Bribing SAT proctors. Fabricating students’ athletic credentials. Paying off college officials. The actions that some wealthy parents were charged with Tuesday — to secure their children a spot at elite colleges — are illegal and scandalous. But they’re part of a broader pattern, albeit on the extreme end of the continuum: parents’ willingness to do anything it takes to help their grown children succeed.

As college has become more competitive and young adults’ economic prospects less assured, parents have begun spending much more time and money on their children — including well after they turn 18. Modern parenting typically remains hands-on, and gets more expensive, when children become young adults, according to a new survey by Morning Consult for The New York Times.

A significant share of parents, across income levels, say they’re involved in their adult children’s daily lives. That includes making doctor’s appointments, reminding them of school and other deadlines, and offering advice on romantic life, found the survey, which was of a nationally representative sample of 1,508 people ages 18 to 28 and 1,136 parents of people that age. More than half of parents give their adult children some form of monthly financial assistance.

Colleges now routinely have offices of parent relations. Companies including LinkedIn, Amazon and Google have hosted bring-your-parents-to-work days. Parents have applied to jobs on behalf of their children; lobbied their employers for a raise; and attended job interviews with them. They have called their children’s roommates to resolve disagreements or to check on their children’s whereabouts.

For certain members of the superrich, the tactics have been extraordinary — nobody would equate accusations of bribery with helping a college-aged child with homework or a job application. The factors driving most parents, researchers say, are widening inequality, the growing importance of a college degree, and the fact that for the first time, children of this generation are as likely as not to be less prosperous than their parents.

“It’s the same thing but on a much different level,” said Laura Hamilton, author of “Parenting to a Degree: How Family Matters for College and Beyond” and a sociologist at the University of California, Merced. “It’s really hard for parents to understand why you wouldn’t do anything you could do to assist your children. If you have the influence, the connections and the money, it’s not surprising to me that the parents made these choices.”

Even more typical parental involvement can backfire, many experts say, by leaving young adults ill-prepared for independent adult life, and unable to succeed at the schools and jobs their parents helped them get to.

“When one is hand-held through life, they don’t develop a sense of self-efficacy and life skills,” said Julie Lythcott-Haims, the author of “How to Raise an Adult: Break Free of the Overparenting Trap and Prepare Your Kid for Success” and a former dean of freshmen at Stanford. “This sense among parents that I’ve got to get my kid to the right future is overlooking the fact that your kid has to get themselves there.”

It’s a continuation of the kind of intensive parenting that has become the norm in the United States. Today’s parents, especially mothers, are spending more time and money on their children than any previous generation — on things like lessons, tutors and test prep. Many parents’ anxiety only intensifies after 18, when children start the education and jobs they’ve been preparing for.

“Professional helicopter parents are really focused on using education to get their children into a professional career,” Ms. Hamilton said. “Their goal is basically to prevent their children from ever making a mistake.”

This kind of behavior is most prevalent among privileged parents, those with collegiate experience and wealth. In places with the biggest gaps between the rich and the poor, rich parents spend an even larger share of their incomes on their children, a recent paper found. The bribery scandal shows how far some parents will go — in one example, parents were accused of paying $1.2 million to help get their child into an Ivy League college.

More commonly, financial help comes in the form of tuition or rent payments. Parents used to spend the most money on their children during high school, according to Consumer Expenditure Survey data analyzed by the sociologists Sabino Kornrich and Frank Furstenberg. But now they spend the most before age 6 and after age 18 and into children’s 20s.

The increases in later years are because so many more children are going to college, which has become much more expensive, Mr. Kornrich said. Also, about a third of children this age still live at home. In the new survey by Morning Consult and The Times, about two-thirds of those who lived with their parents said it was because they could not afford to live on their own or were still in school.

One in three parents said they gave their 18-and-over children $100 or more a month, and 44 percent of those with children in college made tuition or loan payments for them. When asked at what age people should be financially independent from their parents, the largest share of young people said 25 to 28.

Recent research shows that even parents who can’t afford to give their grown children money increasingly provide them with significant support of other kinds. In the survey, wealthier parents were more likely to report giving their children money than less affluent ones were, but many nonfinancial measures of parental support remained consistent across income and education levels.

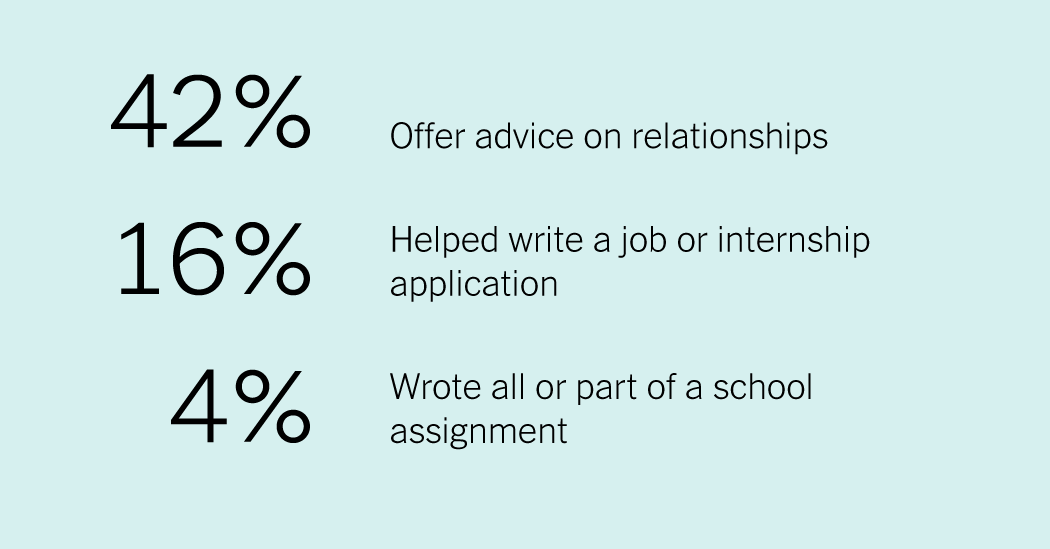

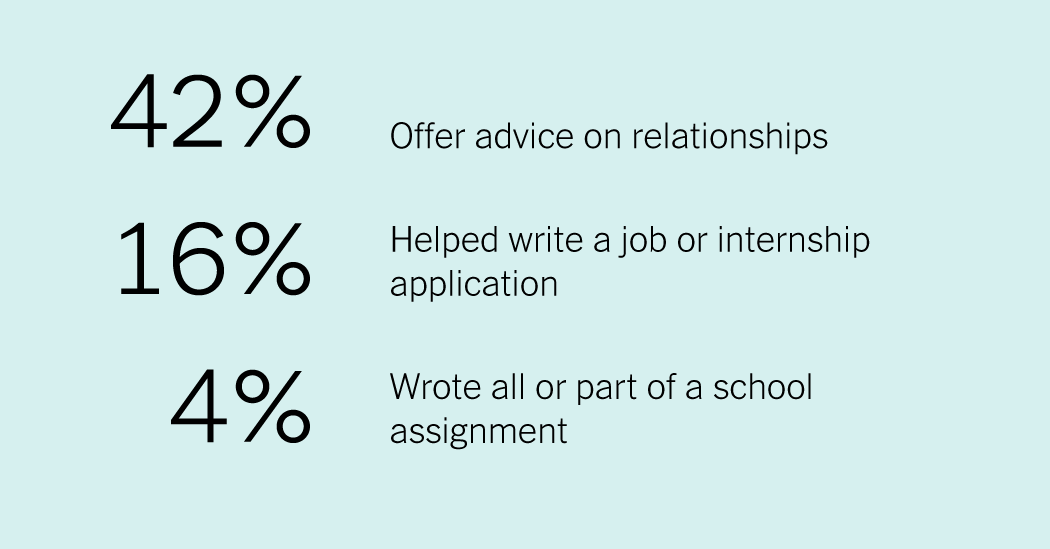

For example, three-quarters of parents with children ages 18 to 28 said they had reminded their children of school and other deadlines they needed to meet — whether the parents reported a low or high income. Four in ten parents, across income and education levels, said they offered romantic advice to their children.

Parents gave their children less money, professional advice and job application help as they got older. Romantic advice, however, did not taper off.

Parents reported a more engaged relationship with their grown children than they once had with their own parents. They said they spent more time with their children, communicated with them more often and gave more advice than their parents had when they were the same age. Eight in ten said they were “always” or “often” in text message communication with their adult children.

This period of life has become so established that researchers have given it a name: emerging adulthood. In some ways, it has become harder to be an adult. Wages have stagnated, while the cost of college, homes, health care and child care have climbed. This generation has record student loan debt and low homeownership rates.

“There’s no room for risk,” Ms. Hamilton said. “It’s not like in 1970 when you could screw around a little because every extra year of college didn’t cost you an arm and a leg and not graduating wasn’t incredibly risky.”

Cultural changes play a role, too. White, native-born American families previously had an expectation that adult children should separate from their families, said Karen Fingerman, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin who studies the relationships between young adults and their parents. But that’s changing as families are remaining closer throughout their lives, with more intergenerational support. Technology has made it possible for parents and grown children to stay in constant contact. Young people are marrying less and later, and parents are having fewer children, so they have more attention and money to devote to each one.

There are many benefits to parents’ increased involvement in their grown children’s lives. Ideally, she said, the relationship goes both ways, with adult children providing support and assistance to their parents, too. About a quarter of people 25 to 28 who lived at home said it was because their parents needed help.

“There’s more mutual companionship,” Ms. Fingerman said. “This is the most important relationship in their lives on both ends.”

But experts say there’s a line between supporting young adults and stifling their growth. Ms. Lythcott-Haims compares it to teaching children to drive — the parent starts in the driver’s seat, but the goal is to end up in the back seat. “You can’t just arrive them at the future you want for them,” she said. “They have to do the work to build the skills.”

Research has shown that children of hyper-involved parents are often more successful at navigating college and finding good jobs — but that they are less self-reliant and more likely to face anxiety or depression.