“Some people have hives for entertainers. I have hives for food,” Damon Young, the editor in chief of the pop culture criticism website Very Smart Brothas, said during a recent interview. He listed the hives he belongs to: Bacon hive. Pancake hive. Brussels sprouts hive. Crab cake hive. This sort of associative humor is typical of Young’s pieces on Very Smart Brothas, where he has been writing listicles, explainers and blog posts since 2008, when he founded the site with two other writers. (One of them, Panama Jackson, still serves as its senior editor.)

At first, Very Smart Brothas was a means to an end: the prospect of a cushy job as a writer at a more established publication. But as the site grew in popularity, those same publications — like GQ, Ebony and New York magazine — started asking him to contribute, and Young wondered whether “instead of using V.S.B. as a means to an end, I could just bring it all to me,” he said.

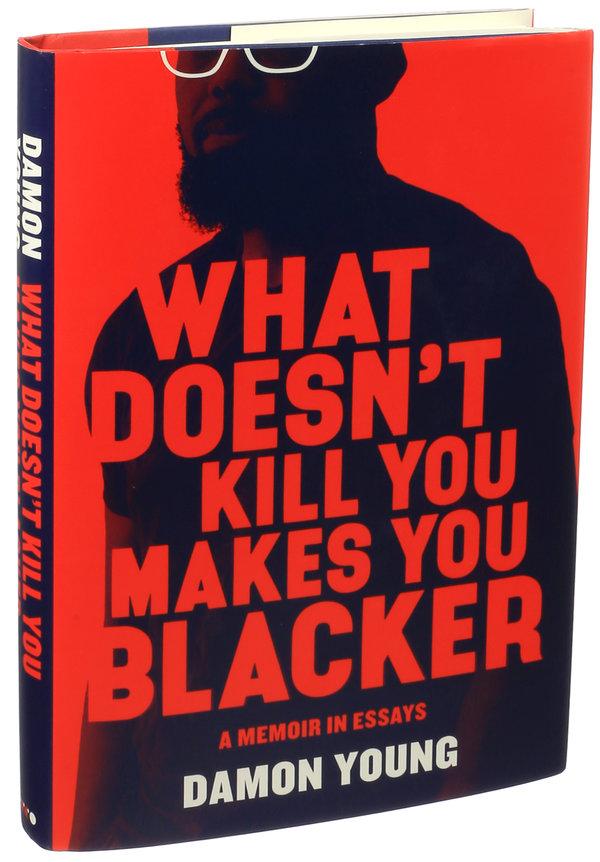

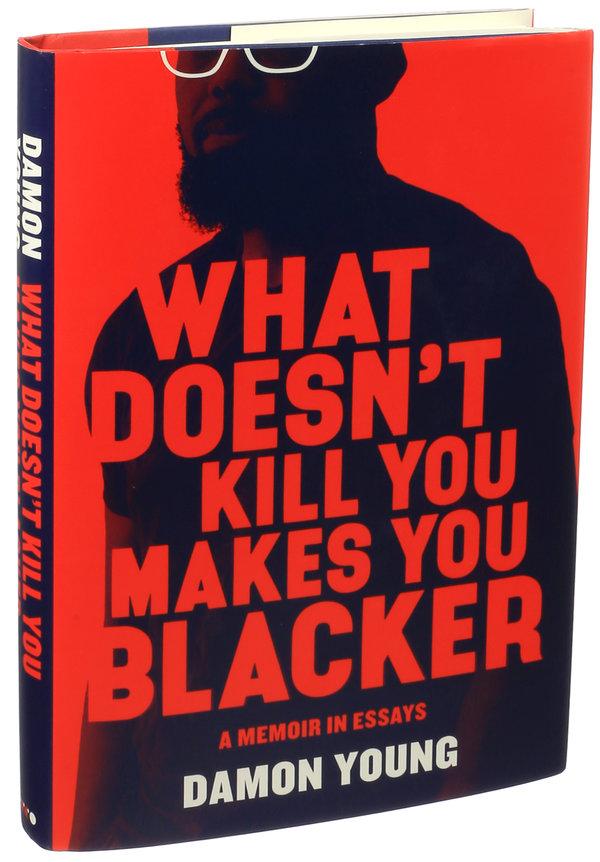

Young decided to stay in Pittsburgh, his hometown, and in 2017, Very Smart Brothas was acquired by Univision and merged with The Root, another black news and culture site. (Univision announced last year that it was selling the site.) Young wouldn’t discuss the particulars of the deal except to say that he makes “upcharge money” now, meaning that he can add protein to any salad he orders “and not have to think about it.” He’s also made enough to buy a house in Pittsburgh, where he lives with his wife, Alecia, and their two children. Now, he has written a book, “What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Blacker: A Memoir in Essays,” out March 26 from Ecco, about growing up in “the Burgh,” reckoning with his masculinity and navigating economic insecurity through his 20s and early 30s.

Ahead of the memoir’s release and a 14-city book tour, Young discussed why Pittsburgh is a character in his book, the challenges of writing a memoir and more.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

CreditPatricia Wall/The New York Times

Why does Pittsburgh loom so large in the book?

I don’t have that many supporting characters in my book, so I felt I needed to make Pittsburgh one of them. I love watching “Desus and Mero,” and many of their jokes are so insular and New York specific, but they work because, even if you don’t know the reference, you recognize their rhythms, the intent and the communal connection with the humor. So I was like: Why not do it with Pittsburgh? I will make these Pittsburgh references; I will make this a very Pittsburgh book. And even if people haven’t been or don’t know the differences between East Liberty and Homewood or the David’s Shoes theme song — which I have memorized — or don’t know what Pittsburgh, young, black, and successful means, they will be able to recognize a similar dynamic in their city. I didn’t want to scrub Pittsburgh from this because Pittsburgh is me.

Why have you stayed?

I guess the most prominent reason is that Pittsburgh is very cheap, so I was able to make a career as a freelancer, as a person who was running V. S.B., and not have a day job for a while. I was on unemployment for a couple of years after I got laid off at Duquesne University in 2009. I ended up getting a job with Ebony, but even then, I was making $3,000 a month at most. In Pittsburgh, that was enough to pay my rent, pay my car payments and go to brunch once a month. Now, particularly with the things that have happened within the last three or four years, there just isn’t as much incentive to leave.

“So much of the national dialogue about race deals with either terrible trauma or black excellence,” Young said. “I was more interested in the space in between, because that’s where I exist.”CreditKristian Thacker for The New York Times

When you started writing this book, was there a sense that you had already poured everything into the website? Were you worried you had run out of things to say?

Well, with V.S.B., the majority of the pieces are reacting to things happening in the news. The book is much more personal, much more vulnerable. In the introduction, I have an entire paragraph about masturbation. There is also the thread of economic insecurity throughout my life. There are entire chapters about the levels of self-consciousness I possessed about my masculinity and my blackness, and how they impacted decisions that I have made. There is a chapter about how my wife and I got together. I think people who know me from V.S.B. and read this book might be anticipating a different sort of book.

How did you recall these specific references? Did you keep journals growing up?

I did not keep journals. My dad has been a reliable archivist. Or as reliable an archivist as a person can be. So many of the stories in the book, my dad tells like once a year — at family reunions, at picnics. So it’s not like I had to remember this thing that happened in 1985. I was reminded of it in 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005.

What were some of the challenges of writing this?

I didn’t want to encapsulate my existence as very traumatic and downtrodden, like “Great Expectations.” So much of the national dialogue about race deals with either terrible trauma or black excellence. I was more interested in the space in between, because that’s where I exist. So the challenge was finding a space between sensationalizing and also documenting and contextualizing.

In writing a memoir you are forced to reinterrogate beliefs and feelings that may have settled over decades, and you start to realize that maybe in this story where I was the victim I was actually the villain. Maybe this person who I considered to be so confident was actually performing just like I was. Maybe I didn’t treat that girlfriend as well as I thought I treated her.

You write a lot about how your relationships with women have evolved over the years, sometimes in less than flattering ways. How did you approach that topic?

I wrote a memoir. This wasn’t “Black Panther.” This wasn’t a superhero origin story. In order to write a compelling memoir, I had to tell the truth. And the truth is unflattering. The truth is embarrassing. But that truth is also human. So whenever I have those critiques about toxic masculinity, I am not absolving myself. I am not saying, you guys need to do better, it’s “we.” Even if I have had whatever incremental revolution necessary to make those statements, I have still been socialized. I don’t want to position myself as some sort of singular beacon of progress, because I’m not that at all. I am still definitely a work in progress. I just don’t want to hurt people.

You approach heavy topics — death, financial insecurity, racism — with humor. Why?

It is essential. I feel like stories that neglect humor are incomplete because there is so much space for it. It is a very human reaction, even to trauma. Sometimes things could be so absurd and surreal that you have to laugh. It’s a good catharsis.

Masculinity, and in particular black masculinity, is also a theme. What were you trying to convey about the black male experience (or, rather, your experience as a black man)?

I cultivated a lifetime’s worth of Oscar-worthy performances attempting to meet a certain hyper-heterosexual ideal I believed — and still kind of, sort of believe — was/is expected of me. The economy of performance exists throughout the book. Here’s me on a date at 24 pretending that my driver’s license was suspended because, one, admitting that I didn’t have one would have dented that hyper-hetero facade and two, saying it was “suspended” also added a level of badassness.

Or when I was like 14, 15 years old, and I actually wanted to be called the N-word just so I could have a fight story. And when that doesn’t happen it’s like, What is it about me that doesn’t make you think that I am a threat? Just admitting that out loud and knowing that people are going to read that, it’s absurd. Obviously it’s this terrible, horrible thing, being called the N-word. But it’s connected to the absurdity of trying to make sense of existing while black, coping with it. You get to a point where you are anticipating bias.

The book attempts to articulate how essential and inextricable performance is to masculinity, and how surreal — and sometimes dangerous, for us and for the people we encounter — that can be.

You are also very open about how much money you were making in your 20s. Why was it important to include that? And could you talk about the transition from financial insecurity to financial stability?

The tenuousness of money has dictated my decisions, actions, thoughts, ideas, plans and dreams. It is much easier to talk about those experiences now. Back then I didn’t write about it because I was embarrassed. Collectively, as a culture, we assign so much of our self-worth to our net worth. I wanted to let people who are going through similar circumstances know that they are not alone. That there are other people who have that same sort of economic anxiety, and experience some of the same triggers and fears. And while my financial circumstances have (drastically) changed, that latent tenuousness is still there. I still feel as if it can disappear this week. Tomorrow. Today. And that’s because it can.

What advice do you have for aspiring writers who come from a similar background?

Move to Pittsburgh. We need you. It’s a city where you can survive as a working artist. Or marry someone who is rich.