How does a design success come to feel like a flub? Is it when a clear vision doesn’t find the right platform? Is it when a ballyhooed debut limps onto the sales floor? Or is it just a matter of a trial balloon looking like it’s leaking air?

These thoughts are brought to mind by the reboot of J. Crew under the direction of Brendon Babenzien, the former design director at Supreme who once did for the hoodie generation what J. Crew had done for its dads.

Supreme, that is, defined a landscape. Mr. Babenzien set the tone at Supreme. The Supreme marketing strategy may have been built around manipulated scarcity and drops, but the design chops behind it were Mr. Babenzien’s and were real.

During his decade or so at the label, Mr. Babenzien toyed with proportions. He understood messaging graphics. He got that you can subvert gender stereotype through such simple means as taking a hue traditionally associated with the My Little Pony set and effectively rebranding it as millennial pink.

In its own way, J. Crew once did something similar, though for a very different cohort. Where Supreme owned streetwear, J. Crew had a lock on the business bros. What had begun in 1947 as a preppy catalog house became, under the later leadership of Millard Drexler, a phenomenally successful purveyor of affordable, trend-conscious work and leisure wear. Remember the Ludlow suit? Of course you don’t.

In its day — which is to say roughly 15 years ago — this rejiggered version of a traditional office uniform transformed our relationship to suiting. When it first came along, the Ludlow challenged the designer market by being a trim and neutral, though not Goldilocks-boring, version of a suit that. if its label read Zegna, would have sold for 10 times the price. The Ludlow’s design reflected a variety of changes in men’s wear, among them a growing interest in male fashion, an attendant boom in the market and an interest in physical fitness that would reach its thirst trap apogee with the advent of Instagram.

In its heyday, J. Crew answered to the needs of a marketplace in another way. Where men’s wear had traditionally been banished to department store basements, J. Crew brought in specialty boutiques like the Liquor Store that made clothes shopping feel like dropping into some exclusive club. With the designer Todd Snyder at the helm, it pioneered heritage collaborations with brands like Red Wing, Thomas Mason, Blackstock & Weber and Timex.

J. Crew became cool — or at least as cool as a mass market label can be — and, in this, it owed a clear debt Ralph Lauren, the granddaddy of them all. When it comes to making brand magic, no one has ever topped a man who, just over a half century back, gambled on producing a line of splashy neckties. Mr. Lauren’s early bet produced a jackpot payoff, rendering him not just a billionaire but a household name and the acknowledged kingpin of retail as theater.

No matter that the Polo image was a patchwork of American archetypes, sartorial pastiche and hokum — Piping Rock Club meets High Plains Drifter. It brought shoppers into stores and made cash registers sing. While there are no cash registers anymore, there remains an urgent need for ways of turning mythologies into mercantile wizardry as designers struggle to lure mass market consumers out of their pandemic caves. We need, in other words, another Ralph Lauren to create a new Magic Kingdom. For a moment it looked as if Mr. Babenzien could be that guy.

The field was wide open. Back from a 2020 bankruptcy brought on by a series of business missteps that left the company saddled with debt, J. Crew is aiming to regain its cool at a time when, in the words of Mobilaji Dawodu, the fashion director of GQ Style, cool is mainly in our phones.

“Everything is cool now, so nothing is cool,” Mr. Babenzien said last month at the J. Crew headquarters near the 9/11 Memorial. “What’s more interesting to me is being comfortable being yourself.”

That’s all good in the abstract. Yet if the skyrocket trajectory of Virgil Abloh’s career at Louis Vuitton and Off-White taught us anything, it is the difficulty of finding comfort and self-assurance when we are barraged every waking hour by noisy and often conflicting inducements to be anything but what we are not. Design may no longer hunger for monolithic figures like Mr. Lauren, but it will always need pathfinders.

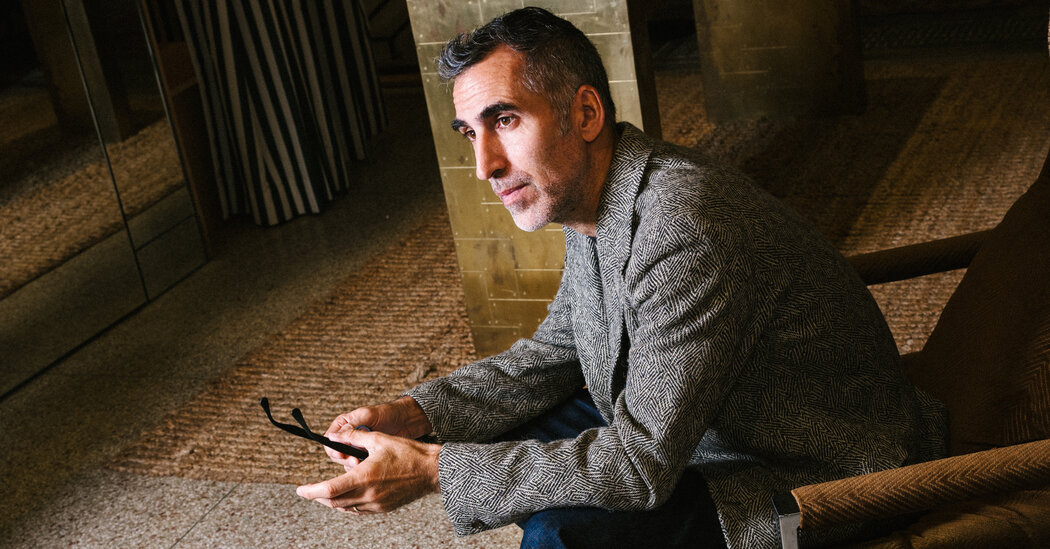

Mr. Babenzien, 50, could easily be that person. In fact, he has the biography (lifelong skateboarder and surfer, early hip-hop generation Long Islander with ample Manhattan club-kid cred) and the design résumé to make something great out of this J. Crew outing.

And it is true that he scored a success straight out of the gate with a pair of Giant Fit Chinos — cuffed khakis trousers with a 10-inch diameter hem that flew out of stores the minute they hit. The concept shop Mr. Babanzien and his wife, Estelle Bailey-Babenzien, designed in conjunction with her DreamAwake studios in the former Saxon + Parole space on the Bowery has precisely the chill and clubby elements (coffee bar, Brazilian Modernist furniture, collectible art books, capsule collections of “vintage” J. Crew items, a sound system playing Marvin Gaye) needed to make bricks-and-mortar shopping seem like an adventure again.

Yet, instead of a broad design statement, Mr. Babenzien appears to have settled for tweaking: shifts in palette that render Fair Isle pullovers in skater pastels; carpenter pants produced in corduroy; woolen barn jackets in heathery plaids; funky shorts in nautical prints based on paintings by the artist Willard Bond; suits in novel shades of black; wardrobe staples like hoodies manufactured in the solid-gauge cottons that were a given before mass market labels like J. Crew traded quality for profit.

Just as concerning is how tough it is to find the new Babenzien J. Crew men’s wear at the label’s other outposts around Manhattan, where his designs are shelved or hung in such a way that finding them is like embarking on an Easter egg hunt.

It is not just that his collection is salted among generic offerings. It is that, if J. Crew is to succeed again in a marketplace crowded with, among other things, its own alumni (Mr. Snyder, in particular used a recipe he perfected as a hired hand to produce his own label), it’s going to require a bolder statement of intent, a bit of Ralph Lauren special sauce, an element of whatever it was that had people lining up for hours on Lafayette Street each Thursday morning for Supreme’s latest drop.