A pair of glasses. Comfortable loafers. A white shirt. Many of us have smart wardrobe staples for a reason — practical multipurpose pieces that save time and energy when considering what to wear every day. What these pieces never need to be, however, is ordinary. Nor should they come at the sacrifice of individual style.

Here are three independent European brands that have built reputations on making timeless crafted essentials with a fashion-forward edge.

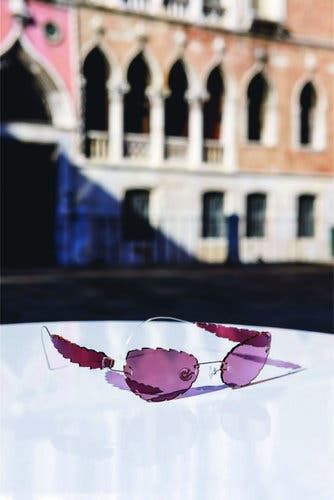

The Glasses

What do musicians like Elton John and Madonna, the fashion designer Rick Owens and the architect Norman Foster have in common? The answer: All are loyal fans of Micromega, a small, family-owned boutique hidden down one of Venice’s alleys that makes some of the most outrageous luxury eyewear in the business.

Micromega creates handcrafted designs that cannot be found anywhere else; feather-light, rimless spectacles; sunglasses with lenses that hang from a titanium wire (so they appear to be almost suspended); and frames from materials like buffalo horn and 14-karat gold. Each pair takes about three hours to create. And, according to the company, its patented frames — handmade as a single piece, without screws, glue or welding — are the lightest in the world.

“Our goal is to give clients something completely removed from what is on offer in the eyewear mass market,” said Ugo Carlon, a trained optician and designer, “where even luxury glasses can feel boring and the same as everything else on offer.” Mr. Carlon’s father, Roberto, founded Micromega, and his grandfather began the family eyewear business.

Prices start at around 330 euros ($365), and rise to as much as €2,400 depending on the materials and the level of customization. Lenses are also given special attention at Micromega’s workshop, about a two-minute walk from the store. (Both were damaged by the heavy flooding in Venice last month, but the company still is taking orders).

The name of the brand was derived from two ideas: the microprecision needed to create lenses and the mega, maximalist nature of artisanal design in Italy.

“Luxury to us is not the logo on the side of the frame,” Mr. Carlon said. “It is as much about researching around the prescriptions and needs of every customer as well as distinctive made-to-measure design. Eyewear is, after all, something most clients are medically dependent on.”

The Venice store continues to be the brand’s main sale point (it has no partners or stockists), though more than one-third of its clients are American and many now place recurring orders through the business’s website.

Next on the horizon, however? Possibly a second store, which would likely be in Italy’s fashion capital, Milan.

The Loafer

It was watching colleagues kick off uncomfortably stiff formal leather shoes under their office desks that first prompted Bo van Langeveld, who was working in private equity, to join forces in 2016 with Allan Baudoin, an Apple executive turned bespoke shoemaker. Together, they created Baudoin & Lange, a fashion footwear start-up with a focus on comfortable handmade dress shoes that could fit any foot.

After months of research, they settled on a signature style: an unlined flexible slipper-style loafer, in supple luxury materials and with a light, low sole and orthopedic-style handcrafted insoles. The Sagan model is so comfortable that the return rate is only 2 percent, Mr. Baudoin said.

“We are living in an age dominated by sneakers, which means people refuse to compromise on comfort with their footwear,” he said from the duo’s East London offices. “Many, though, still need a smart pair of shoes — and that’s where we come in.”

The bulk of the brand’s sales are made online, but every Sunday — and only on Sunday — the tiny shop in its headquarters (which happens to be a converted shoe factory) opens its doors to the public. Generally, about 250 people come to browse handmade styles, which start at around 300 pounds ($386).

The brand has now developed a strong following in Asia, particularly in China and Singapore, its founders say, and is stocked in stores like Selfridges in London and The Armoury in New York City. In late October, Baudoin & Lange also opened a temporary pop-up in the Burlington Arcade on London’s Piccadilly, in a store previously occupied by Chanel.

“We think unlined loafers are a timeless product, a chic and flattering style with cross-generational and geographical appeal,” Mr. van Langeveld said, adding that the brand’s production team had grown to 15 members and continued to quickly expand. Samples are made at the headquarters, but the bulk of the manufacturing is done in Italy.

“London has long been a world-leading hub for classic men’s attire, which is why we wanted to build our business here,” he said. “There is a lot of change in fashion. But the growth we have seen in the last three years couldn’t have happened anywhere else.”

The White Shirt

When the Turkish sisters Ece and Ayse Ege founded their Paris-based luxury house Dice Kayek in 1992, there was little question what their signature garment would be.

“I wear a white shirt almost every day and, like a canvas or block of clay, they tend to be the starting point to layer or explore my vocabulary as a designer,” Ece Ege said.

Over the years, the business has evolved to encompass both ready-to-wear pieces and couture, but sales of the white shirt still account for more than 30 percent of Dice Kayek’s total sales. Made from a range of materials including Swiss cottons, silks, washable poplins and structured blends that lend themselves to bold sculptural styles, the garment today is worn by fans like Naomi Campbell, Celine Dion, Amal Clooney and Zendaya. The best-selling style has a balloon sleeve, costing $850. (But the first offering, with Egyptian cotton appliqué roses blooming below the collar, continues to be sold, too.)

“We do not do make plain white shirts. Even the most basic has a twist and sense of luxury and detailing,” Ece Ege said. “The offer is quite wide, ranging from simpler designs toward demi-couture; pleated, folded, embodied and embellished with jewels.”

Today, many of the designs hang in the window of the first-ever Dice Kayek store, which opened in September in the St. Germain-des-Prés neighborhood of Paris, a stone’s throw away from the tables of Les Deux Magots and Café de Flore. Upstairs, against a striking green marble backdrop, customers can find both new and signature collections plus little plates of Turkish delight. Downstairs is a velveteen-lined fitting room for demi-couture, which the sisters say has proved particularly popular with Middle Eastern and Chinese clients.

“Online matters in today’s fashion business, but we also want people to know who we really are and receive a personal experience in the neighborhood where we live,” Ece Ege said. “Even with wardrobe staples like a beautiful white shirt.”