Browned palm leaves fan over the white-sand beaches of Caneel Bay Resort. Peeling paint buckles on the exterior walls of roofless cabins. Inside, white curtains, still knotted, drape like ripped cobwebs from windows, and mold-matted mattresses sag without their frames. A back door swings wide.

Long considered the crown jewel of St. John, a small emerald island found among the U.S. Virgin Islands and cut with curved bays and set against the turquoise waters of the Caribbean, the 170 secluded acres of Caneel Bay once drew presidents, movie stars and literary icons — from John Steinbeck and Lady Bird Johnson to Meryl Streep and Mitch McConnell.

More than 15,000 people annually visited the property nestled within the Virgin Islands National Park and home to a handful of endangered species. The four-star eco-resort, established by the Rockefeller family, was one of the first in the United States.

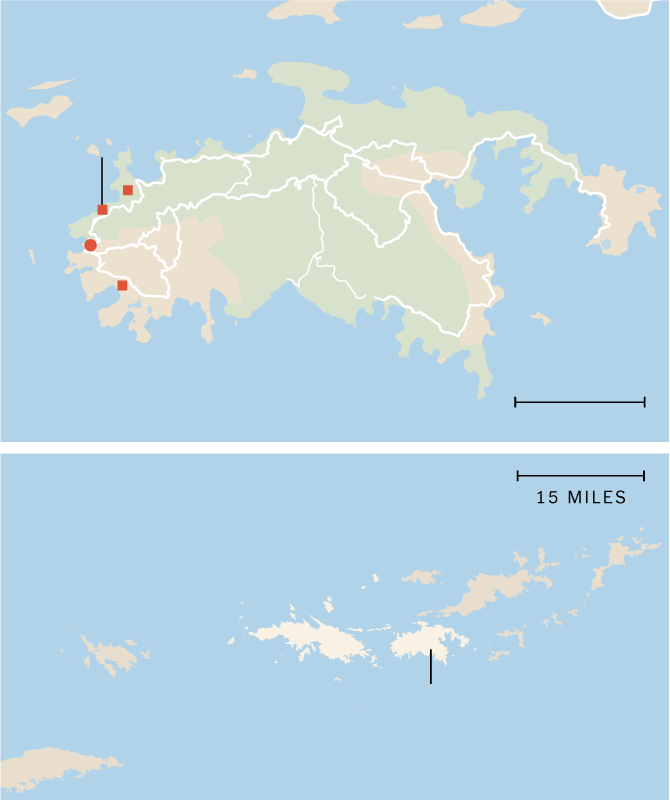

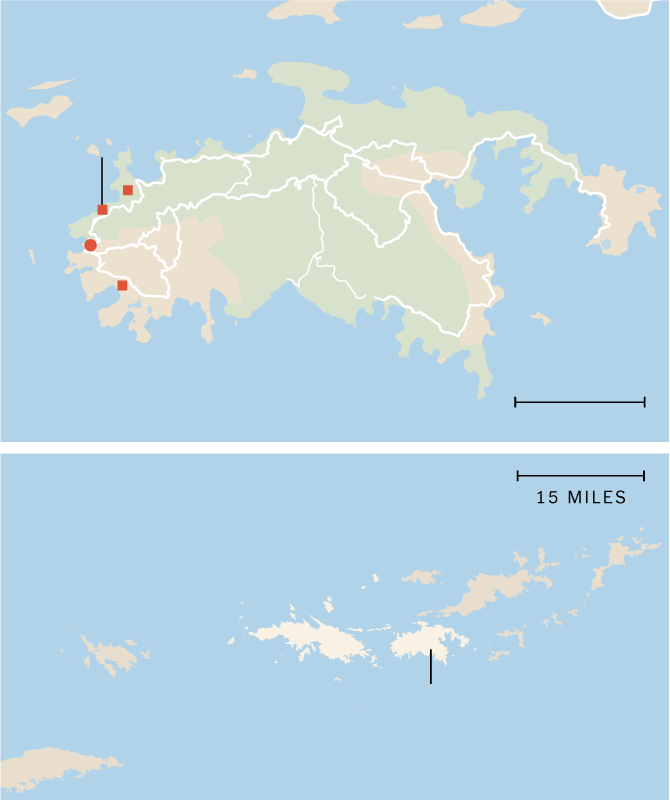

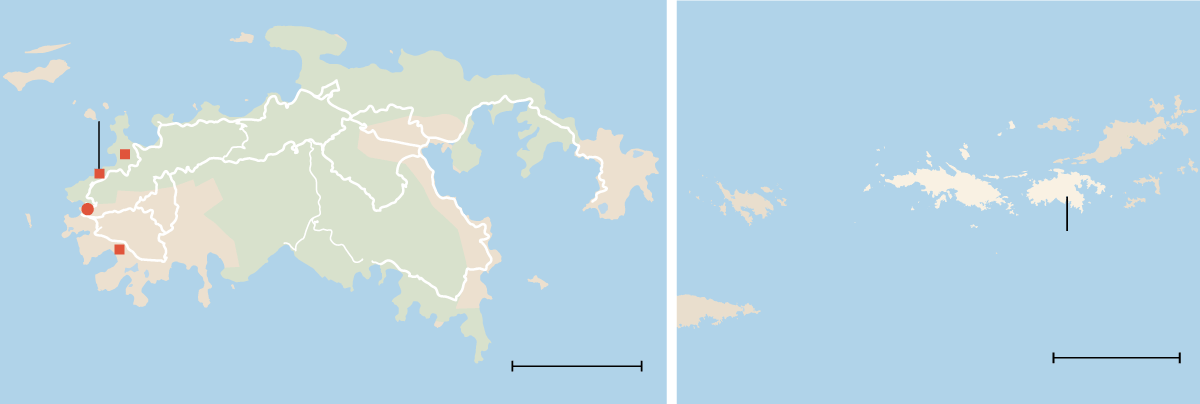

Lovango Cay

Honeymoon beach

Caneel Bay Resort

VIRGIN ISLANDS

NATIONAL Park

The Westin

St. John Resort Villas

Caribbean Sea

Atlantic Ocean

U.S. VIRGIN

ISLANDS

British

Virgin

Islands

ST. THOMAS

Puerto

Rico

Caribbean Sea

Atlantic Ocean

British

Virgin

Islands

Lovango Cay

U.S. VIRGIN

ISLANDS

Honeymoon beach

Caneel Bay Resort

VIRGIN ISLANDS

NATIONAL Park

ST. THOMAS

Puerto

Rico

The Westin

St. John Resort Villas

Caribbean Sea

Caribbean Sea

“It was a first-class experience without the pretentiousness of the rest of the world,” said Bob Rice, a guest from Needham, Mass., who stayed at the property with his family eight times. “You just got nature at its best.”

Two weeks in September 2017 changed that. Hurricanes Irma and Maria — both Category Five storms — flogged St. John, ripping apart structures and flooding what remained.

Even as other accommodations in the region have reopened, Caneel Bay remains in tatters. Those who have ventured inside recall a newspaper on the front desk dated September 2017 — just before the first storm. Scheduled weddings marked the chalkboard, they say, and rats could be seen scurrying across the wine cellar floor.

While the hurricanes ripped apart the resort’s infrastructure in a matter of hours, the storms’ lingering aftermath laid bare its long-festering problems, which include an unorthodox land-use agreement with the federal government, possible environmental contamination that predated the storms and contentious relationships between the staff and management. Together, they have stalled the resort’s reconstruction and hurt the island’s economy.

Caneel Bay’s future is tied up in a dispute between its owner, CBI Acquisitions, which took over the resort in 2004, and the National Park Service, which owns the land where Caneel Bay sits. CBI Acquisitions says they cannot afford to rebuild unless they get an extension of their right to control and use the resort property from the Park Service.

In turn, the Park Service says that the agreement needs to be renegotiated and that it needs to complete environmental testing — on hold since 2014 — to determine the extent of mercury, arsenic and other hazardous chemicals previously found on the property, as well as the cost of the cleanup.

‘The first ferry over’

Bob Natt and his wife, Helen, honeymooned at Caneel Bay in 1971. As their family grew, they spread to several cabins, staying some 30 to 35 times over 46 years.

“Getting a Christmas cottage on Caneel Bay was like something you put in your will — it was that hard to get,” said Mr. Natt, who lives in Easton, Conn.

To stay in its 166 simply furnished cabins, guests spent an average of $727 a night — and up to almost $2,000 for Christmas in 2017.

Mr. Natt, 71, has maintained contact with management. “I said ‘the day you open, I want to be on the first ferry over’.”

In 2017, less than two weeks after employees waved the last boatload of guests from the dock, ahead of an annual eight-week hurricane season closure, Hurricane Irma hammered St. John and neighboring St. Thomas, splintering trees, ripping off roofs, twisting metal frames and collapsing walls.

Twelve days later, Hurricane Maria swallowed what little remained — including the initial repair efforts — dumping up to three feet of rain atop the devastation.

At other hotels, the push to rebuild was almost immediate. The Westin St. John Resort Villas, one of the few other resorts on St. John, employed staff to help with the cleanup, which took 16 months. The resort fully reopened to guests last February.

At first, Caneel employees — who made up seven percent of the U.S. Virgin Islands’ total employment in the hotel and restaurant sector, “putting Caneel on par with Walmart in terms of the number of jobs created in a state by a single employer,” according to a Congressional white paper — expected they would be similarly involved in their resort’s clean up, as they had with previous storms.

But this time, hundreds of workers found themselves unemployed. Unionized employees, some who had worked on the resort for decades, received termination letters by mail.

“The whole community is hurting,” said Theresa Germain, a housekeeper who retired months before the storms and worked on the resort about 35 years.

But no rebuilding began.

CBI Acquisitions, a limited liability company based in Connecticut and created to purchase the resort, has the rights for land use and occupancy until 2023. Gary Engle, the resort’s principal owner, has refused to rebuild without an extension of those rights, saying it is not worth the investment of about $100 million to rebuild most units and install new electrical wiring and plumbing, among other tasks.

“Lack of clarity is the major problem with the resort right now,” Mr. Engle said in an interview. “Because without fixing the uncertainty, there’s no money that’s going to be invested in this property.”

The destroyed resort is an inescapable sight on such a small island. Only the main entrance has been repaired. For $20, visitors can take a golf cart ride from there to Honeymoon Beach, the only beach out of seven associated with the resort that has reopened.

The golf cart trundles over a potholed path, jagged with bare pipes and winds past an eerie landscape of deserted cabins, overgrown brush and felled trees.

The Rockefellers arrive

In 1952, while cruising along the Caribbean, Laurance Spelman Rockefeller, the grandson of the oil tycoon and a successful venture capitalist and conservationist, docked at Caneel Bay, where he bought the stock of an existing resort.

Mr. Rockefeller and another developer soon began buying real estate around the resort. Despite reservations from some residents, they planned to create a national park.

Eventually, Mr. Rockefeller turned over more than 5,000 acres to the National Park Service, which today owns almost two-thirds of the island.

In 1956, Mr. Rockefeller opened an environmentally focused resort in the heart of the newly created Virgin Islands National Park — on land he kept for himself.

Theovald E. Moorehead, a native of St. John and local lawmaker who successfully petitioned Congress to prevent islanders’ land from being condemned for the park, grew concerned over changes he witnessed on the island.

“We like tourists but we will not sacrifice ourselves to make this a happy place for tourists,” he wrote in 1958. “What we want is a happy island — happy for everyone — including ourselves.”

As the years passed, the Caribbean, a popular destination for American travelers accustomed to luxury hotels, saw an influx of big-brand hoteliers and cruise lines; Many benefited from offshore tax incentives from the U.S. Virgin Islands Economic Development Commission, an organization geared toward aiding companies establishing themselves in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Caneel Bay Plantation, as it was then called, offered an alternative experience beyond chain brand amenities — with cabins just footsteps from the water, and an informal communal teatime where guests mingled each day on the veranda.

The Rockefeller family donated the property to the Park Service in 1983, but based on a vaguely written legal condition, they continued operating the resort through one of their nonprofits, untethered by typical National Park standards.

The “retained use estate” contract — now the only such commercial agreement across the Parks Systems — was 13 pages long, bare bones compared to current park leases, and immediately caused confusion. Within a year, the Interior Department, which oversees the Park Service, explained the parks had “very little authority” on the property, based on “the expansive nature” of the Rockefellers’ reserved rights.

The resort changed hands several times, eventually causing even Mr. Rockefeller concerns. He wrote to the Park Service director in 1988: “It is my sincere hope that you would not consider granting any request to extend the Retained Use Estate at Caneel Bay.” He added that his “intention and expectation” was for the R.U.E. to expire by 2023.

An asbestos pipe, stalled testing and no answers

Caneel Bay Resort was one of the region’s few eco-lodge resorts, featuring a reverse osmosis water plant and environmentally friendly upgrades. And the land agreement with the Park Service — which receives no payment for use of the federal property — along with long-extended benefits from the Economic Development Commission, made the resort’s business position enviable.

Shortly after CBI Acquisitions took over the land agreement in 2004, Mr. Engle, started looking for ways to extend the R.U.E.

“That was an essential part of the transaction,” Mr. Engle said of the initial purchase. But despite the benefits, he said it wasn’t all positive, particularly the lack of clarity around what would happen after the agreement expired in 2023.

A bill passed by Congress in 2010 would enable a 40-year extension, following routine environmental testing, and contingent on the company relinquishing the mandates of the R.U.E.

Initial environmental tests were conducted in 2012 and 2014; but while some results were made public, those referring to potential environmental problems were not.

Those unpublished assessments, reviewed by The Times and National Parks Traveler, a news website covering the parks and other protected areas that provided The Times with some documents, noted, among other concerns “a release of hazardous substances or petroleum products” throughout the property, including excessive amounts of mercury and arsenic.

A pipe with “approximately 30 percent asbestos,” considered a high amount, was also found, and an employee told the assessors that more pipes existed.

No health problems have been documented, but the Park Service, which requested the tests as part of departmental policy, noted that more tests were needed. The public was never alerted, and the follow-up tests never happened.

Caitlin Klevorick, a CBI Acquisitions spokeswoman, said by email that the company believed that if any potential environmental problems exist, they resulted before CBI Acquisitions became landholders.

“Caneel Bay was fully committed to and did operate the resort to ensure guests’ safety,” she said.

Michael Litterst, acting chief of public affairs for the Park Service, declined to be interviewed, noting “both pending legislation and potential litigation.”

But Stephanie Roulett, a Park Service spokeswoman, said by email that the agency had tried to get on the property multiple times and had not been granted access. She said that while they could implement a “legal procedure,” they had “thus-far not significantly pushed back.”

A series of letters between Mr. Engle and the Park Service, obtained by The Times, illustrates negotiations at loggerheads.

In April 2019, Mr. Engle sent the Interior department a letter claiming the right to “immediately and automatically” take over the property unless the government paid $70 million and assured indemnification “from all environmental liabilities.”

The agency rejected Mr. Engle’s ultimatum, repeating a request for additional environmental testing.

Ms. Klevorick, the resort spokeswoman, said the company is “committed to further cooperation with the NPS in the next phase of an environmental site investigation.”

The storm before the storms

Even before the hurricanes forced the resort to shut down, some longtime employees had become increasingly frustrated.

Ms. Germain, the housekeeper and local union representative, said when she started working at the resort in the 1980s, staffers had a sense of pride but that diminished under new management.

“As time passed it got a dose of bad management,” she said. “They treated us really poorly — really bad down to the last.”

Employees who had been full-time said that their hours declined in favor of seasonal workers. (Ms. Klevorick said that CBI Acquisitions “always prioritized” full-time employees over seasonal workers.) Management also instituted a security policy in which it checked employees’ bags before they left the resort each day.

Sheryl Parris, who has been president of the local union representing Caneel Bay since 2012, said that the “very insensitive” practices evoked hard feelings.

Caneel also attempted to reduce its full-time staff, successfully negotiating in April 2017 with the Economic Development Commission to decrease the minimum number of employees with full-time status to 230, a reduction of almost 100 people.

Additionally, despite continuing to collect local tax breaks — including a 90 percent income tax exemption and full exemptions from other taxes — the resort did not actually employ most of their workers year-round. All but a few dozen were let go each year for a six-to-eight week hurricane season closure, beginning in 2009.

Other resorts on nearby islands have also implemented such closures, but previous owners of Caneel Bay had never done seasonal layoffs. At a public hearing the day the work force agreement was announced, one commission member expressed reservations about the habitual layoffs but the resort continued the practice.

‘I want to do the right thing’

Months after the storms, and with the resort moldering on site, Stacey E. Plaskett, the U.S.V.I. delegate in Congress, introduced a new bill allowing a 60-year extension on the R.U.E. to coax the owners to rebuild. Missing from the bill’s text: any mention of required environmental testing.

Some resort staff and the greater St. John community felt excluded from the process and the bill was not well-received, particularly by some former employees who say they still never received paychecks for their last two weeks of work. Ms. Klevorick said the company was unaware of any employees who had not received payment “but recognizes that immediately following the storms it was very chaotic.”

As Ms. Plaskett’s approval rating plummeted on St. John, her working relationship with Mr. Engle also deteriorated; he appeared uninterested in working with the community, she said.

Mr. Engle acknowledged community frustration.

“Maybe when I was down there I didn’t handle it as well as I could have,” he said. “I want to do the right thing for the employees, I want to do the right thing for the community and the Virgin Islands.”

Then, about a year after the storms, Mr. Engle invited former employees and others onto the resort property for a meeting. Several people there recalled him framing the rebuild as contingent on the bill’s passage. Ms. Parris recalled employees offering to return and clean up, but instead, she said of the company: “They were waiting for that bill and so they kept all the employees waiting.”

The bill died. Ms. Plaskett said she has no plans to introduce new legislation.

Negotiations between CBI Acquisitions and the Park Service are ongoing. Last month, the company submitted a proposal to the service, and Ms. Roulett said earlier this month that the agency was currently drafting its own.

‘$60 and you’re doing good’

The loss of tourism has had lasting effects on bars and restaurants, as well as cabdrivers, who made the bulk of their money taking guests to and from dinner to places like ZoZo’s at The Sugar Mill, an Italian restaurant once located at Caneel.

“Before, everybody was making something,” recalled Everett Wilkinson, one cabdriver. “Now everyone is hustling for whatever they can make. It’s why most people on the island have two or three jobs — just to survive.”

Previously, he often brought in $200 a day. Now, “$60 and you’re doing good,” he said. “The taxi service right now is down to nothing. We’re sitting right by the dock, and we’re not moving.”

Although Mr. Engle insists that the rebuild has been stalled by uncertainty about what will happen to the property in 2023, court documents filed by certain underwriters at Lloyd’s of London, suggest that the company was “grossly underinsured.”

So far the company has received $32 million for a claim of total devastation following Hurricane Irma — although the resort’s insurable value was more than twice that.

Mr. Engle said that the groups are currently arbitrating the company’s claim for a separate payout for Hurricane Maria, saying that the damage incurred by the second storm was distinct from the first — a claim the insurance company has contested. Arbitration is scheduled for April.

Around the time that he was promoting Ms. Plaskett’s bill to former employees in 2018, Mr. Engle said in an interview with a local reporter that he was in a position of power with an insurance payout that did not require him to rebuild.

“I could take that money and walk away, or I can take that money and reinvest and maybe put up a little more capital and turn this into something special,” Mr. Engle said. “Without Caneel Bay, St. John is going to implode.”

Recalling that interview, Mr. Engle said that “as a matter of economic fact” the resort brought thousands of visitors to St. John and that “the amount of money that was spent by Caneel guests both at the resort and in the shops and the restaurants in Cruz Bay was very significant for an island with several thousand people.”

“I was basically stating the obvious,” he concluded.

‘We didn’t have hurricanes like this’

A new environmentally sustainable resort is set to open in early 2021 on Lovango Cay, an island belonging to St. John and a 10-minute boat ride from Caneel Bay.

Mark and Gwenn Snider, who own resorts in Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, are designing the solar- and wind-powered resort.

“We’re really hoping to just have people do what they do best,” Mr. Snider said. “ Come down, help the economy — not to impose on the community — and travel with just their footprints.”

The hurricanes that battered the Caribbean in recent years have brought to light the region’s deeper issues with economies overly dependent on tourism. On St. John, all of those issues have come to a head.

“Keep in mind this has never happened in the Virgin Islands before,” said Ms. Parris, the union president. “We didn’t have hurricanes like this. We had hurricanes where trees would fall, but we went back to work. ”

And still, Caneel Bay’s devoted patrons hope one day they can return.

Mr. Natt, the longtime guest, said his family has returned to the region three times since the storms, though not to St. John.

“We have not found anything on the Caribbean that has been as good,” he said. “Without Caneel, the grandkids didn’t want to go.”

Emily Palmer, a journalist based in New York, contributes frequently to The New York Times and covers courts and crime.