LOS ANGELES — A few days after I visited Demi Moore in her home high above Beverly Hills, her daughter Tallulah Willis told me, “My mom was not raised, she was forged.”

But the woman who greeted me from atop a staircase, in the boxy residence she calls her “peaceful Zen treehouse,” and asked if I was chilly or needed a jacket, was not the steely star whose movies, like “St. Elmo’s Fire,” “Ghost” and “A Few Good Men,” helped define the 1980s and ’90s. She was not the stylized deity venerated on magazine covers, not the inadvertent pioneer for pay equity in her industry, nor the walled-off enigma who, by her own design, resisted most efforts to reveal the authentic person behind the adamantine roles she played.

Dressed in a long-sleeve T-shirt, moccasin boots and a pair of prescription glasses with transition lenses, Moore sat cross-legged on the floor of her living room that late August morning and told me the story of her life.

It is an exercise that she has already undertaken in a memoir, “Inside Out,” which Harper will release on Sept. 24. The book is a candid personal narrative, in which Moore fills in not only the details surrounding the most visible parts of her history — her Hollywood career and her much scrutinized marriages to the actors Bruce Willis and Ashton Kutcher — but the portions of her life that she once fought to protect, including the confusing and all-too-abrupt childhood that preceded her choppy show-business ascent, and a more recent relapse into substance abuse that nearly tore apart her family.

As she writes in a typically unsparing self-assessment, “if you carry a well of shame and unresolved trauma inside of you, no amount of money, no measure of success or celebrity, can fill it.”

With the publication of “Inside Out” approaching, Moore told me she was both eager and anxious, at the age of 56, to finally let audiences see her as she sees herself, without any barriers or artifices.

“It’s exciting, and yet I feel very vulnerable,” she said, twisting a finger through her long, dark hair. “There is no cover of a character. It’s not somebody else’s interpretation of me.”

If it is surprising to see such self-revelation from any prominent Hollywood actress — let alone one with Moore’s particular accomplishments and setbacks, and who admits to a reputation for reticence — she said that writing the memoir was a necessary part of a longer process of rediscovering herself. “I had to figure out why to do this, because my own success didn’t drive me,” she said.

And if the whole endeavor is construed as a bid for more movie roles or just to be back in the limelight, so be it. “It’s more of an awakening than a comeback,” she said.

‘I was just the instrument’

As Moore recounts in “Inside Out,” her upbringing was defined by constant motion, with stops in New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Washington State before her family landed in Southern California. Along the way her father, Danny Guynes, enlisted her to help him prevent her mother, Ginny, from following through on one of her frequent suicide attempts, and after they separated young Demi learned that Danny was not actually her biological father.

She writes about being raped at 15 and moving out of her mother’s home to live with a guitarist a day after her 16th birthday. Two years later, she married the rock musician Freddy Moore, a union that she says she quickly sabotaged with her infidelity.

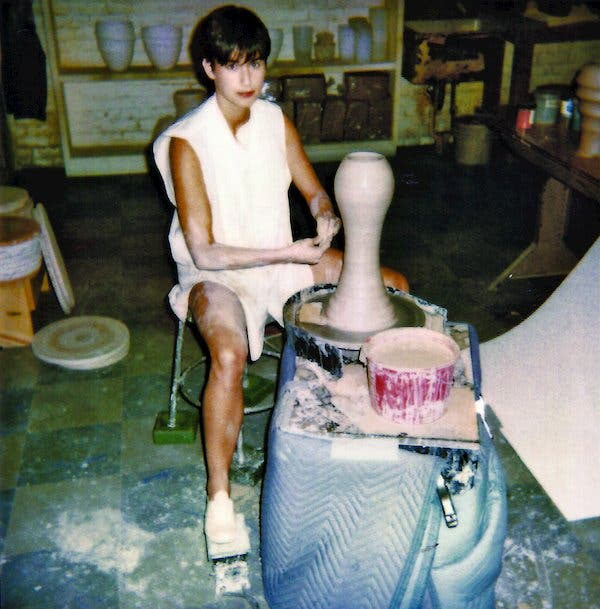

Her acting career, meanwhile, was exploding, as she parlayed a gig on “General Hospital” into lead roles in films like “Blame It on Rio” and “About Last Night…” If those earliest characters were often lust objects or required her to appear unclothed, Moore now says her jumbled feelings about desire and sexuality likely drew her to them. “When I was younger, I was obligated to be of service,” she told me. “I wouldn’t be loved if I wasn’t — if I didn’t give of myself. My value was tied into my body.” She abused alcohol and cocaine, binge-ate and obsessed over her weight.

Following a called-off wedding to Emilio Estevez, Moore married Willis, the taciturn action star, and they had three daughters, Rumer, Scout and Tallulah. Moore was starring in the most successful films of her career, including “Ghost” (which took in more than $217 million at the U.S. box office), “A Few Good Men” ($141 million) and “Indecent Proposal” ($106 million).

But just as quickly, the wheels came off: Moore writes that Willis was ambivalent about her work, which he felt took time away from their family, and he told her he was unsure if he wanted to be married. (A spokeswoman for Willis said he wasn’t available for comment.) When Moore started earning multimillion-dollar salaries, including a reported $12.5 million for “Striptease,” she was portrayed in the news media as greedy and given the derisive nickname “Gimme Moore.”

Today, Moore sees herself as the scapegoat of an entertainment industry that could not countenance its female stars being paid as much as its male leads (at a time when Willis was earning as much if not more for his films). To have been a trailblazer in this way, she said, “was an honor, and with that came a lot of negativity and a lot of judgment towards me, which I’m happy to have held if it made a difference.”

Does she think it did? I asked.

After a long pause she answered, “I do, actually. I know that it really resonated.” But, she added, “It’s not about me doing it. I was just the instrument by which it was done. Clearly it didn’t do enough because we’re still, this many years later, dealing with it.”

‘Women didn’t naturally fit into the system’

No setback deflated Moore quite like “G.I. Jane,” the Ridley Scott action movie for which Moore underwent weeks of training and a grueling shoot to play a fictional character attempting to become the first woman to complete Navy Seal training. That film was criticized by military veterans for inaccuracies and savaged by reviewers, ending up a box-office disappointment.

“They weren’t going to let me win,” she said. “That, to the little girl in me — that was crushing.”

Amid her divorce from Willis and her mother’s death from cancer, Moore stepped back from her acting work to focus on raising her daughters. Though she continued to produce films like the “Austin Powers” series, she acted only occasionally, in roles like the villain of “Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle.” She was in her early 40s and wondering if Hollywood had no more use for her.

“They’d say they don’t really know what to do with you, where to place you,” she said. “I was like, oh, well is that supposed to flatter me?”

Moore never spoke with bitterness when she discussed these experiences; if anything, she was soft-spoken and un-self-consciously goofy. At the start of our conversation she swigged on Starbucks and switched midway to alternating between sips of Red Bull and drags from a caffeine vape pen. She has surrounded herself in her home with small, affectionate dogs with names like Merple, Diego and Sousci Tunia, and she also collects taxidermy — like the baby zebra near her fireplace — of animals that she said “have had unfortunate early passings.” (She said she also had “a stillborn deer” in her home in Hailey, Idaho.)

To a slightly younger generation of film actresses, Moore is regarded as a both a tough-as-nails renegade and a nurturer. “She became a movie star in this time where women didn’t naturally fit into the system,” said Gwyneth Paltrow, who has become a friend of Moore’s. “She was really the first person who fought for pay equality and got it, and really suffered a backlash from it. We all certainly benefited from her.”

But before Moore could see her own self-worth she had to withstand another set of trials that eventually led to the creation of “Inside Out.” In 2003, she started dating Kutcher, disregarding the rubbernecking that their 15-year age gap invited and feeling, as she writes, that she was enjoying “a do-over, like I could just go back in time and experience what it was like to be young, with him — much more so than I’d ever been able to experience it when I was actually in my twenties.”

She became pregnant soon after, with a girl who she intended to name Chaplin Ray, but Moore lost the child about six months into the pregnancy. She had started drinking again and blamed herself for the loss. Moore and Kutcher married in 2005 and pursued fertility treatments in hopes of getting pregnant again. But her drinking worsened, and she started abusing Vicodin, all before learning that Kutcher had cheated on her. (They separated in 2011 and divorced two years later; his spokeswoman didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

Things somehow got worse still. While partying with Rumer in 2012, Moore suffered a seizure after smoking synthetic cannabis and inhaling nitrous oxide. Her hedonistic behavior had already alienated Scout and Tallulah, and now all three of her daughters were shunning her.

At the time, Moore had signed with Harper to write a memoir, one that she intended to be about the mothers and daughters in her family. But those plans would have to wait: “Part of my life was clearly unraveling,” she told me.

“I had no career,” she said. “No relationship.” And then her health began to deteriorate, as even basic tasks like reading and watching TV became incapacitating. Moore was experiencing autoimmune and digestive problems and, while she was circumspect about telling me the exact diagnosis she received, she said, “Something was going on, including my organs slowly shutting down,” adding that “the root was a major heavy viral load.”

Recovery, reconciliation, ‘it’s all been in alignment’

Little by little, Moore pieced things back together. She went to a rehab program for trauma, codependency and substance abuse and worked with a doctor specializing in integrative medicine to rectify her health problems. Gradually she began to reconcile with her daughters and, about two years ago, got serious about the writing of “Inside Out,” which she accomplished with a co-author, Ariel Levy, a staff writer for The New Yorker and a memoirist as well.

At the outset of their collaboration, Levy said she encouraged Moore not to censor herself, but found that she did not need much reassurance in this area. “Let’s just get it out,” Levy said she told Moore, “and in the end, anything that you’re like, ‘That’s actually too private,’ we’ll take it out. And that step kind of never happened.”

Paltrow, in particular, credited the memoir with helping to reduce Moore’s health problems by unburdening her of the psychic baggage she’d been carrying. As women, Paltrow said, “We think we just have to get through everything and bear the burden for everyone in our family.”

Moore’s book, she said, went hand-in-hand with “her healing journey — physically, mentally, emotionally. It’s no accident that it’s all been in alignment and all happened at the same time.”

Moore said she had little concern that anything she wrote would cost her any standing in her industry. “There’s nothing I have to protect,” she said. “Really.”

She also felt strongly that she had the right to share stories that involved her famous ex-husbands if these episodes were principally about her, and she was confident that her portrayals of them did not make them into villains or her into a victim.

“I’m definitely not interested in blaming anyone,” Moore said. “It’s a waste of energy.”

She thought further on this. She started to say, “I hope that everyone that’s in the book feels like it’s — ” She paused, then added, “I don’t know what I hope they feel.” With a chuckle, she said, “Good, not bad.”

‘Soul-centered living,’ and working

For Moore’s daughters, “Inside Out” is a more fraught project. Each said they were given the opportunity to review a copy of the manuscript and ask for changes, though none of them requested revisions.

Scout Willis told me she was proud of her mother for “doing the internal work that she didn’t have the time to do, for a long time, because she was just in survival mode.” Writing the memoir, Scout said, “really denotes a certain amount of safety and comfort with herself.”

At the same time, she said the book resurfaced uncomfortable memories for her and her sisters, who have dealt with substance abuse and body-image issues of their own.

“It’s challenging because she’s making this amazing effort to put out the most vulnerable moments of her life,” Scout said. “It just happens that it also coincides with some of the most challenging and traumatic times of mine.”

Rumer Willis said the book was an opportunity to learn her mother’s history, some of which Moore had hinted at over the years but never told them in this much detail.

“We grow up thinking that our parents are these immovable gods of Olympus,” Rumer said. “Obviously, as we grow older, we start to realize how much our parents are just people.”

Moore said she has maintained her sobriety and that she, Rumer and Scout are seven months into a 10-month course on spiritual psychology, which she said teaches “soul-centered living.” (Moore is no longer involved with kabbalah studies — “not the human organization, which is human, so it’s imperfect,” though she said its teachings provided her with “a lot of wisdom that I still really value.”)

She continues to act in ensemble roles that she hopes will take her outside her comfort zones: She is among the cast members of a USA Network adaptation of “Brave New World” and plays an obnoxious executive in the dark comedy “Corporate Animals,” a part originally intended for Sharon Stone. And she is still developing material for herself, mentioning that a project about Isabella Goodwin, the first female police detective in New York City, could provide “a pretty spectacular character.”

Moore’s already been asked if she wrote “Inside Out” for the money, and before I could ask her again, she answered herself: “Uh, definitely not,” she said with a knowing laugh. “Because there’s a lot of easier ways to do that.”

But the idea that “Inside Out” might be perceived as a work of image management — an effort on Moore’s part to replace the version of herself that people perceive with the one she wants to be seen as, or provide one where none currently exists — is one that she wholeheartedly embraced. “I would say, yeah,” she replied. “Great! Why not?”

“Did you know me before?” she asked, already expecting that I would answer no. “Well, there you go,” she said. “That’s what I would say.”

Follow New York Times Books on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, sign up for our newsletter or our literary calendar. And listen to us on the Book Review podcast.