WASHINGTON — It took only one question — the very first — in Tuesday night’s Democratic presidential primary debate to make it clear that the issue that united the party in last year’s congressional elections in many ways now divides it.

When Jake Tapper of CNN asked Senator Bernie Sanders whether his Medicare for All health care plan was “bad policy” and “political suicide,” it set off a half-hour brawl that drew in almost every one of the 10 candidates on the stage. Suddenly, members of the party that had been all about protecting and expanding health care coverage were leveling accusations before a national audience at some of their own — in particular, that they wanted to take it away.

“It used to be Republicans that wanted to repeal and replace,” Gov. Steve Bullock of Montana said in one of the more jolting statements on the subject. “Now many Democrats do as well.”

Those disagreements set a combative tone that continued for the next 90 minutes. The health care arguments underscored the powerful shift the Democratic Party is undergoing, and that was illustrated in a substantive debate that also included trade, race, reparations, border security and the war in Afghanistan.

In the end, it was a battle between aspiration and pragmatism, a crystallization of the struggle between the party’s left and moderate factions.

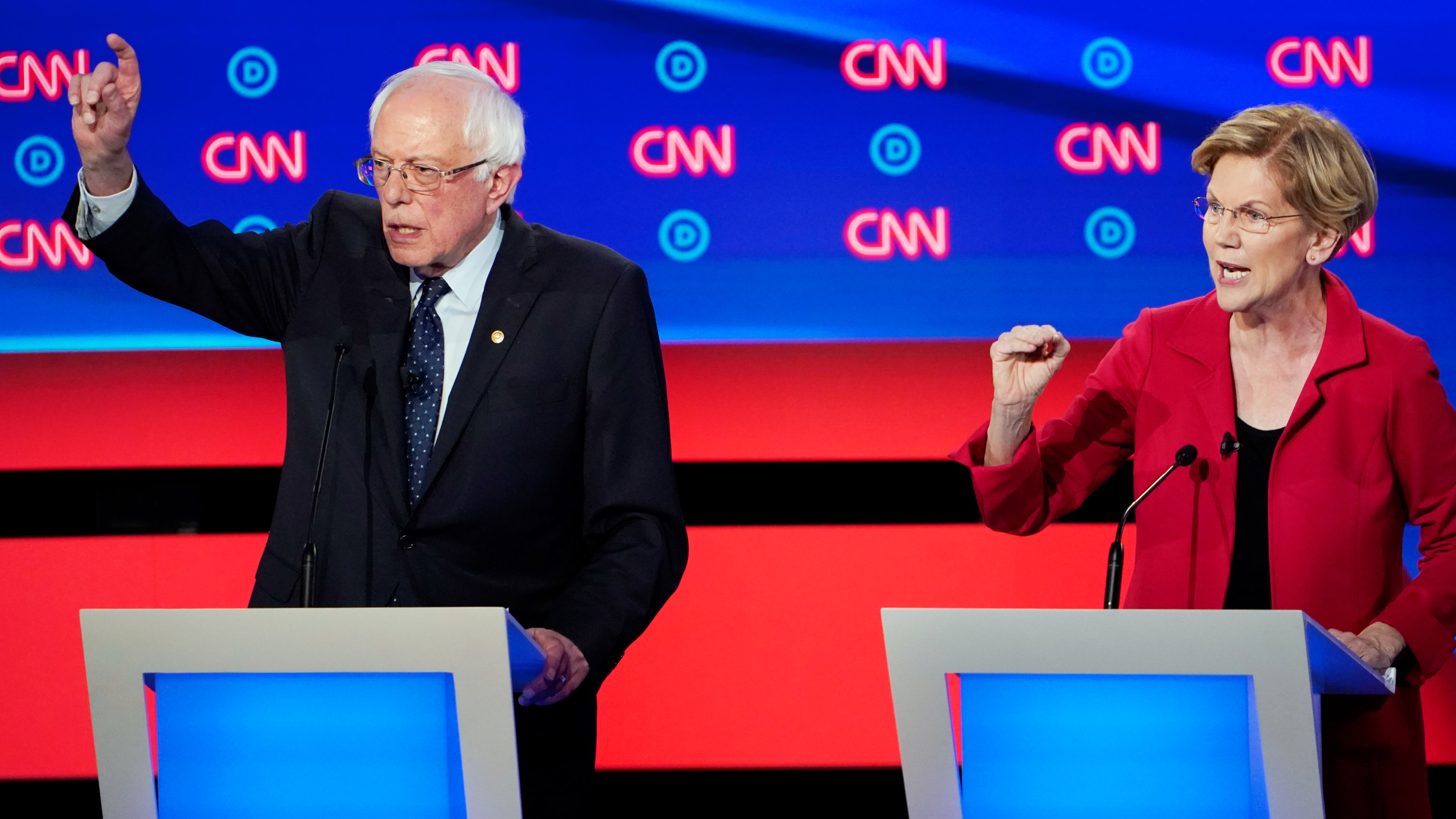

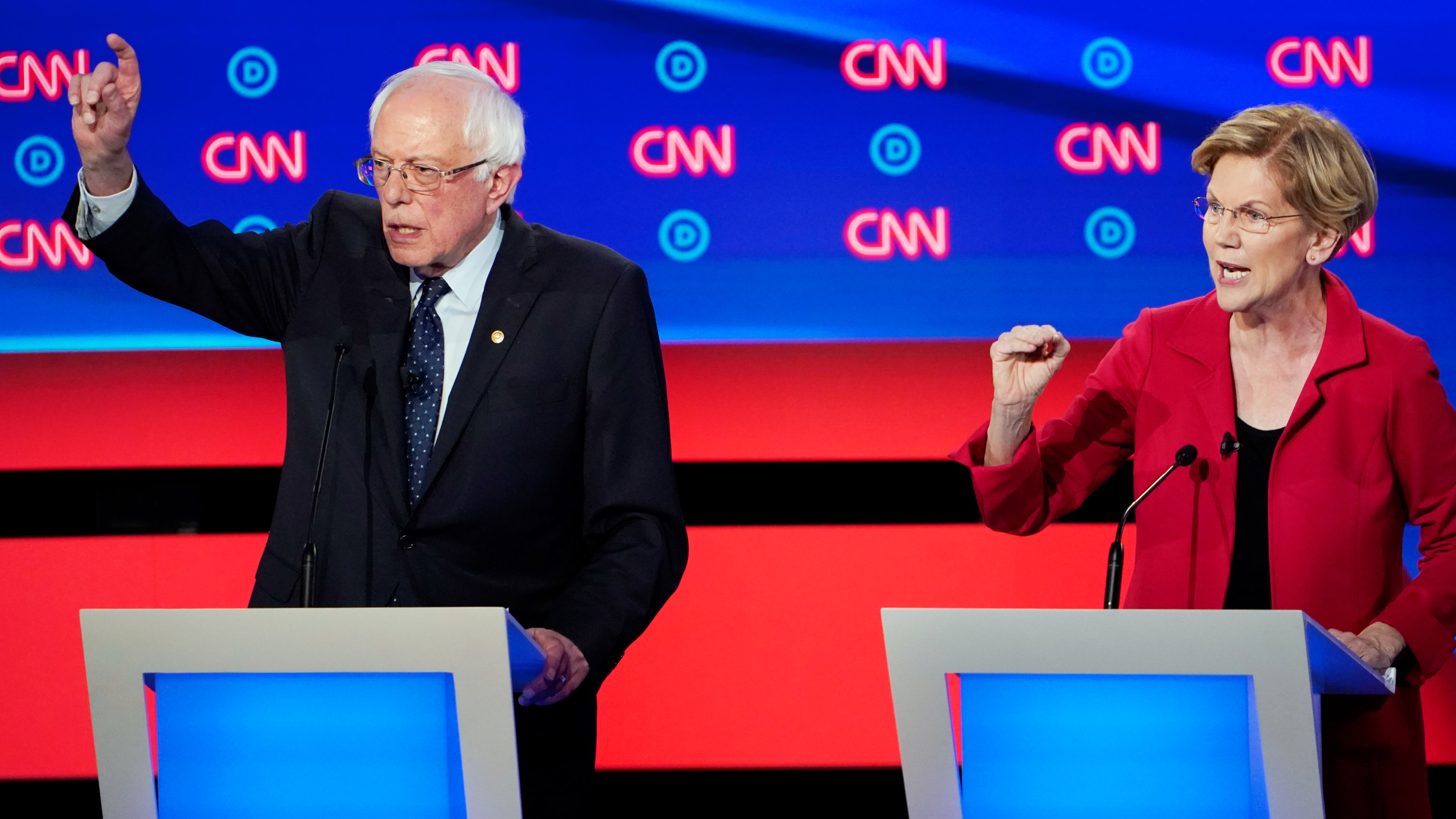

The leading progressives, Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, fended off attacks from underdog moderate challengers.CreditCreditErin Schaff/The New York Times

It is likely to repeat itself during Wednesday night’s debate, whose lineup includes former Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. and Senator Kamala Harris of California. He supports building on the Affordable Care Act by adding an option to buy into a public health plan. She released a proposal this week that would go further, eventually having everyone choose either Medicare or private plans that she said would be tightly regulated by the government.

Democrats know all too well that the issue of choice in health care is a potent one. When President Barack Obama’s promise that people who liked their health plans could keep them under the Affordable Care Act proved to be untrue, Republicans seized on the fallout so effectively that it then propelled them to majorities in both the House and Senate.

On Tuesday night, Representative Tim Ryan of Ohio evoked those Republican attacks of years ago on the Affordable Care Act, saying the Sanders plan “will tell the union members that give away wages in order to get good health care that they will lose their health care because Washington is going to come in and tell them they have a better plan.”

Republicans watching the debate may well have been smiling; the infighting about taking away people’s ability to choose their health care plan and spending too much on a pipe-dream plan played into some of President Trump’s favorite talking points. Mr. Trump is focusing on health proposals that do not involve coverage — lowering drug prices, for example — as his administration sides with the plaintiffs in a court case seeking to invalidate the entire Affordable Care Act, putting millions of people’s coverage at risk.

It was easy to imagine House Democrats who campaigned on health care, helping their party retake control of the chamber, being aghast at the fact that not a single candidate mentioned the case.

Mr. Sanders’s plan would eliminate private health care coverage and set up a universal government-run health system that would provide free coverage for everyone, financed by taxes, including on the middle class. John Delaney, the former congressman from Maryland, repeatedly took swings at the Sanders plan, suggesting that it was reckless and too radical for the majority of voters and could deliver a second term to Mr. Trump.

Mr. Sanders held firm, looking ready to boil over at time — “I wrote the damn bill,” he fumed after Mr. Ryan questioned whether benefits in his plan would prove as comprehensive as he was promising. Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, the only other candidate in favor of a complete overhaul of the health insurance system that would include getting rid of private coverage, chimed in to back him up.

At one point she seemed to almost plead. “We are not about trying to take away health care from anyone,” she interjected. “That’s what the Republicans are trying to do.”

[Bernie Sanders “wrote the damn bill.” Everyone else is just fighting about it.]

Mr. Delaney has been making a signature issue of his opposition to Medicare for all, instead holding up his own plan, which would automatically enroll every American under 65 in a new public health care plan or let them choose to receive a credit to buy private insurance instead. He repeatedly disparaged what he called “impossible promises.”

He was one of a number of candidates — including Beto O’Rourke, the former congressman from Texas; Senator Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota and Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Ind. — who sought to stake out a middle ground by portraying themselves as defenders of free choice with plans that would allow, but not force, people to join Medicare or a new government health plan, or public option. (Some candidates would require people to pay into those plans, while others would not.)

The debate moderators also pressed Mr. Sanders and Ms. Warren on whether the middle class would have to help pay for a Sanders-style plan, which would provide a generous set of benefits — beyond what Medicare covers — to every American without charging them premiums or deductibles. One of the revenue options Mr. Sanders has suggested is a 4 percent tax on the income of families earning more than $29,000.

In defending his plan, Mr. Sanders repeatedly pointed out how many Americans are uninsured or underinsured, unable to pay high deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs and thus unable to seek care.

Takeaways: The July 30 Democratic Debate

Here are the key moments from the Democratic presidential debate in Detroit.

Analysts often point out that the focus on raising taxes to pay for universal health care leaves out the fact that in exchange, personal health care costs would drop or disappear.

“A health reform plan might involve tax increases, but it’s important to quantify the savings in out-of-pocket health costs as well,” Larry Levitt, executive vice president for health policy at the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation, tweeted during the debate. “Political attacks don’t play by the same rules.”

A Kaiser poll released Tuesday found that two-thirds of the public supports a public option, though most Republicans oppose it. The poll also found about half the public supports a Medicare for all plan, down from 56 percent in April. The vast majority of respondents with employer coverage — which more than 150 million Americans have — rated it as excellent or good.

In truth, Mr. Delaney’s own universal health care plan could also face political obstacles, not least because it, too, would cost a lot. He has proposed paying for it by, among other steps, letting the government negotiate drug prices with pharmaceutical companies and requiring wealthy Americans to cover part of the cost of their health care.

Had Mr. Sanders not responded so forcefully to the attacks, it would have felt like piling on, though some who criticized his goals sounded more earnest than harsh.

“I think how we win an election is to bring everyone with us,” Ms. Klobuchar said, adding later in the debate that a public option would be “the easiest way to move forward quickly, and I want to get things done.”