Earlier this month, Meharry Medical College, a 143-year-old historically black institution in Tennessee, proudly announced that it had received the second-largest grant in its history — $7.5 million to start a center to study public health issues that affect African-Americans.

But the gift has prompted a vehement backlash from African-American health experts and activists because of the source of the funds: Juul Labs, the fast-growing e-cigarette company, now partially owned by the tobacco giant Altria.

Black people in the United States have a higher death rate from tobacco-related illnesses than other racial and ethnic groups. Research into the health effects of tobacco products, including newer nicotine delivery systems like Juul’s popular vaping devices, was to be the first order of study for the new center.

The announcement set off several days of frantic phone calls and meetings among black public health leaders, who remember the tobacco industry’s history of targeting black communities with menthol cigarettes — and who don’t want black youths becoming addicted to nicotine through vaping.

“Juul doesn’t have African-Americans’ best interests in mind,” said LaTroya Hester, a spokeswoman for the National African American Tobacco Prevention Network, which is sending a letter of protest to Meharry. “The truth is that Juul is a tobacco product, not much unlike its demon predecessors.”

Over the past year, Juul has hired numerous leaders with close ties to the black community as consultants and lobbyists. Among them are Benjamin Jealous, the former head of the N.A.A.C.P.; Heather Foster, a former adviser to President Obama who served as his liaison to civil rights leadership; and Chaka Burgess, co-managing partner of the Empire Consulting Group, who serves on the governing boards of the N.A.A.C.P. Foundation and the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation and its political action committee.

Juul has contributed to the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation and to the National Newspaper Publishers Association, a trade group for African-American community newspapers.

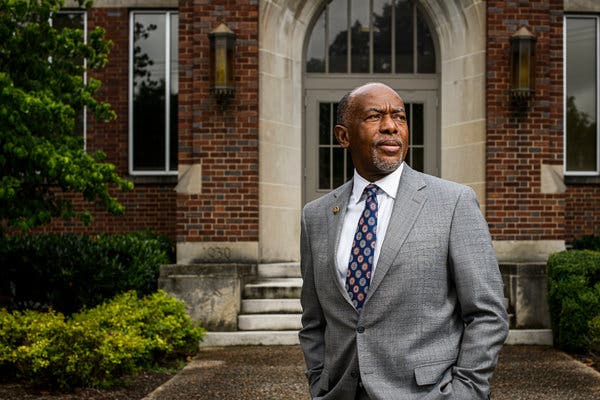

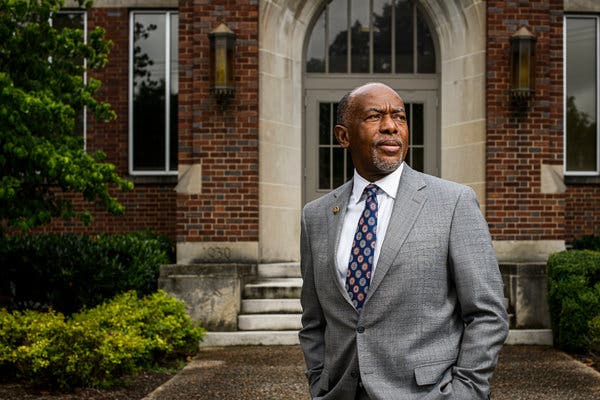

But Meharry officials stressed that they approached Juul, not the other way around. The college’s president, Dr. James E.K. Hildreth Sr., has said he was confident that the new center’s work would be free of Juul’s influence.

And, he said, research on nicotine and tobacco is of vital importance to the six million African-Americans who are smokers.

CreditWilliam DeShazer for The New York Times

“We have historically found ourselves occupying the last seat at the table when research is conducted on emerging public health issues that profoundly affect minority communities,” Dr. Hildreth wrote in a letter to the Meharry community. “We have paid a heavy price for being shut out.”

The debate highlights an ongoing, and heated, quandary in scientific research: Is it possible to take so much corporate money and not become biased in the funder’s favor?

Lindsay Andrews, a spokeswoman for Juul, said the company had no specific conditions for the grant, which will be paid over five years.

“There are many questions about the overall public health impact of vapor products, and Juul products in particular, that a robust body of public health research must help answer,” Ms. Andrews said.

Meharry, founded in Nashville in 1876, is the nation’s largest medical research center at a historically black institution. Dr. Hildreth, a Rhodes scholar with a Ph.D. from Oxford and an M.D. from Johns Hopkins, became president of the university in 2015 and is determined to expand its research. To do so, he has been in discussion with technology companies, foundations and the federal government, in addition to Juul.

Last summer, Dr. Hildreth and Patrick Johnson, Meharry’s senior vice president for institutional advancement, met with Juul representatives in Washington to ask the company to help underwrite a research program which would study, among other things, e-cigarettes.

They were close to an agreement when Juul executives told them they were in talks with Altria to pay Juul nearly $13 billion for a 35 percent stake, a transaction that would give the e-cigarette maker access to Altria’s shelf space in stores and buttress its lobbying muscle.

Meharry, like many medical schools, has had a policy of turning down tobacco company donations. The disclosure led to considerable soul-searching among the administrators.

“We have an anti-tobacco stance, and one of the things that caused pause for everyone involved was Altria,” Mr. Johnson said. “The whole thing had to be re-examined with more detail.”

After months of discussion, Mr. Johnson said, Meharry agreed to accept the money.

“Altria is an investor in this device company,” he said. “They don’t have a voice or say-so. To this date, as we stand here, Juul does not sell tobacco products. As long as that remains, we are comfortable with the decision that we came to.”

Dr. Hildreth said the new program, to be called the Meharry Center for the Study of Social Determinants of Health, will conduct research into health conditions and issues related to tobacco and nicotine-delivery products, including e-cigarettes.

The center will later study the impact of alcohol use and food instability on underserved communities, among other issues.

Juul will not suggest studies, Mr. Johnson said, nor have any input before publication. The center will also convene annual meetings on tobacco and nicotine-delivery products, and develop public education campaigns.

But many public health groups said independence from Juul will be impossible.

“That’s a fantasy,” said Sharon Y. Eubanks, who was lead counsel for the United States in the landmark lawsuit in which the tobacco industry was found in 2006 to have conspired for decades to hide the dangers of smoking.

Ms. Eubanks, who is an advisory board member of the Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education at the University of California, San Francisco, is particularly troubled by the industry’s record of promoting menthol cigarettes in black neighborhoods. These brands are especially addictive because the menthol flavor masks the cigarette’s harshness.

Altria’s best-selling Marlboro cigarette brand comes in menthol and regular tobacco flavors, as do Benson & Hedges and other cigarettes. Juul has refused to stop selling menthol flavor pods in stores, though it has agreed to discontinue selling most of its other flavors, except online.

According to the N.A.A.C.P.’s Youth Against Menthol campaign, about 85 percent of African-American smokers aged 12 and older smoke menthol cigarettes, compared with 29 percent of white smokers.

“Juul is cozying up to the black community, and that makes it harder for some parts of the black community to call them out on their targeting of African-Americans,” Ms. Eubanks said.

Hilary O. Shelton, director of the N.A.A.C.P.’s Washington bureau, said he is glad that Meharry took the money.

Mr. Shelton said he had spoken with Juul and that he believed the company sincerely wants to sell its products to adult smokers as an alternative to cigarettes. Beyond that, he said, he is confident in Meharry’s integrity.

“It really is an issue of whether we trust in the integrity of the institution to do this very important research,” said Mr. Shelton. “I can’t think of anyone I’d trust more than Meharry.”

Juul is under investigation by the Food and Drug Administration and at least two state attorneys general for alleged marketing to youths. The company also has struggled to give away some of the money earned from its 70 percent share of the United States vaping market.

Researchers at Yale University, Boston University, Stanford University, Johns Hopkins and the University of Louisville, among others across the country, have shunned Juul’s grant offers.

Those rejections have presented a problem for Juul, which needs strong science to prove that “juuling” offers more public health benefit than risk. The company now has until 2022 to submit that evidence — and the deadline might be moved up, pending the outcome of a case in federal court.

Dr. Ross McKinney Jr., chief science officer at the Association of American Medical Colleges and a longtime bioethicist, studies the impact of donations on research.

“What do you do with money from a source that is in some way contaminated?” he said. “Tobacco has a specific history of hiring scientists to confuse the overall picture so that policies that might be restrictive would not go forward.”

But, he added, there are questions about Juul that need answers and for which independent funding might be very difficult to get.

“If they do it right, in terms of studying who and how people become addicted, you could make a judgment that it is worth taking the money,” he said.

In a newspaper editorial last week, Dr. Hildreth said his eyes were wide open. The tobacco industry, he said, “has taken our money and delivered sickness and death in return. We at Meharry intend to advance the fight for better health and longer life by turning that insidious relationship on its head.”