The scene played out for years. Twice a week, in the late afternoon, above the Shun Lee Chinese restaurant on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, a creaky elevator would open, and out would step an elderly man. Thin as a rail, with a sparse mustache, he would sometimes have little idea about where or who he was. A pair of security doors would buzz unlocked once surveillance cameras identified him as the artist Peter Max.

Inside, he would see painters — some of them recruited off the street and paid minimum wage — churning out art in the Max aesthetic: cheery, polychrome, wide-brushstroke kaleidoscopes on canvas. Mr. Max would be instructed to hold out his hand, and for hours, he would sign the art as if it were his own, grasping a brush and scrawling Max. The arrangement, which continued until earlier this year, was described to The New York Times by seven people who witnessed it.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Mr. Max was a countercultural icon, a rare painter to achieve name recognition in the mainstream. His psychedelic renderings could be found on the cover of Time, the White House lawn and even a postage stamp. But several years ago, he received a diagnosis of symptoms related to Alzheimer’s, and he now suffers from advanced dementia. Mr. Max, 81, hasn’t painted seriously in four years, according to nine people with direct knowledge of his condition. He doesn’t know what year it is, and he spends most afternoons curled up in a red velvet lounger in his apartment, looking out at the Hudson River.

For some people, Mr. Max’s decline spelled opportunity. His estranged son, Adam, and three business associates took over Mr. Max’s studio, drastically increasing production for a never-ending series of art auctions on cruise ships, even as the artist himself could hardly paint.

Then, in 2015, Mr. Max’s second wife, Mary, asked a New York court to appoint a guardian to oversee her husband’s business. Soon after her request was granted, Adam took his father out of his home for more than a month, moving him between various locations around New York.

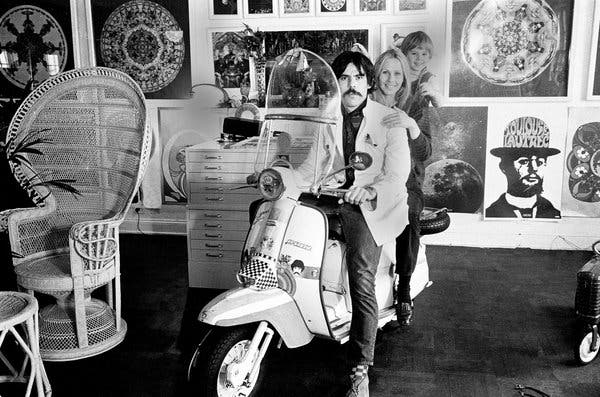

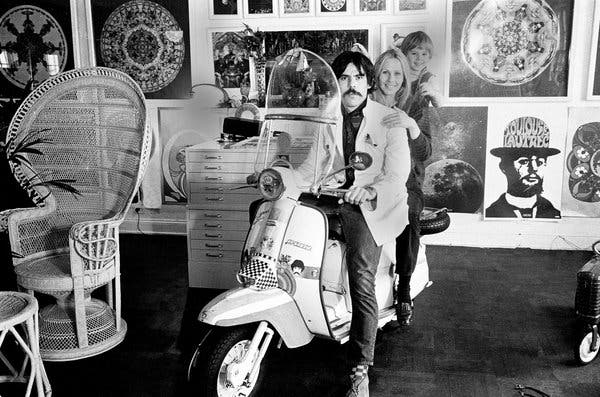

Mr. Max and family in 1967.CreditSanti Visalli/Getty Images

For five years and counting — the latest lawsuit came Friday — the artist’s family, friends and associates have been trading lurid courtroom allegations of kidnapping, hired goons, attempted murder by Brazil nut, and schemes to wring even more money out of what was already one of the most profitable art franchises in modern times. From Shun Lee to the high seas, the twilight years of Mr. Max’s life have produced a pursuit of art-auction profits and a trail of misfortune as surreal as his trippiest works.

‘Portrait of the Artist as a Very Rich Man’

Peter Max Finkelstein was never very discerning about his art. He was the son of German Jews who fled Berlin in 1938 and settled in Shanghai, where Mr. Max discovered the primary hues he’d been deprived of under bleak Nazi rule. Eventually, the Finkelsteins moved to Brooklyn, and by 1968 their son was a bona fide Pop Art sensation. But while other protagonists of the movement — like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein — used their art as a commentary on commercialism, Mr. Max’s happy palette defined it.

His DayGlo-inflected posters became wallpaper for the turn on, tune in, drop out generation. And as the hippies who loved his work grew up and became capitalists, so did Mr. Max. He painted a Statue of Liberty series with the backing of Lee Iacocca, the celebrity chief executive of Chrysler. He painted official artwork for the Super Bowl, the United States Open tennis tournament and the World Cup. He splashed his art on cereal boxes, bedsheets, a chunk of the Berlin Wall and Dale Earnhardt’s racecar. When Mr. Max appeared on the cover of Life, it was under the headline “Portrait of the Artist as a Very Rich Man.”

Money let Mr. Max indulge his eccentricities. After he divorced his first wife, Elizabeth Nance, in 1976, a staircase in his duplex connected two apartments so that she and their two children, Adam Cosmo and Libra Astro, could live downstairs. Mr. Max went on to have dalliances with Rosie Vela, a model, and Tina Louise, who played Ginger on “Gilligan’s Island.” In 1996, on a Manhattan sidewalk, Mr. Max spotted Mary Baldwin, a blond pixie with a Mia Farrow haircut, some 30 years his junior. He walked up and said, “Hi, I’m Peter Max, and I’ve been painting your profile my entire life.” They married a year later, officiated by Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani.

By then, critics were dismissing Mr. Max as more artsy than artist, more concerned with commercial viability than creating museum-grade masterpieces. Mr. Max had a knack for the squishy business of art; he used to joke that “the difference between a $10,000 painting and a $20,000 painting is a couple inches of canvas,” according to a business associate who heard Mr. Max say this. In 1997, his looseness with money went too far, and he pleaded guilty to hiding $1.1 million in income from the I.R.S. Struggling financially, Mr. Max expanded a partnership with an organization called Park West Gallery.

Before founding the gallery in 1969, Albert Scaglione taught mechanical engineering at Wayne State University. Today he boasts that Park West is the world’s largest private art gallery, one that has sold 10 million works for billions of dollars. The majority of its revenue comes from boozy auctions held on cruise ships — and on the water, nobody sells like Mr. Max. One participant in a 2003 sales training session recalled Mr. Scaglione handing out two books: the Bible and “The Art of Peter Max.” (Through a lawyer, Mr. Scaglione said this did not happen.)

For the high-end clientele of Sotheby’s and Christie’s, Peter Max hardly registers. But for the 24 million people who take a cruise each year, Mr. Max is a star. This is an alternate, at-sea universe in which his works are the pinnacle of sophisticated collecting. Maxes can be found in Park West showrooms on all of the major cruise lines, including Royal Caribbean, Carnival and Norwegian. They promote the Park West auctions as an exhilarating onboard activity with complimentary Champagne — and take a cut of as much as 40 percent of sales, according to industry analysts. Norwegian has an entire Peter Max-themed ship, whose hull is dominated by his sunny Statue of Liberty and New York skyline.

With vacationing baby boomers bidding up his work, Mr. Max maintained his Manhattan lifestyle into the 2000s. He would attend galas with Ms. Max, then paint at his studio until 4 a.m., blaring Rage Against the Machine and Led Zeppelin. Ringo Starr and Herbie Hancock would stop by, enjoying takeout from Shun Lee.

Mr. Max was so prolific — and Park West was such a voracious buyer — that like many popular artists, he often relied on assistant painters to stretch canvases, paint backgrounds and apply templates. But Mr. Max always did the creating, according to individuals familiar with his work in this period. “These people would come in with boards and they’d be one-tenth done, the backgrounds, and Peter would do the images,” said Leo Bevilacqua, a photographer and close friend.

Mr. Max’s best pieces, however, were often not going to Park West’s auctions. One version of his creations — called “Peter’s keepers” — went to a warehouse in Lyndhurst, N.J. Lesser derivatives were touted on the cruise ships, where they would sell for as much as $30,000. Over the years, dissatisfied Park West customers complained that they were led to believe they were buying “one of a kind” Max works that would appreciate in value, only to return to land (and reliable Wi-Fi) and learn that the internet was glutted with similar works. There were more objections to works by other artists, including Salvador Dalí.

More than a dozen people sued; Park West either settled the cases, or they were dismissed. (Lawyers for the company said that the works in Mr. Max’s warehouse are not duplicates, and that every Max the gallery sells is unique. They also said that Park West instructs auctioneers to never use the word “investment” when describing art.)

‘He doesn’t do a blink of art’

By 2012, Mr. Max’s mental faculties were beginning to wane. He would sign books, squiggle designs on cocktail napkins for dinner companions, or hold a brush and put some paint on canvas for public appearances, but he struggled to truly create. In the next couple of years, Mr. Max stopped painting almost entirely. “The cruise ship art, he signs his name but he doesn’t do a blink of art on there,” Mr. Bevilacqua said. “He’s not capable of doing it anymore.”

Mr. Max’s studio is organized legally as ALP Inc., named after its three principals: His children Adam and Libra each own 40 percent, and Peter owns the remainder. As Mr. Max became increasingly unable to produce, ALP defaulted in 2012 on $5.4 million in bank loans, according to recent court filings.

Mr. Max asked Lawrence Moskowitz, an insurance agent, and Robert M. Frank, an accountant in Amityville, N.Y., to help revive the business, according to a lawyer for Mr. Moskowitz. After Hurricane Sandy struck in the fall of 2012, he and Mr. Frank assisted in claiming $300 million in flood insurance on the New Jersey warehouse where ALP stored “Peter’s keepers.” So far, they’ve recouped $48 million, with Mr. Moskowitz taking a 10 percent fee.

Mr. Moskowitz took a more active role in running the drifting studio. In exchange, his lawyer said, Mr. Max offered him 10 percent of ALP — half the artist’s stake. Mr. Moskowitz established an alliance with Gene Luntz, Mr. Max’s longtime salesman on his Park West account, and encouraged Adam Max to get more involved in the business.

Although Adam had technically been the president of ALP since its inception, in 2000, he had shown little interest in the day-to-day of his father’s business. But with his sister, Libra, living in Los Angeles, volunteering as a prominent animal rights activist, Adam began to work with Mr. Moskowitz to turbocharge ALP. He would later tell a court that his father asked him to take over active management.

Adam Max, Mr. Moskowitz and Mr. Luntz drastically increased business with Park West, relying on an expanding cast of artists to mimic Mr. Max’s more commercial work. In the acrylic-spattered space above the Chinese restaurant, according to seven people who have seen it, there were as many as 18 assistant painters and five people working on etchings.

To secure the studio, Adam Max installed surveillance cameras and doors with metal bars. His lawyer, Michael C. Barrows, said Adam deemed the measures necessary after noticing stolen works listed for sale online. He also began to monitor his father’s phone conversations and movements, according to court filings and people who observed the behavior. Mary and Libra Max, who had started to become increasingly concerned about her father, would later allege in separate court proceedings that they were both barred from the studio.

Peter Max continued to keep up appearances. His hip fashions, dyed brown hair and slim physique made him look physically healthy, even as his mental capacity diminished. Park West would request his presence at V.I.P. sales events, sometimes asking him to visit several cities in a weekend, according to three people who accompanied him. The gallery can sell more than $2 million worth of art on a single big-spender cruise, and meeting Peter Max in person was the ultimate perk.

Mr. Max played the part, but he was often confused and exhausted, according to the travel companions. He soiled himself on one cruise, said one person who was with him at the time. Back in New York, Mr. Luntz would take his usual 15 percent agent’s commission of what Mr. Max made on the road. Privately, Mr. Luntz called Mr. Max “Bozo,” as in the clown, according to a Max family friend. (Mr. Luntz declined to comment.)

The lawsuits begin

Some Max collectors started to hear that Mr. Max wasn’t painting. In a 2014 lawsuit against the artist, two New York businessmen, who had helped sell a rendition of Mr. Max’s Statue of Liberty series to a collector for $500,000, said they overheard Mr. Moskowitz remark that the artist had “not painted in years.” The suit alleged that a team of “ghost painters” created his pieces, and that “the extent of Mr. Max’s involvement with these paintings is limited to merely signing his name on the artwork when it’s completed.”

The case is continuing. A lawyer for Mr. Moskowitz disputed that his client made those statements. He added that Mr. Moskowitz had observed Mr. Max putting paint on canvas in recent years, but couldn’t say whether he had produced complete works.

The next year, 2015, is when Mary Max asked the Supreme Court of the State of New York to appoint a guardian to oversee her husband’s business. She later told the court that she began to be followed by private investigators and threatened by men who approached her on the street, warning her to stop interfering in her husband’s business.

The accusations only got more sensational. Ms. Max told the court that Adam had taken custody of his father and concealed his whereabouts from friends and family — that he had effectively “kidnapped” Mr. Max, according to court filings.

Adam said he was protecting his father from his stepmother’s verbal and physical abuse. Several sworn affidavits described Ms. Max as a neglectful, even punishing, figure in her husband’s life — a view that even came to be supported by the guardian she had sought to appoint.

In a transcript of a recorded conversation with her driver entered into evidence, Ms. Max inquires about hiring a goon to intimidate her husband and damage his painting hand. Several household employees also made allegations of neglect, including that Ms. Max withheld food from her husband and sometimes put “large Brazil nuts” in his smoothies, on which he might choke.

A lawyer for Ms. Max, John Markham, said that she and Mr. Max “adore each other, and she is very devoted to him.”

Not everyone agreed with the portrayal of an abusive marriage. One court-appointed lawyer testified that Mr. Max “stated several times, without prompting, how much he loved his wife” and that removing him from their home could be “highly detrimental” to Mr. Max’s mental well-being. Ultimately, a judge ordered Mr. Max to be returned to his wife’s care at their Riverside Drive home, appointing a guardian to oversee both his business and personal matters. Mr. Max continued to travel to the studio above Shun Lee and sign works of art, even as his condition steadily worsened.

As the Max family drama has played out, sales at Park West’s seaborne auctions have continued to infuse the studio with cash. According to an audit included in recent legal proceedings, from 2012 to 2018 ALP went from insolvency to Mr. Luntz generating a total of more than $93 million in sales. Its net profit for 2018 was more than $30 million — the studio’s best year ever.

Mr. Luntz’s lawyer, Gregory A. Clarick, said everything his client did was authorized by Mr. Max and, later, Adam Max. He added that Mr. Luntz “had no reason to believe at any time that any artwork ALP was selling was anything other than original and authentic Peter Max work.” (Mr. Frank, the accountant, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

Arguing that dementia fuels creativity

Park West is still aggressively selling Peter Max aboard the world’s cruise ships. Just before Christmas, the gallery had some of the best real estate on the Mariner of the Seas, a Royal Caribbean ship drifting through the mint-blue waters off Coco Cay in the Bahamas. With Max pieces front and center, Park West had set up in a narrow corridor between the main dining room and the restrooms, which made it hard for anyone who went to dinner and had to use the toilet to avoid a Park West salesperson.

Before an auction one afternoon, I asked a Park West employee named Steven — a South African in a sharp black suit — about the prominently displayed Maxes. He called Mr. Max “America’s painter laureate” and started in on a sales pitch for “Umbrella Man,” a florid silhouette of the back of a bulbous man in the rain. It was valued, he said, at $30,000.

Steven then turned to a framed rendering of an American flag, which he said Mr. Max painted in 2016. The artist’s dementia, Steven continued, made Mr. Max even more creative and prolific. He offered me a mimosa and a line of credit with a V.I.P. Park West monthly payment plan. (A lawyer for Park West said employees were instructed not to say Mr. Max’s dementia has made him more prolific.)

Soon there was a standing-room-only crowd. “Time and again our V.I.P. collectors come in on cruises with one purpose and one purpose only,” Steven told the group. “To collect a Max.” A man in the front row was wearing a blue muscle shirt and backward cap, his drink pass hanging around his sunburned neck. When he heard Mr. Max’s name, he shouted, “That’s why I’m here!”

This pleased Steven. “If you want to walk off this ship with a superb artist, if you want to take your art to the top level of collecting, look no further,” Steven said. He added, “The fact that you can collect a Peter Max for way under $250,000 is astonishing.”

An encounter with Mr. Max

Libra Max, distressed about her father’s declining health, started to get more involved in the family business about two years ago. In January 2019, she and Mr. Max’s guardian voted to oust Adam from ALP and name her president and chief executive. Weeks later, she filed a lawsuit to restrain Adam from interacting with the company. She also terminated Mr. Moskowitz and Mr. Frank’s consulting agreements, and fired many of the studio’s assistant painters.

In a statement, Libra said that she was pursuing legal action “against those who continue to harm and exploit my father” and that her goal “is to bring the studio back to my father’s vision.”

In part, that means keeping Mr. Max’s art accessible, but pulling back from the kitschy renderings of Marilyn Monroe popular with Park West’s clientele and showcasing his earlier, edgier work in coastal galleries and museums.

She has also entered open warfare against Park West. In April, Libra filed a lawsuit alleging the gallery improperly took some 23,000 works from Mr. Max’s trove of “keepers,” paying approximately $14.7 million when their actual value was at least $100 million.

The day before, Park West, after learning that Libra had concerns about the deal, sued ALP, alleging breach of contract. (ALP has moved to dismiss the complaint.) Park West says the allegations in Libra’s suit are baseless.

Luke Nikas, a top art lawyer in New York, said Park West first heard last fall that Mr. Max wasn’t painting, when Mr. Nikas and others — including The New York Times — received an anonymous tip. Park West hired Mr. Nikas and Robert Wittman, a former F.B.I. agent who specializes in art fraud, to conduct an investigation. The inquiry concluded that the studio “met every legal standard you can come up with,” Mr. Nikas said. He did not dispute that Mr. Max suffered from dementia, and noted that the 20th-century Dutch-American artist Willem de Kooning also had the ailment and remained productive.

He compared Mr. Max to Warhol and conceptual artists like Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst, who exert creative control but typically rely on others to paint or construct the art. “Not a single work goes out the door without being hand signed by Peter Max,” Mr. Nikas said.

In a stratified art market, he added, “when there is so much criticism of wealth and money,” Mr. Max’s process allows “ordinary people the opportunity to buy something that is authentic.”

Paul J. Schwiep, a lawyer for Park West, said that he and Mr. Scaglione, the company founder, visited the studio in February and saw Mr. Max painting — an anecdote that also appeared in Park West’s legal complaint against ALP. “He complained about how much he was working, said he’s never been busier in his life,” Mr. Schwiep said. Mr. Nikas later told me that Mr. Schwiep misspoke, and that Mr. Max had only been signing prints the day Mr. Scaglione visited, not painting.

One Wednesday evening in April, I showed up at Peter Max’s apartment. A housekeeper instructed me to take off my shoes and wipe the bottom of my bare feet with disinfecting wipes. The blinds were pulled, and Mr. Max was alone at a marble dining table eating vegetarian sushi and drinking what looked like chocolate-flavored Ensure. There were minimal furnishings except for a piano covered in a plastic tarp and a couple of yoga mats. The air smelled like a mix of patchouli and Clorox.

A coffee-colored cat, one of at least a half dozen, curled up in Mr. Max’s lap. I spotted the winding staircase he’d used after his divorce. I told Mr. Max that I was a Times reporter — and that two family friends had suggested that I stop by — but he didn’t seem to understand. He just shrugged, asked me several times what year it was and then told me that he had spent his childhood in Shanghai.

For months, I’d been hoping to speak with Mr. Max. I wanted to ask him directly about his career and the drama of recent years, but now that I saw his confusion for myself, I didn’t attempt an interview. So I thanked him and turned to leave.

That’s when I spotted one of his earlier works hanging on an otherwise empty wall. The deep movement of the piece drew me in — the teals and yellows of an otherworldly garden party bouncing from the canvas and radiating something joyful. It hit me that long before a Max work ever sold on a cruise ship, the man had been a great — even avant-garde — artist.

The painting stayed with me, and as I walked back out onto the street, I thought about an old Max comment I had recently seen on the Park West website. “I’m just wowed by the universe,” Mr. Max had said. “I love color. I love painting. I love shapes. I love composition. I love the people around me. I’m adoring it all. My legacy is in the hands of other people.”