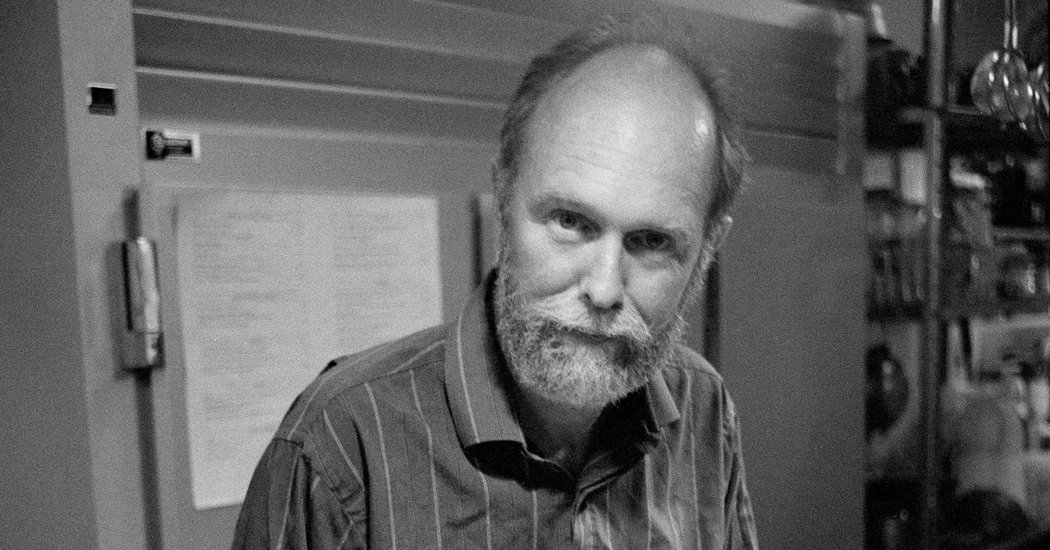

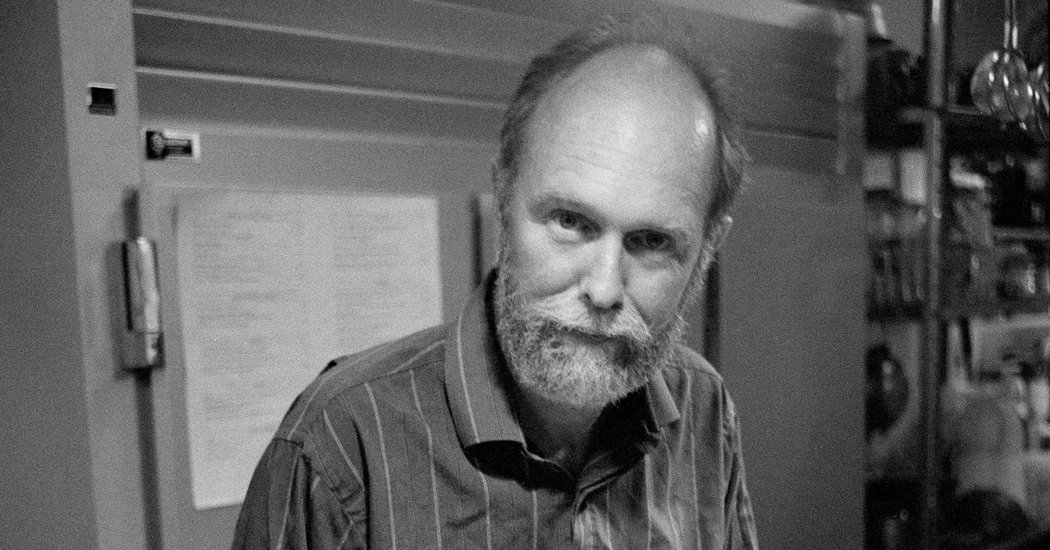

Bruce LeFavour, an eclectic, self-taught American cook who, on nothing more than three years in Europe and an innate appreciation of perfect ingredients, helped craft the early California cuisine movement, died on Oct. 4 at his home in Port Townsend, Wash. He was 84.

His death was confirmed by his daughter Cree LeFavour, who said his health had been declining since he had a stroke in 2015.

Mr. LeFavour (pronounced Le-FAVE-er), whose education in French food began in the late 1950s when he left Dartmouth for the Army and was stationed in France, would go on to open three restaurants across the United States. His first, in 1965, was in Aspen, where he developed a version of nouvelle cuisine before either the cooking style or the ski town had caught on among the nation’s elite.

He opened his last in Northern California in 1981 during a decade that saw Wolfgang Puck, Mark Peel and a host of other chefs refine the notion of a thoughtful but casual culinary approach based on California’s pristine ingredients. It was a movement that Alice Waters began when she opened Chez Panisse in 1971.

Inventive over the stove and hyper alert to any visual flaws on his plates before they left the kitchen, Mr. LeFavour much preferred to be called cook, rather than chef.

All his restaurants were off the beaten track. And yet, as Marian Burros, the longtime food writer for The New York Times, wrote in 1986 of his Paragon restaurant in Aspen, “It was the best the town had to offer and would have been equally successful in New York or San Francisco.”

The Paragon, which he ran from 1965 to 1974, managed to be both a hippie haven for counterculture royalty — the gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson was a frequent patron — and a top-notch go-to classic for foodies.

“It is possible that the most imaginative menus in America per capita can be found in this little town 200 miles from Denver,” Craig Claiborne, the influential restaurant critic for The Times, wrote during a visit to Aspen in 1969.

With its French-inspired menu, French waiters and French wines aging in its cellar, the Paragon was at the top of Mr. Claiborne’s list. For dinner, he started with a delicately seasoned quiche Lorraine. He then attacked the wild boar, expertly cooked with crisp skin, “the flesh tasting much like tender roast pork.”

Despite rave reviews, Mr. LeFavour kept his restaurants only as long as they held his interest.

As Aspen grew, he became restless and moved his family to central Idaho, where he opened a restaurant at the storied Robinson Bar Ranch, north of Sun Valley.

There he raised chickens, rabbits, ducks, pigs, and sheep, grew his own vegetables, made his own butter and cooked his own version of French cuisine.

“He was spoiled by the freshness and quality of the ingredients at the ranch,” his daughter Cree said. “We had eggs that had been under the hen two minutes before.”

That was good training for his next move, to the Napa Valley, where his restaurant, Rose et LeFavour, was an early adopter in California’s nascent farm-to-table movement.

He supported local farmers, who in turn grew what he asked for. He would bring them seeds that yielded unusual varieties of carrots and beans. A neighbor, a retired Chicago detective whom he referred to only as Mrs. Herb, raised snails for him.

When local farmers began growing arugula in the early 1980s, they had no idea how much to charge for it. The well-traveled Mr. LeFavour told them that in Europe, it cost the same as a pack of cigarettes. The farmers then pegged their arugula prices to the cost of Mr. LeFavour’s Lucky Strikes.

Three days a week, he drove an hour to Berkeley to buy fish at the Monterey Fish Market and dreamed up his menus on the drive back.

“He always said, ‘Shop first and see what’s available,’” his daughter recalled, “‘then plan your menu second.’”

Bruce LeFavour was born on Oct. 25, 1934, in Amsterdam, N.Y. His father, William Bruce LeFavour, was publisher of The Amsterdam Evening Recorder, which had been in his family for generations.

His mother, Harriett (Walden) LeFavour, a homemaker, died when Bruce was 11. He later attended boarding school at Phillips Academy Andover, where, he often said, he received an excellent education and learned to think critically. He graduated in 1953 and headed to Dartmouth.

In the summer of 1955, he joined a 900-mile canoe expedition across the harsh Barren Lands of Arctic Canada with five other young men. Known as the Moffatt expedition, after their leader, Arthur Moffatt, it became a notorious example of bad planning as they squandered their time, ran low on provisions, capsized in frigid waters and lost Mr. Moffatt to hypothermia. The others were lucky to survive.

Various accounts have been written of the harrowing journey. Mr. LeFavour wrote his as a novel, but it was never published.

He returned to Dartmouth, then dropped out before his scheduled graduation in 1957 and enlisted in the Army. After Army Language School, he worked as a counterintelligence officer in France, where he said he began his real education.

In 1961, after leaving the Army, he flew to Aspen for a friend’s wedding and planned to return to France but was awed by the mountains and stayed. He married Patricia Saaf in 1963 and they had two daughters.

With no visible means of support, they decided to open the Paragon, though they had no restaurant experience.

“Though patrons did not realize it at the time,” Ms. Burros wrote, “Mr. LeFavour was cooking a personalized version of what became nouvelle cuisine.”

He carried that tradition to Idaho. But soon he was itching to move to California, while his wife wanted to stay. They sold their ranch to the singer-songwriter Carole King and were divorced soon after.

He settled in St. Helena, 65 miles north of San Francisco, in the heart of Napa wine country. He and Carolyn Rose, his partner, opened Rose et LeFavour.

There, Mr. LeFavour refined his French influences by cooking with locally sourced raw ingredients.

“That was the start of the California cuisine movement,” said Joyce Goldstein, an author and chef who owned Square One, a restaurant in San Francisco.

He also was among the first to incorporate Asian elements into his dishes. He bought out Ms. Rose in 1986, then shuttered the restaurant the next year.

In 1990 he married Faith Echtermeyer, a photographer, with whom he traveled extensively. They hiked the French trail system and in 1999 collaborated on a book “France on Foot.”

She survives him. Besides his daughter Cree, he is also survived by another daughter, Nicole LeFavour; a sister, Sidney LeFavour; and two grandchildren.

Ms. Goldstein remembered him as an unpretentious man who loved working in the kitchen.

“He wasn’t out to get written up in magazines,” she said. “He was not a glory boy. He was a cook. To me, the highest compliment you can give a chef is to say he was a good cook.”