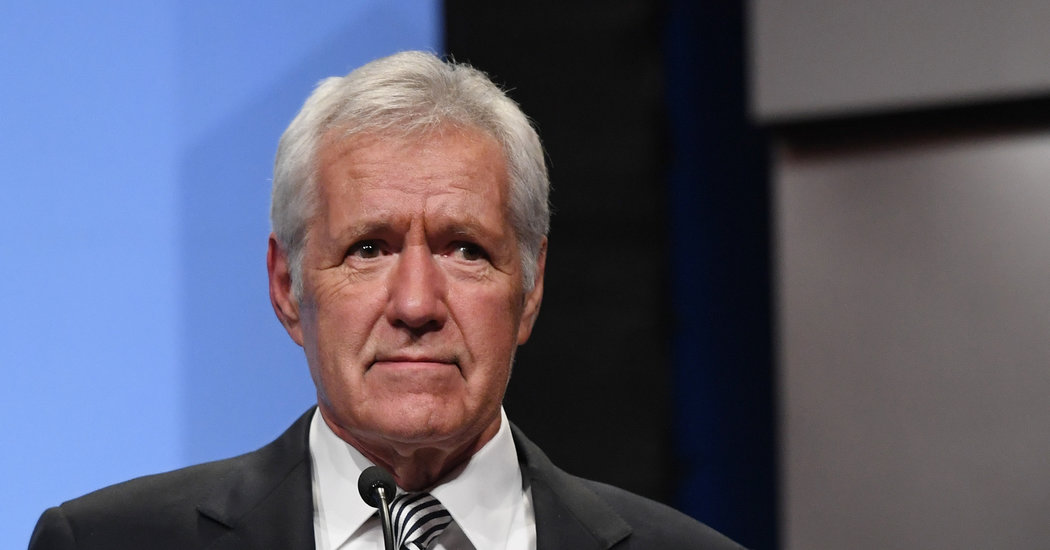

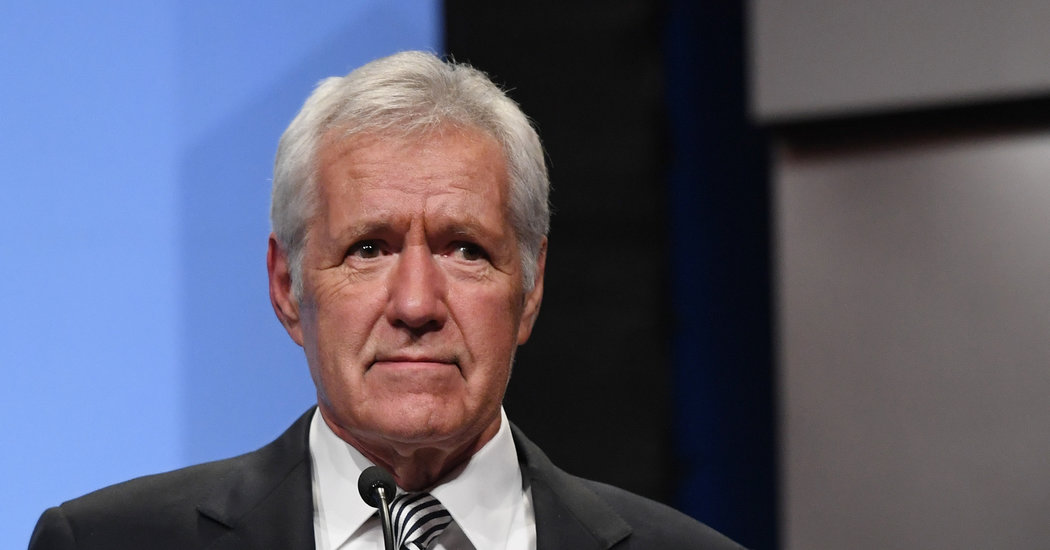

When the “Jeopardy!” host, Alex Trebek, announced last week that he had Stage 4 pancreatic cancer, many people assumed that it was an automatic death sentence.

Not Mr. Trebek.

“I plan to beat the low survival rate statistics for this disease,” he said in a video. “Truth told, I have to. Because under the terms of my contract, I have to host ‘Jeopardy!’ for three more years.”

He was trying to stay positive. But the more prevalent grim outlook even affects some doctors. Not long ago, an officer of the American Cancer Society said that there was no standard screening test for pancreatic cancer that is proven to save lives, noting that CT scans, which could help detect early cancers, carry risks of their own.

But there are some less risky steps that may help you avoid getting pancreatic cancer.

First, know your risk. Insist that your physician do a thorough and smart family history. If more than one person in your family has had pancreatic cancer, you should have your DNA examined in what we call a germ line test. The cost of germ line testing has plummeted in the past few years. If it is not covered by insurance, the out-of-pocket cost is now about $250. A sample of blood will tell you if a relevant mutation is present in all cells in the body.

It will reveal whether you have a high enough risk of the disease that you should have annual pancreatic screening, typically covered by insurance — either an M.R.I. or a special kind of endoscopy called an endoscopic ultrasound, also called an EUS.

If you have one of the BRCA genes that suggests a higher risk for pancreatic cancer, you should consider further testing; another sign of higher risk is the presence of melanoma and pancreatic cancer in one family.

We have tended to underestimate the importance of genes in conferring risk. Too many people misunderstand genetic screening. They think that mutations in the BRCA gene are common only in people of Jewish ancestry and relate only to breast and ovarian cancer. In fact BRCA mutations are present in many ethnic groups and greatly increase the risk not only of breast and ovarian cancers, but also of pancreatic cancer.

In the N.Y.U. pancreatic cancer clinic I run, we are performing germ line DNA testing on all pancreatic cancer patients, and we have found that 15 percent had a germ line mutation that probably contributed to their risk of developing the disease. Knowing that helps us tailor the treatment and helps identify siblings and children who might be at higher risk.

For half the patients with pancreatic cancer who come to my clinic, I can’t identify a known risk factor. Risk factors we can control include smoking, drinking, obesity and Type 2 diabetes, which doubles the risk.

Right now, pancreatic cancer is a relatively rare disease but the third leading cause of cancer deaths, because so few people survive. We aim to change that. We know we can help people at risk, but it is much more challenging if most people think that prevention and early detection are impossible.

Screening of those at high risk is of demonstrated value. New studies show that if you screen someone and find something, the odds that you can do surgery are 80 to 90 percent. Most of those who do not get help until symptoms arise are unable to have lifesaving surgery. Without surgical resection, there is little hope of long-term survival. For all patients, the five-year survival rate is only 9 percent.

But new chemotherapy regimens have helped patients live longer, and a few patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer in clinical drug trials have had long-term survival.

Of course, we still need more ways to find this cancer earlier and better clinical trials to bring new, more effective therapies to patients. Pharmaceutical companies are trying to find new drugs for this disease, but they often will not pay for tumor biopsies at the beginning, middle and end of trials. These biopsies are the only way to learn why certain drugs are working and others are not.

This is a tough cancer that not enough people have wanted to study, one that until recently didn’t receive much research funding. Cases of high-profile patients like Mr. Trebek help draw attention to the disease, but it’s also important to remember cases like that of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who had surgery for pancreatic cancer in 2009. She reportedly had no symptoms, but her cancer was found during a routine CT scan.

Those at increased risk should know that screening and genetic testing can help save their lives.

Dr. Diane M. Simeone is director of the Pancreatic Cancer Center at New York University Langone Health.