MALI STON, Croatia — “An oyster leads a dreadful but exciting life,” M.F.K. Fisher observed in her classic book about them, “full of stress, passion and danger.”

The oyster, in other words, fits right in with the beleaguered Balkans.

In his 62 years in this tumultuous region, the life of Bode Sare has been at least as eventful as an oyster’s. Mr. Sare has been a partisan warrior, a weapons smuggler, a cafe owner and a prisoner (twice).

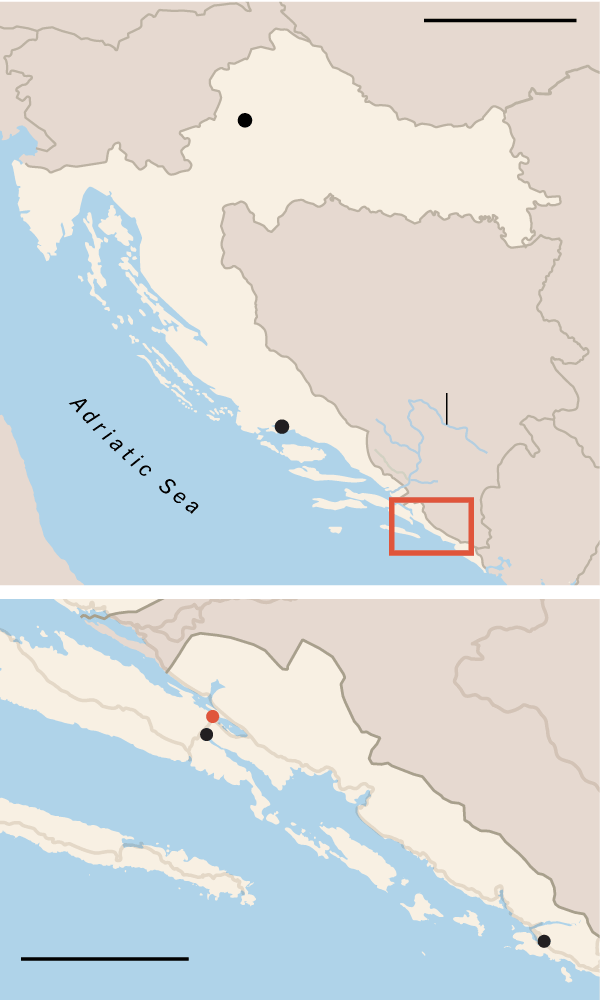

Now, as the owner of highly regarded seafood restaurants in Croatia, he champions locally grown oysters, and is part of a collective of 75 farmers that tends oyster beds in Mali Ston Bay, part of the Adriatic Sea along the southern Croatian coast.

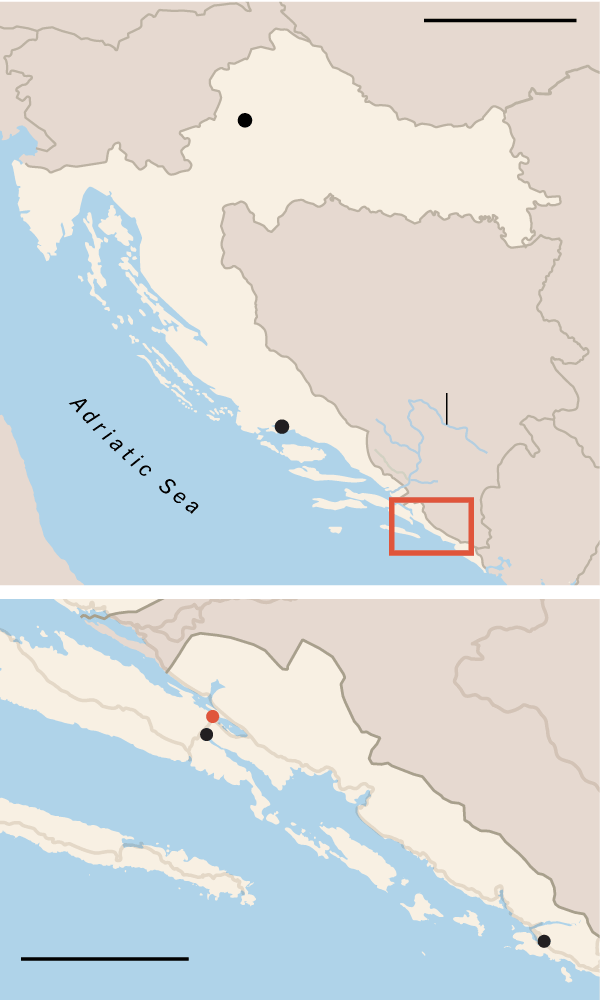

One early morning, as a mist shrouded the ancient wall that snakes around the hills overlooking the town of Mali Ston, Mr. Sare’s son, Tomislav, guided the family’s boat past the plastic markers bobbing in the shimmering blue waters and marking the collective’s oyster beds.

He stopped at one floating pontoon to pluck a string of European flat oysters, known as Ostrea edulis, from the water. He quickly shucked a dozen, topped them with a touch of lemon and smiled.

“Be careful, it is true what they say,” he said. “There is a reason Croatians have big families.”

The cultivation of oysters here stretches back centuries, to the days of Roman rule. Through wars and political upheaval, the harvesting may have been disrupted, but it never ended.

Oysters, like the people living along the Dalmatian coast, are survivors, Mr. Sare said. Around five million of the bivalves are pulled from the waters every year.

But they may soon face a threat from the swift and significant change to the ecosystem brought on by the headlong rush in the Balkans to embrace hydropower, often with little regard to the broader environmental consequences.

In a region still heavily reliant on coal, hydropower offers a clean and relatively cheap alternative energy source. Across the western Balkans, about 3,000 hydropower plant projects are underway or being planned — a 300 percent increase from just two years ago, according to a study by Fluvius, an ecological consultancy in Vienna.

The oyster farmers of the bay are most concerned about projects that would involve damming the Neretva River, which flows from Bosnia into Croatia and then empties into the bay.

A recent plan to build a dam in Bosnia on the river was scrapped at the last minute only when the Chinese company contracted for the project pulled out.

Local residents who depend on the bay fear that it is just a temporary reprieve. And they worry that other projects in Bosnia could be pursued.

The cultivation of oyster farms in Mali Ston Bay, part of the Adriatic Sea, stretches back centuries to the days of Roman rule.CreditZoran Marinovic for The New York Times

Bosnia is still split by ethnic division, divided into two entities — a Serb-run Republika Srpska and a mixed Muslim-Croat Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Political decisions are often made along ethnic lines, with little thought for the effect on the nation as a whole, much less adjacent countries.

Mario Radibratovic’s family has been farming oysters here for more than 500 years. Now a member of the oyster-farming collective, he worries about what will happen to the oysters if the hydrodam on the Neretva River is revived.

Oysters are only as good as the waters that feed them, he explained.

The unique blend of nutrients in Mali Ston Bay — the salt from the sea mixing with the fresh water from the rivers, with a rich bed of phytoplankton on the seafloor — creates the crisp, balanced flavor in the local oysters, prized since Roman emperors first funded farms here.

“The oysters need the fresh water from the river, and the proposed dam will cut that off and kill the ecosystem,” he said.

Even in the best of circumstances, an oyster’s “chance to live at all is slim,” Ms. Fisher wrote in her book “Consider the Oyster.”

Oyster eggs are devoured by the millions by other sea creatures, and a fertilized egg will develop only if the water is warm enough, above 70 degrees Fahrenheit. The lucky few develop into free swimming larvae, which float about as they like for a few weeks — each a “carefree youth,” as Ms. Fisher wrote.

Mr. Sare’s son, Tomislav, 22, explained what happens next on a tour of the family’s farms and the small island in the bay, which oyster lovers can rent for private parties.

The young oysters are captured in a net and after a year, he said, the ones deemed mature enough are cemented to a rope. For two years, they live hanging in the sea until harvest time.

The elder Mr. Sare started his seafood empire in 1980, when he opened his first cafe, not much more than a small shack on the side of the road that runs along the bay.

Mali Ston and the adjacent city of Ston were built as fortress towns during medieval times and became renowned for the 3.5-mile Great Wall that snakes around them. So in those days before the war, there were plenty of tourists to feed, Mr. Sare said.

But local businesses did not know how to cater to their needs, especially foreign visitors.

“In socialism, what you get is warm wine,” he said. But he paid attention to what customers wanted. He saw that Italians liked short coffee and the English black coffee.

“Americans want ice,” he said. So he bought what he believes was the first ice machine for miles around. The price for nearly everything on the menu was the same: $1.

Soon, he was raking in money, and the authorities started to take note. But he refused to give local officials a cut, and it cost him: When some vandals were caught near his cafe urinating on a monument to anti-fascist fighters, he was branded an enemy of the state and sent to jail.

A few years later, Yugoslavia would be convulsed by violence, and when war came, Mr. Sare took up arms with the Croat nationalists and was again briefly imprisoned for smuggling weapons.

He has since become one of the most successful restaurateurs in Croatia, expanding from his flagship restaurant in Mali Ston to outposts in Split, Dubrovnik and Zagreb.

And the draw at all the restaurants remains the oyster, so he hopes no dam or ethnic division ever affects their farming or flavor.

“Oysters know nothing of nationalities or ethnicities,” Mr. Sare said. “But politicians? They prosper on dividing people. So instead of protecting this heritage, they are still fighting about things stretching back to the Second World War.”