It’s easy to imagine lounging in the garden at the sprawling villa of Julia Felix, a savvy Roman business woman who lived in the ancient Roman city of Pompeii in the first century A.D. There would have been wine to drink, and fresh figs, apricots and walnuts to savor. The warm sea breeze would have blended the dry scent of cypress and bay leaves with the stench of rubbish and excrement from the street, and the gurgle of water in the baths would have been occasionally drowned out by cries from the crowd in the 20,000-seat amphitheater nearby.

On a recent weekday morning, a slow-moving line of tourists snaked through the elegant estate, admiring what’s left of the elaborate frescoes, deep-set dining room and marble pillars. Nearly 2,000 years have passed since Pompeii and its surroundings were buried under ash and rock following the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D. But this estate, which recently reopened following extensive restoration, appears much as it would have looked when Julia Felix still welcomed her paying guests.

The renewed Felix estate is just one outcome of a multiyear project that was meant to save Pompeii from a crisis caused by decades — even centuries — of underfunding and mismanagement. The Great Pompeii Project, scheduled to wrap up the end of this year, has secured many of the site’s threatened buildings, led to important discoveries and significantly improved the experience for tourists.

But challenges persist. The Archaeological Park of Pompeii — as distinct from the adjacent modern Italian city of Pompei — is set to receive a record-breaking number of visitors this year, guards are in short supply, and everyday maintenance of the 163-acre archaeological site remains staggeringly expensive. Some observers worry that Pompeii could slide back into disrepair.

A troubled history

It’s a state that the ancient city knows all too well. Since concerted excavations began in the middle of the 18th century, Pompeii’s rich homes, tombs and public buildings have been plundered by looters, exploited by profit-hungry private excavators, and (in some early cases) “restored” so aggressively as to spoil the original treasures. Allied bombing in 1943 struck the on-site museum and severely damaged several houses. Following World War II, the Italian government launched widespread excavations to create jobs for the unemployed. A severe earthquake in 1980 further weakened the ancient city’s structures. Funding for preservation — though not necessarily for excavation — was often in short supply.

In 2008, the Italian government declared a yearlong state of emergency for Pompeii. A special commissioner was appointed to oversee improvements, but he was later accused of corruption, overspending and even damaging parts of the site. In November 2010 the Schola Armaturarum, or House of the Gladiators, partially collapsed following heavy rains, triggering negative headlines across Europe and beyond. Unesco, which had added the ancient city to its list of World Heritage sites in 1997, sent a team to assess the situation. The resulting report warned that “a considerable number” of other buildings were also at risk.

The negative attention finally triggered an influx of financing. In March 2012, the European Commission approved funding, with the goal of securing the ancient city as an enduring attraction in the region. When combined with money from the Italian government, the funds came to 105 million euros (about $116 million). The following month, “The Great Pompeii Project” was launched.

A new era

One of the first items on the agenda was to protect what had already been excavated. (Today, one third of the site remains underground.) Workers stabilized stone walls and buildings, restored frescoes, and installed new drainage systems to divert rainwater. They also affixed surveillance cameras throughout the ancient city to keep watch over Pompeii’s thousands of daily visitors.

The project has also led to archaeological discoveries: a treasure trove of amulets; a horse still wearing its bronze-plated saddle; a fresco of Narcissus staring at himself in a pool. A newly unearthed bit of charcoal graffiti has even shed light on the date of the famous disaster. Scientists now conclude that Vesuvius probably erupted on Oct. 24 — not Aug. 24, as long believed.

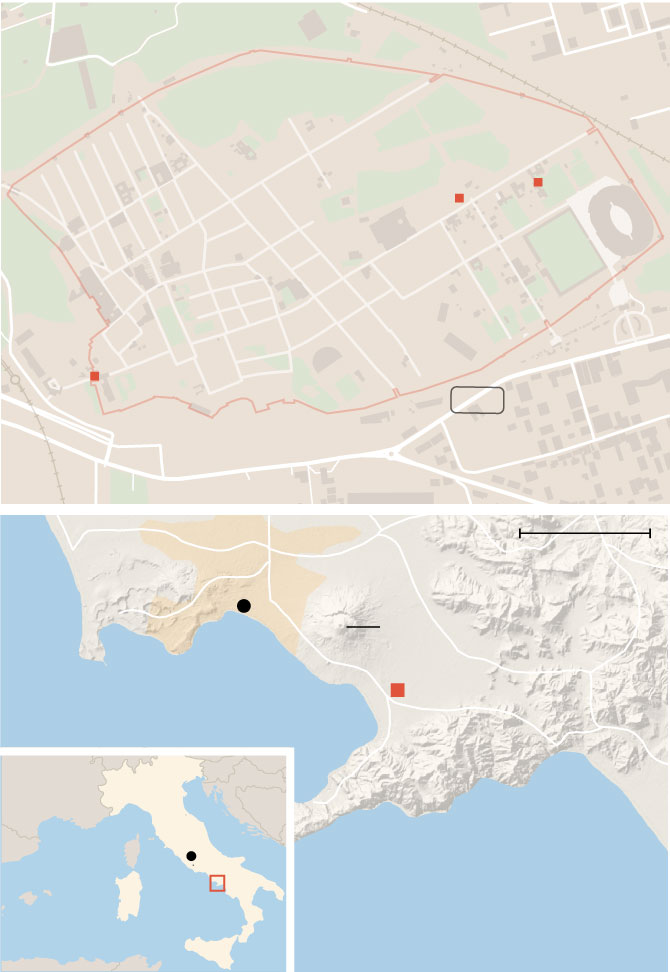

MOUNT

VESUVIUS

Via di Nola

Villa of

Julia Felix

Gulf of

Naples

Schola Armaturarum

Via della Fortuna

Via dell’Abbondanza

Amphitheatre

Via di Castricio

Via Stabiana

Gulf of

Salerno

Teatro

Grande

Porta Marina

Pompeii Scavi –

Villa Dei Misteri

station

Detail above

Via Plinio

Via di Nola

Villa of

Julia Felix

Schola

Armaturarum

Via della

Fortuna

Via dell’

Abbondanza

Amphitheatre

Via Stabiana

Via di

Castricio

Porta Marina

Teatro

Grande

Pompeii Scavi –

Villa Dei Misteri

station

Via Plinio

MOUNT

VESUVIUS

Gulf of

Naples

Gulf of

Salerno

Detail, right

All told, the project has allowed more than 130,000 square feet of the ancient city to be restored and opened (or reopened) to visitors, including the estate of Julia Felix and some three dozen other buildings. Sidewalks have been built along some of the major routes, opening up parts of the ancient city to people in wheelchairs or pushing strollers. The Antiquarium — a small, informative museum near Pompeii’s Porta Marina Gate — opened in 2016 after more than three decades of closure.

“Now we are out of the emergency,” Francesco Muscolino, an archaeologist with the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, said in his office on the edge of the ancient city. He added that the park became an autonomous entity a few years ago, which means that it can now keep all of the revenues from ticket sales (adult entry costs 15 euros, roughly $16.50). In the past, Dr. Muscolino said, that income went directly to Italy’s Ministry of Economy and Finance, which would then pay back a portion of the revenue to the park.

Challenges remain

Not everyone is as confident as Dr. Muscolino. Antonio Irlando, an architect and the director of the Osservatorio Patrimonio Culturale, a cultural heritage watchdog group, says that revenue from ticket sales must be supported by additional funds from the government. The conservation of Pompeii is “a duty that the government of Italy has to every Italian and to the whole world,” he said, adding that “a few years of lots of money is not enough to save Pompeii.” The focus, he stressed, must be on continual, painstaking maintenance.

One problem, Mr. Irlando claims, is that there are not enough guards to watch out for misbehavior among tourists. “Not everyone remembers that the excavations are an archaeological monument and not an amusement park,” Mr. Irlando said.

Managing tourist behavior has always been a challenge in Pompeii, an archaeological site that spans an area larger than 120 American football fields. And now tourist numbers are higher than ever. In 2009, nearly 2.1 million people visited. By 2018, that figure had risen to more than 3.6 million, an increase of more than 70 percent. This year, the number will be even higher. Nearly 450,000 people visited Pompeii in July, marking the highest monthly figure ever recorded.

And the behavior of visitors to the ancient city has long been troublesome. A small exhibition in the Antiquarium showcases stolen objects that visitors have sent back to Pompeii, claiming that the tiles, stones or figurines brought them bad luck. The new video cameras have improved surveillance, but the site is so big that plenty of areas remain unwatched.

“It is a risk. I’m glad that one third of the city is still buried,” said Glauco Messina, a licensed tour guide who added that he has seen visitors jumping barriers, picking up illicit mementos, touching frescoes, setting up tripods on fragile stone walls, and using flash photography, which can damage ancient paint. The situation isn’t helped by tourist companies that run unauthorized tours, often led by guides with uncertain qualifications.

“We’ve denounced them I don’t know how many times, but they’re still there,” Mr. Messina said of the unauthorized guides, who often lead very large groups and continue to operate in the park despite an official ban. Mr. Messina and other licensed guides — who must pass rigorous exams to earn their official “Guida Turistica” badges — warned that tourists should be wary of anyone who approaches them on the street outside the park. Tours with licensed guides can be booked inside Pompeii’s Porta Marina and Piazza Esedra entrances; official audio guides are also available inside the Porta Marina gate. Information can be found at pompeiisites.org/en/visiting-info.

Finding a balance

The number of visitors presents a challenge, but doesn’t necessarily pose a threat to the ancient city, says Stefano De Caro, the former director-general of the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property; Dr. De Caro also served as Pompeii’s director of excavations in the 1980s and is now on the park’s advisory board. After all, Dr. De Caro said in a recent interview, Pompeii used to be home to thousands of people; it has plenty of space for humanity. But if tourists are allowed to concentrate in the few most famous parts of the ancient city, then they could cause damage. The goal, he added, should be to better regulate the movement of tourists through the site.

“If visitors are free to circulate as they want, you need hundreds and hundreds of guards,” Dr. De Caro said, adding that even if Pompeii earns a good income from ticket sales, the revenue would not be enough to cover the high cost of such a service. (At the moment, about 160 guards work in the Archaeological Park of Pompeii; most are employed by Italy’s Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism, while just over 50 are funded by the park itself.) One approach could be to introduce guide-led themed itineraries, which would help to distribute tourists across the site, Dr. De Caro suggested. Additional services could also be added to the park’s less-frequented gates, to minimize crowding at the popular Porta Marina and Piazza Esedra entrances.

But regulating tourist movement will not be easy, Dr. De Caro added, noting that switching to a more structured system would generate opposition from transport providers and tour companies, not to mention tourists.

For visitors such as Sherry Pressman of Pembroke Pines, Fla., who visited Pompeii with her husband in August, the experience of walking through the ancient city was even better than she had expected. “I think it’s wonderful,” she said, “but it does need some more repair.”

The tourist experience will be critical to Pompeii’s future, perhaps just as much as excavations have been the defining feature of the site’s recent past. The goal must be to strike a balance between tourism and preservation, says Mary Beard, a professor of classics at Cambridge University and the author of an award-winning book on Pompeii.

“At one extreme, we have the nightmare scenario of the site being wrapped in cotton wool and accessible only to the privileged,” Professor Beard wrote in an email. “At the other we have the nightmare scenario of the site being flooded with visitors, clambering over the walls and ripping bits of mosaic from the floor. Our job is the find the right point in between.”