Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Friday pushed back against the idea that the monkeypox virus can spread through the air, saying the virus is usually transmitted through direct physical contact with sores or contaminated materials from a patient.

The virus may also be transmitted by respiratory droplets expelled by an infected patient who comes into physical contact with another person, they said. But it cannot linger in the air over long distances.

Experts on airborne transmission of viruses did not disagree, but some said the agency had not fully considered the possibility that respiratory droplets, large or small, could be inhaled at a shorter distance from a patient.

The World Health Organization and several experts have said that while “short-range” airborne transmission of monkeypox appears to be uncommon, it is possible and warrants precautions. Britain also includes monkeypox on its list of “high-consequence infectious diseases” that can spread through the air.

“Airborne transmission may not be the dominant route of transmission nor very efficient, but it could still occur,” said Linsey Marr, an expert on airborne viruses at Virginia Tech.

“I think the W.H.O. has it right, and the C.D.C.’s message is misleading,” she added.

In the United States, the monkeypox outbreak has swelled to 45 cases in 15 states and the District of Columbia, C.D.C. officials said at a news conference. The global tally has risen swiftly since May 13, when the first case was reported, to more than 1,450. At least 1,500 cases are still under investigation.

Historically, people with monkeypox have reported flulike symptoms before a characteristic rash appears. But some patients in the current outbreak have developed the rash first, and some have not had these symptoms at all, Dr. Rochelle Walensky, the agency’s director, said on Friday.

No deaths have yet been recorded in the current outbreak, she said.

Questions about airborne transmission of the monkeypox virus are important because the answers in turn will bear on recommendations for masking, ventilation and other protective measures should the outbreak continue to grow.

The C.D.C. said on Thursday that monkeypox “is not known to linger in the air and is not transmitted during short periods of shared airspace.” The statement followed a New York Times article on Tuesday in which scientists described uncertainties about transmission of the virus.

“What we do know is that those diagnosed with monkeypox in this current outbreak described close, sustained physical contact with other people who were infected with the virus,” Dr. Walensky said on Friday. “This is consistent with what we’ve seen in prior outbreaks and what we know from decades of studying this virus and closely related viruses.”

But monkeypox is poorly studied, other experts said, and occasional episodes of airborne transmission have been reported for the closely related smallpox virus. In a 2017 outbreak of monkeypox in Nigeria, infections occurred in two health care workers who had no direct contact with patients, scientists said at a recent W.H.O. conference.

A few patients in the current outbreak do not when or how they contracted the virus, C.D.C. officials acknowledged.

The agency is right to reassure the public that the outbreak is not a threat to most people, because monkeypox is not nearly as contagious as the coronavirus, said Dr. Donald Milton, an expert on airborne virus transmission at the University of Maryland.

Airborne transmission is unlikely to be a risk for anyone other than immediate caregivers, Dr. Milton said, but cautioned that denying the possibility entirely “is the wrong way to do it.”

When a virus is present in saliva or in the respiratory tract, as monkeypox has been shown to be, it can be expelled in respiratory droplets when talking, singing, coughing or sneezing, Dr. Milton and other experts said.

The droplets may be heavy and quickly fall onto objects or people, or they may be small and light, lingering in the air for long periods and distances. The C.D.C.’s assessment hinges in part on whether the virus is present only in large droplets or also in the very small ones, called aerosols.

A similar debate unfolded at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, when the agency and the W.H.O. focused on large droplets as the main route of transmission. But aerosols turned out to be a major driver.

The new C.D.C. guidance on monkeypox described the respiratory droplets emitted by patients as “secretions that drop out of the air quickly.”

But the virus “can be present in respiratory particles of any size,” not just large droplets, said Lidia Morawska, an air quality expert at Queensland University of Technology in Australia.

“In my view, there is no basis to the statement that the virus is transmitted only by large droplets and presenting infection risk only on close distances,” she wrote in an email.

Patients in the current outbreak seem to have become infected through close, sustained contact, C.D.C. officials said on Friday. But this can be difficult to determine.

What to Know About the Monkeypox Virus

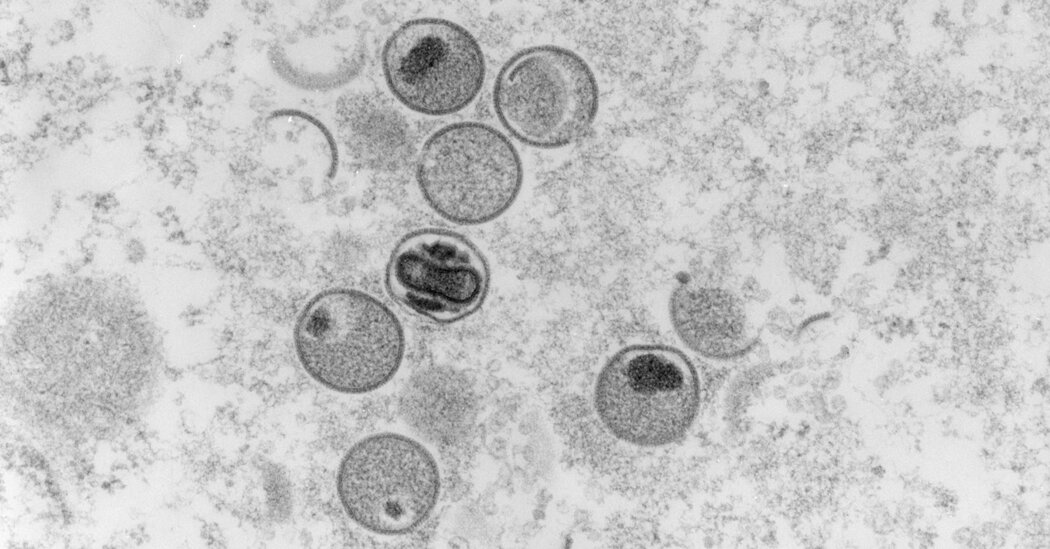

What is monkeypox? Monkeypox is a virus endemic in parts of Central and West Africa. It is similar to smallpox, but less severe. It was discovered in 1958, after outbreaks occurred in monkeys kept for research, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

When people are in close contact, it can be impossible to distinguish whether a virus was transmitted by touch, spray of large droplets or inhalation of aerosols, Dr. Marr said.

“The occurrence of transmission in such situations does not define how the virus got from one person to another,” she added. If transmission can occur by the spray of respiratory droplets, “then it almost surely occurs by inhalation of aerosols, too.”

Still, most experts agree that whatever the contribution of inhaled aerosols, monkeypox does not seem to be transmitted over the distances that the coronavirus or the measles virus can be.

“I agree that most monkeypox transmission occurs by touch — most likely direct touch between mucous membranes,” Dr. Milton said.

But the “C.D.C. seems to be stuck on the old terminology,” he said. “We really need to talk about transmission using terms that clearly say how it happens — through touch, spray or inhalation.”

The C.D.C. itself acknowledges the possibility of short-range airborne transmission in its advice to clinicians. The agency recommends that patients wear masks and that health care personnel caring for them wear N95 respirators, which are needed to filter out aerosols.

It also cautions that “procedures likely to spread oral secretions should be performed in an airborne infection isolation room.”

There is evidence that monkeypox can survive in aerosols and that inhaled virus can cause disease in monkeys. Airborne transmission may not be ideal for the monkeypox virus, however.

Patients may not release much virus in aerosols, the virus may not remain infectious for long, or the amount of inhaled virus needed to infect someone might be too high, Dr. Marr said.

If that’s the case, airborne transmission is likely to occur only among people who are close for long periods. Still, health officials in Britain, like those in the United States, have said that many patients do not seem to know when or where they might have become infected.

If they were infected without close contact, “it’s possible that airborne transmission has been occurring more than we realize,” Dr. Marr said.