KINGSTON, N.Y. — More than 40 years after buying Eng’s, a Chinese-American restaurant in the Hudson Valley, Tom Sit is reluctantly considering retirement.

For much of his life, Mr. Sit has worked here seven days a week, 12 hours a day. He cooks in the same kitchen where he worked as a young immigrant from China. He parks in the same lot where he’d take breaks and read his wife’s letters, sent from Montreal while they courted by post in the late 1970s. He seats his regulars at the same tables where his three daughters did homework.

Two years ago, at the insistence of his wife, Faye Lee Sit, he started taking off one day a week. Still, it’s not sustainable. He’s 76, and they’re going to be grandparents soon. Working 80 hours a week is just too hard. But his grown daughters, who have college degrees and good-paying jobs, don’t intend to take over.

Across the country, owners of Chinese-American restaurants like Eng’s are ready to retire but have no one to pass the business to. Their children, educated and raised in America, are pursuing professional careers that do not demand the same grueling labor as food service.

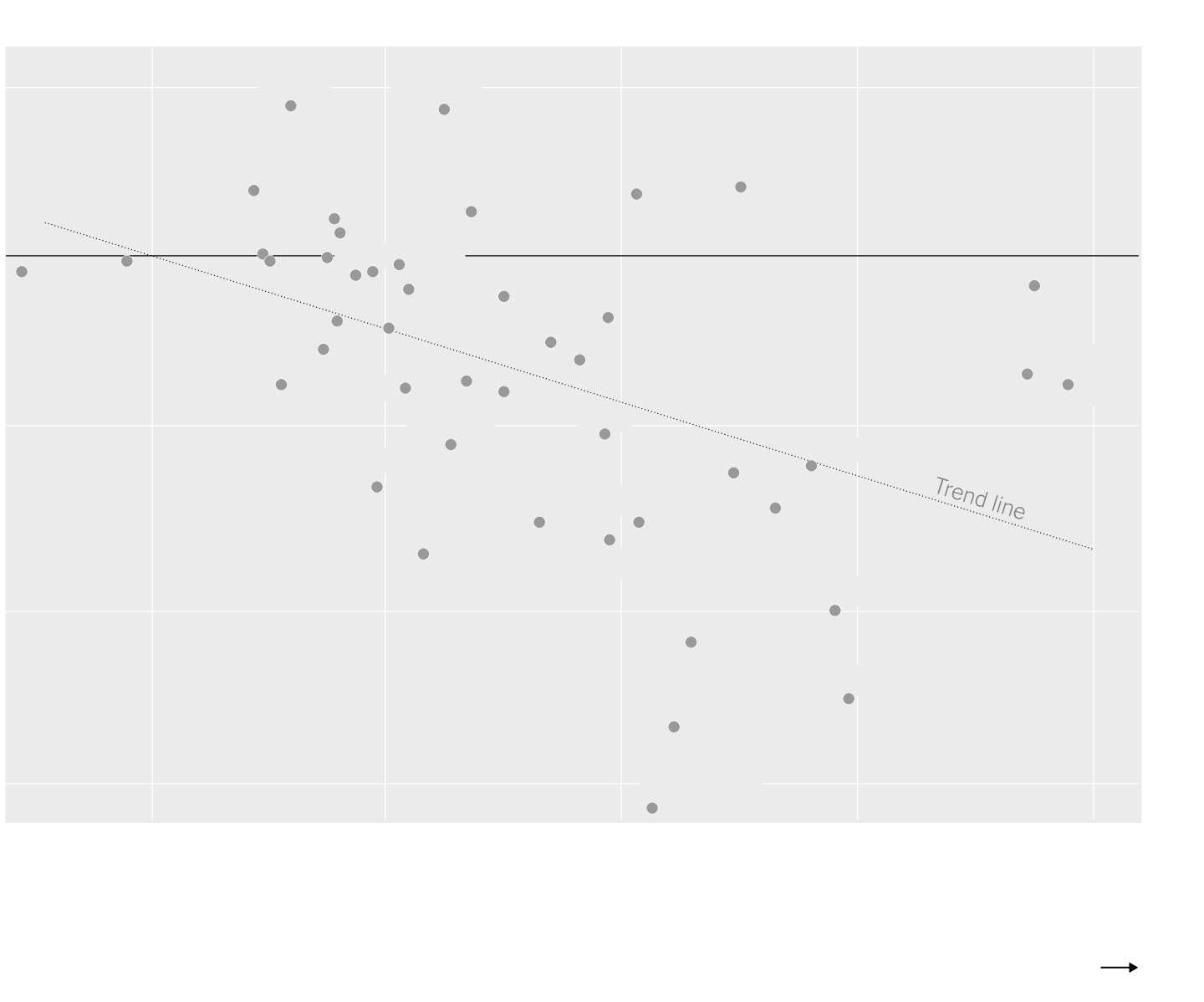

According to new data from the restaurant reviewing website Yelp, the share of Chinese restaurants in the top 20 metropolitan areas has been consistently falling. Five years ago, an average of 7.3 percent of all restaurants in these areas were Chinese, compared with 6.5 percent today. That reflects 1,200 fewer Chinese restaurants at a time when these 20 places added more than 15,000 restaurants over all.

Even in San Francisco, home to the oldest Chinatown in the United States, the share of Chinese restaurants shrank to 8.8 percent from 10 percent.

Chinese restaurants are losing ground in metro areas around the country

Share of restaurants in metro areas that are …

It doesn’t seem that interest in the cuisine has faltered. On Yelp, the average share of page views of Chinese restaurants hasn’t declined, nor has the average rating.

And at the same time, the percentages of Indian, Korean and Vietnamese restaurants — many of which were also owned and operated by immigrants from Asian countries — are holding steady or increasing nationwide.

The restaurant business has always been tough, and rising rents and delivery apps haven’t helped. Tightening regulations on immigration and accounting have also made it harder for cash-based restaurants to do business.

But those are not Chinese-restaurant-specific factors, and do not explain the wave of closings. Instead, a big reason seems to be the economic mobility of the second generation.

“It’s a success that these restaurants are closing,” said Jennifer 8. Lee, a former New York Times journalist who wrote of the rise of Chinese restaurants in her book “The Fortune Cookie Chronicles” and produced a documentary, “The Search for General Tso.” “These people came to cook so their children wouldn’t have to, and now their children don’t have to.”

The retirements of the restaurant owners also reflect the history of Chinese immigration to the United States. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act halted what had been a steady rise in people coming from China. It was not revoked until 1943, and large-scale immigration resumed only after 1965, when other race-targeting quotas were abolished.

China’s Cultural Revolution, an often violent social and political upheaval that started in 1966, prompted many young people to emigrate to the United States, a country that projected an image of freedom and economic possibility.

Mr. Sit left Guangzhou, in southern China, in 1968. He hiked, climbed and swam his way to Hong Kong, filling his pants with pine cones as an improvised flotation device.

“There was just no future,” he said. “The only way to get freedom and to get a good job was to go to Hong Kong.”

In 1976, he immigrated to the United States and started working at Eng’s, which opened in 1927. Although he had never worked in a restaurant, the heat from the woks was much less intense than what he experienced at a Hong Kong plastics factory where he had worked.

Unlike Mr. Sit, some immigrants had been chefs in China. They served Hunan and Cantonese foods on linen tablecloths to bejeweled, curious diners at places like Shun Lee Palace in New York.

“There was the golden age of Chinese cooking in America, starting in the late 1960s and early 1970s,” said Ed Schoenfeld, a restaurateur and chef who has worked in Chinese restaurants since the ’70s. “We started getting regional practitioners of fine regional cuisine to come to this country and do their thing.”

Mostly, though, the newly minted chefs cooked quickly and cheaply. They adapted their method of cooking to American tastes, developing dishes like beef chow fun, fortune cookies and egg drop soup, often brought home in the signature takeout containers.

“They were not precious,” Ms. Lee said. “These people did not come to be chefs; they came to be immigrants, and cooking was the way they made a living.”

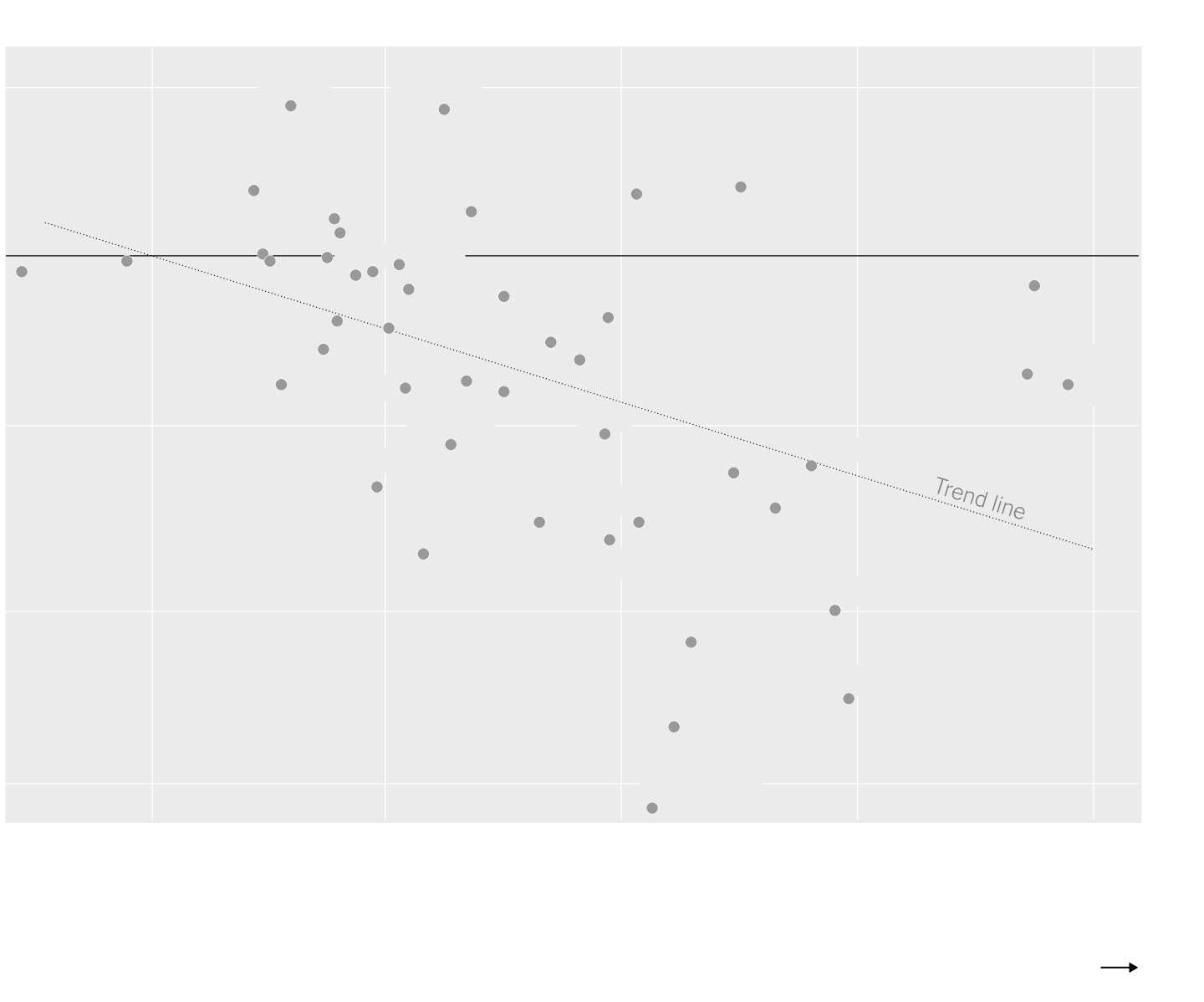

Other immigrant groups follow a similar pattern. With social mobility and inclusion in more mainstream parts of the economy, the children of immigrants are less likely than their parents to own their own businesses.

More economically mobile immigrant children are less likely to be self-employed

Change in the self-employment rate between first- and second-generation immigrants

El Salvador

More self-

employment

Yugoslavia

Philippines

Netherlands

Less self-

employment

South Korea

45th

pctile.

50th

pctile

55th

pctile

60th

pctile

65th

pctile

Average income rank for boys from poor families

MORE ECONOMIC MOBILITY

Change in the self-employment rate between first- and second-generation immigrants

El Salvador

Yugoslavia

Philippines

South Korea

45th

pctile.

50th

pctile

55th

pctile

60th

pctile

65th

pctile

Average income rank for boys from poor families

“In some ways, the children are regaining the status of the first generation that they have lost while migrating,” said Jennifer Lee, a professor of sociology at Columbia University and co-author of “The Asian American Achievement Paradox.” (She is not related to Jennifer 8. Lee.) “The goal has never been to continue those businesses.”

When they do become entrepreneurs, these children tend to work in industries like tech or consulting, rather than in food service or nail salons.

Most common fields for self-employed immigrants

In the past decade, some members of the second generation have also chosen to take charge of family restaurants. Nom Wah Tea Parlor, a New York dim sum restaurant that opened in 1920, has stayed a family business: first run by the Choy family, then the Tangs.

The 41-year-old owner, Wilson Tang, left a career in finance to succeed his uncle in 2011. Initially, his parents balked at his decision.

“As immigrants, it’s the only thing you can do; if it’s not restaurants, it’s a laundromat,” Mr. Tang said. “For me to choose to go back to owning a restaurant? That was tough for them to accept.”

Since then, Nom Wah has expanded: to another Manhattan location, to Philadelphia and to Shenzhen, China. On any given night, groups of guests wait for a table outside the Chinatown location for up to an hour, huddled in the bend of Doyers Street.

“I had this unique opportunity to preserve something that was from old New York,” he said. “I still work extremely hard. But I also know how to use marketing tools, like the internet.”

In a parallel effort, the team behind Junzi Kitchen, a fast-casual Chinese restaurant chain based in New York, recently raised $5 million to research and buy places like Eng’s, rebranding them with Junzi’s modern take on the cuisine.

“They are still going to have their usual beloved Chinese takeout services, but we are providing an upgraded version of that,” said Yong Zhao, the founder and chief executive.

But family-run Chinese restaurants are typically not being passed to the next generation. Some may close up shop, sell their businesses to other first-generation immigrants or move on and see their former storefronts become something else entirely.

Mr. Sit has not yet found the right person to run the restaurant, and has no immediate plans to close. “To take over Eng’s, you have to keep the heart in Eng’s,” he said. “You need to have a loyalty to the business, not just someone who thinks, ‘I’ll make one year, two years of money, I don’t care.’”

Ms. Sit feels more ready to retire than her husband. Normally talkative, he can be evasive whenever the family tries to bring up a successor.

“They’ll have to work hard,” she said, her eyes sparkling as she teased her husband, “like Tom Sit. Maybe then he’ll let them take over.”

If he ever actually does hand Eng’s to someone else, Mr. Sit will miss his customers, and miss running an operation.

But he is proud of what he built. He is proud that his daughters, American-born educated professionals, are working jobs they have chosen, jobs they love.

“I hoped they have a better life than me,” he said. “A good life. And they do.”