Antwaun Sargent adapted this essay from his new book, “The New Black Vanguard: Photography Between Art and Fashion,” to be published next month by Aperture.

In 2018, American Vogue published two covers featuring the global icon Beyoncé on its esteemed September issue. Though it was her fourth time fronting the venerable monthly, this was the shoot heard around the world: For the first time in the magazine’s century-long history a black photographer, Tyler Mitchell, had been commissioned to create its covers.

On one cover the musician is conveying a temporal softness and an air of modern domesticity in a white ruffled Gucci dress and Rebel Rebel floral headdress; on the other cover she is standing amid nature, wearing a tiered Alexander McQueen dress with Pan-African colors, her hair braided into cornrows. Her gaze is confident, a symbol of black motherhood, beauty and pride.

“To convey black beauty is an act of justice,” says Mr. Mitchell, who was just 23 years old when the photographs were published.

For Mr. Mitchell, the Beyoncé portraits, one of which was recently acquired by the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, are suggestive of his broader concern to create photography that contains “a certain autobiographical element.” Mr. Mitchell, now 25, grew up in Atlanta and was fascinated by art and fashion images he saw on Tumblr. “Fashion was always something distant for me,” he says.

His own images evoke what he calls a “black utopia” — a telegraphing of black humanity long unseen in the public imagination. In “Untitled (Twins II)” from 2017, he features the brothers (and fashion models) Torey and Khorey McDonald of Brooklyn, seen draped in pearls and resting against a pink and cream backdrop. The photographs document the style, identity and beauty of black youth — “what I see to be a full range of expression possible for a black man in the future,” he explains. His subjects are often at play in grass, smiling in repose and occasionally peer with an honest gaze at the camera.

Mr. Mitchell is a part of a burgeoning new vanguard of young black photographers, including Daniel Obasi, Adrienne Raquel, Micaiah Carter, Nadine Ijewere, Renell Medrano and Dana Scruggs, who are working to widen the representation of black lives around the world — indeed, to expand the view of blackness in all its diversity. In the process, they are challenging a contemporary culture that still relies on insidious stereotypes in its depictions of black life.

These artists’ vibrant portraits and conceptual images fuse the genres of art and fashion photography in ways that break down their long established boundaries. They are widely consumed in traditional lifestyle magazines, ad campaigns, museums. But because of the history of exclusion of black works from mainstream fashion pages and the walls of galleries, these artists are also curating their own exhibitions, conceptualizing their own zines and internet sites, and using their social media platforms to engage directly with their growing audiences, who often comment on how their photographs powerfully mirror their own lives.

In 2015, the South African photographer Jamal Nxedlana, 34, co-founded Bubblegum Club, a publishing platform with a mission to bring together marginalized and disparate voices in South Africa, and to “help build the self-belief of talented minds out there in music, art, and fashion.” Mr. Nxedlana’s Afrosurrealist images illustrate the stories of young artists from across the African diaspora. He sees his work as a form of visual activism seeking to challenge the “idea that blackness is homogeneous.”

It’s a perspective often seen in the work of this loose movement of emerging talents who are creating photography in vastly different contexts — New York and Johannesburg, Lagos and London. The results — often in collaboration with black stylists and fashion designers — present new perspectives on the medium of photography and notions of race and beauty, gender and power.

Their activity builds on the long history of black photographic portraiture that dates to the advent of the medium in the mid-1800s. More immediately, their images allude to the ideas of self-presentation captured by predecessors like Kwame Brathwaite, Carrie Mae Weems and Mickalene Thomas. What is unfolding is a contemporary rethinking of the possibilities of black representation by artists who illustrate their own desires and control their own images. In the space of both fashion and art, they are fighting photography with photography.

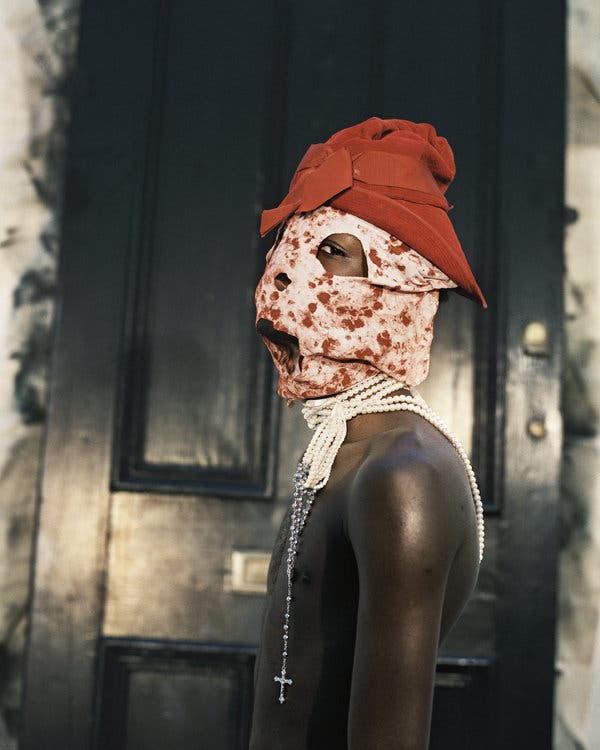

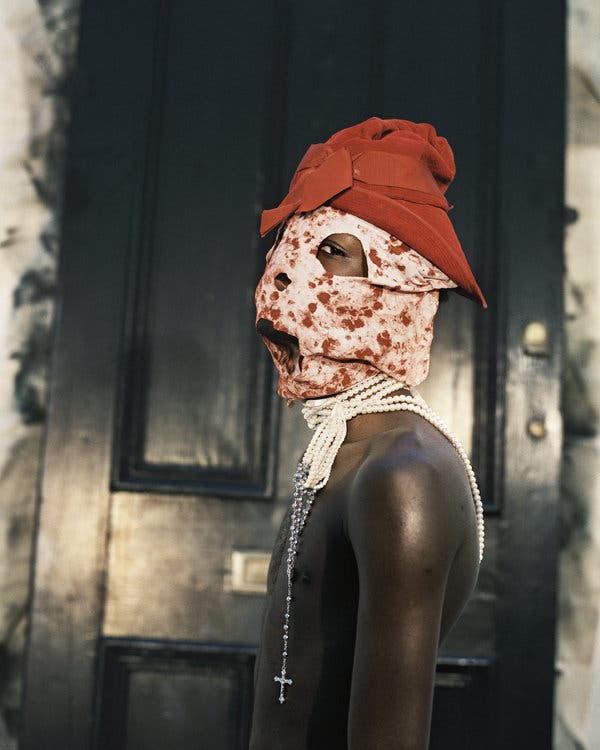

“The fashion image is vital in visualizing minorities in different scenarios than those seen before in history,” notes Campbell Addy, 26, a British-Ghanian photographer. Mr. Addy’s emerging archive gives pride of place to more fluid expressions of sexuality and masculinity in stylized images — like his untitled portrait of a shirtless black man whose face is covered in a makeshift red-and-white mask and his neck adorned with pearls and a rosary. “To play with fashion is to play with one’s representation in the world,” adds Mr. Addy, who also founded a modeling agency and the Niijournal, which documents religion, poetry, fashion and trends in photojournalism. “There’s a sense of educating the viewer,” he says.

Inspiration for Arielle Bobb-Willis’s pictures of black figures, whose faces are generally obscured from the camera’s gaze and whose bodies are captured in unnatural poses, can be found in the vivid canvases of modernist African-American painters such as Jacob Lawrence and Benny Andrews.

MS. Bobb-Willis is interested in how these artists applied a sly sense of abstraction in their portraiture, pushing representation beyond realism and stereotype. In her works, such as “New Orleans” (2018), a picture of a female figure wearing candy-colored garments as her body bends every which way before an abandoned storefront, Ms. Bobb-Willis, 24, showcases what she calls the personal “tension” of wanting to be visible in a culture that has long misrepresented the realities of black people.

For Quil Lemons, notions of family are a central concern. Mr. Lemons, 22, says his “Purple” (2018) series, striking portraits of his grandmother, mother, and sisters in his hometown Philadelphia, draw on a black-and-white photograph of his grandmother in a frontier-style dress. The four generations of women in his photos wear Batsheva floral print dresses that he selected to express a sense of home and intimacy. “The images are advocating, illuminating and cementing others’ existence,” says Mr. Lemons. “Overall, I’m offering insight or a glimpse into a world or life that could be overlooked.”

The British-Nigerian photographer Ruth Ossai, 28, also incorporates her own Ibo family in eastern Nigeria and relatives in Yorkshire, England. “I try to show texture, depth and love — the strength, tenacity and ingenuity of my subjects,” she explains. In Ms. Ossai’s elaborate, playful and fashionable portraits, they are dressed in a mix of traditional garments and western wear. She says of her photographs, “Young or old, my aunties and uncles flaunt our culture and sense of identity unapologetically, with a sense of pride and confidence.”

Her 2017 series, “fine boy no pimple” features her younger cousin, Kingsley Ossai, reclining in an oversized red suit and yellow durag while holding an umbrella, against a printed backdrop depicting a pastoral landscape. Much of her work, which sometimes incorporates collage and has been published in fashion campaigns for Nike and Kenzo, is inspired by contemporary West African pop music, Nollywood films and the pomp of Nigerian funerals. It is evocative of the African mise-en-scène studio portraiture of the 1960s, created by such artists as Sanlé Sory in Burkina Faso and Malick Sidibé in Mali.

The documentary nature of Stephen Tayo’s street snapshots of stylish shopkeepers, elders and youth in Lagos speak to this generation’s interest in recording contemporary black identity and its use of photographs as a space for fresh invention. His untitled 2019 group shot of modish young men huddled together on a street in colorful suiting showcases traditional Nigerian weaving techniques while alluding to the “youthquake” movement taking hold in his city. The image also conjures the post-independence street photography of the Ghanaian artist James Barnor.

“The current generation is keen on just believing in their crafts” says Mr. Tayo, 25, whose work is currently on view in “City Prince/sses” at Palais de Tokyo in Paris. “It’s also very to be part of a generation that is doing so much to regain what could be termed ‘freedom.’”

Images of the black body are not the only way these photographers consider notions of identity and heritage. The Swiss-Guinean photographerNamsa Leuba focuses on specific objects used in tribal rituals across the African diaspora to probe, conceptually, the way blackness has been defined in the western imagination. Ms. Leuba, 36, creates what she calls “documentary fictions” that possess an anthropological quality. In series like “The African Queens” (2012) and “Cocktail” (2011), her figures are draped in ceremonial costume and surrounded by statues imbued with nobility.

Awol Erizku, in addition to his celebrity portraits of black actors and musicians such as Michael B. Jordan and Viola Davis, creates powerful still life imagery filled with found objects set against monochromatic backdrops. They reference art history, black music, culture and nature. The works also highlight Mr. Erizku’s interest in interrogating the history of photography while disrupting existing hierarchies.

In “Asiatic Lilies” (2017), a black hand with a gold bangle holds a broken Kodak Shirley Card, named for the white model whose skin tone was used to calibrate the standard for color film. The hand is comparing the card to objects that have been whitewashed, including a bust of Nefertiti, painted black. Mr. Erizku, 31, also includes in his photograph a small gold sculpture of King Tut, and fresh lilies, the flower of good fortune.

The message for his generation of image makers is clear: “I am trying to create a new vernacular — black art as universal.”