Bjorn Thorbjarnarson, a New York surgeon who famously treated the shah of Iran and Andy Warhol before becoming a central figure in a widely publicized lawsuit over Warhol’s death after surgery in 1987, died on Oct. 4 in Warren, N.J. He was 98.

The death, at a care facility, was confirmed by his daughter Lisa Enslow.

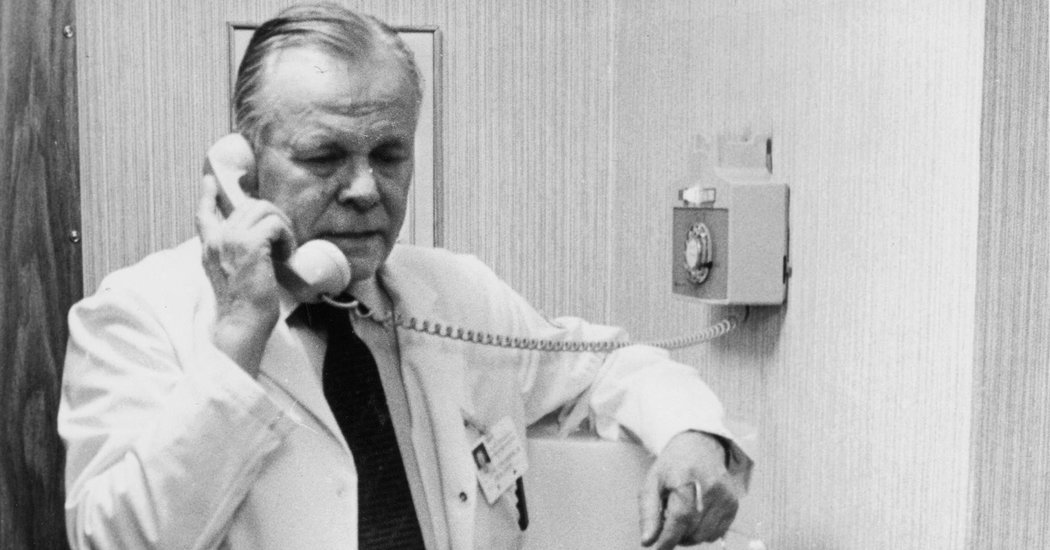

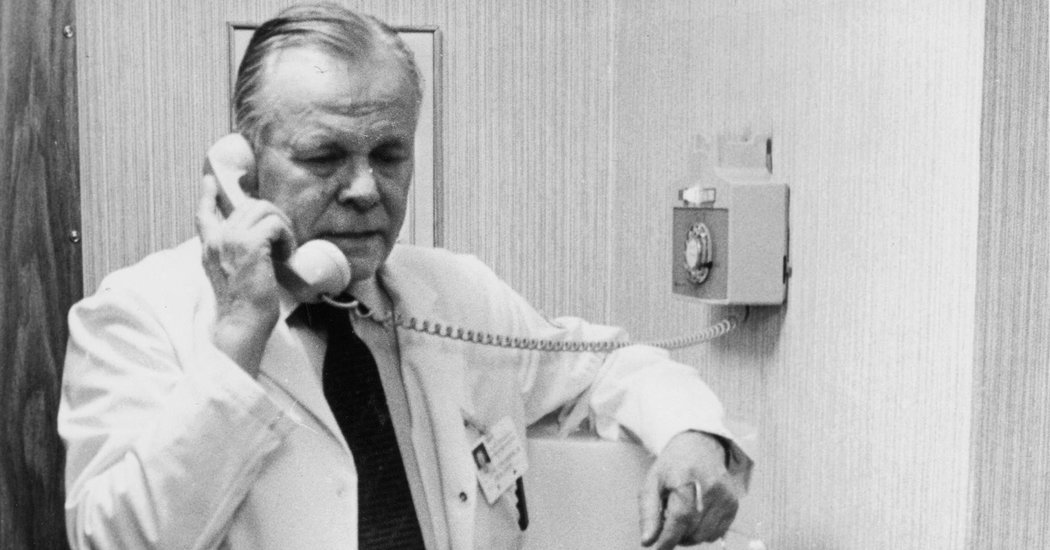

Dr. Thorbjarnarson was one of the foremost experts on surgeries of the biliary tract — involving the liver, gall bladder and bile ducts — when he was called to remove Warhol’s infected gallbladder in 1987 at New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center, where he worked for virtually his entire career. (Ms. Enslow said he had treated other famous patients as well, including Johnny Carson, the physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer and the artist Ellsworth Kelly.)

Dr. Thorbjarnarson (who pronounced his surname thor-bee-ON-a-son so that it would be easier for his American colleagues to master) completed the operation on Warhol without incident, and Warhol seemed stable as he recovered in a private hospital room. But his condition deteriorated overnight, and he died in the early hours of Feb. 22 at 58. At the time, many newspapers characterized the operation as “routine.”

That April, the New York State Health Department released a report concluding that Warhol’s treatment had been inadequate. The Manhattan district attorney’s office soon mounted an investigation, but it found insufficient evidence to bring criminal charges.

Warhol’s estate continued a private investigation, however, and in 1991 filed a wrongful-death lawsuit against the hospital (now known as NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center) and individuals involved in his care. At a trial in State Supreme Court in Manhattan that year, the estate’s lawyers argued that doctors and nurses had neglected Warhol’s postoperative care and given him an unsafe amount of intravenous fluids.

“We are saying that Warhol died from internal drowning,” Steven Hayes, a lawyer for the estate, told The New York Times in 1991.

Lawyers for the hospital, as well as for Dr. Thorbjarnarson and Dr. Denton S. Cox, the attending physician and Warhol’s longtime doctor, contended that Warhol had been well enough to watch television and make telephone calls from his hospital room as he recovered. An autopsy gave the cause of death as cardiac arrhythmia, which the hospital argued was related to Warhol’s poor health and not caused by medical error or negligence.

Glenn Dopf, the doctors’ lawyer, said in his opening statement at the trial that there was no evidence of fluid overload. “It’s bunk, baloney and a fantasy,” he said.

Dr. Cox said Warhol’s condition had been precarious when he entered the hospital. He said that he first diagnosed a gallstone in Warhol in 1973, but that Warhol had refused to undergo surgery because of a fear of hospitals that dated to 1968, when he was shot by the radical feminist Valerie Solanas.

The hospital settled with Warhol’s estate a few weeks after the trial began. Dr. Thorbjarnarson retired in 1989, and maintained to the end that the hospital’s treatment of Warhol had been proper.

Three decades after Warhol’s death, an investigation by Dr. John Ryan, a medical historian and retired surgeon, supported the hospital’s version of events.

“This was major, major surgery — not routine — in a very sick person,” Dr. Ryan told the art critic Blake Gopnik, the author of a forthcoming biography of Warhol, for a 2017 Times article about the Ryan investigation.

Dr. Ryan found that Warhol had a family history of gallbladder problems, had been badly ill for at least a month, and had been dehydrated and emaciated before he underwent surgery.

Dr. Thorbjarnarson said that Warhol was so terrified of the hospital that he pleaded with him to treat him at home, Mr. Gopnik wrote.

“Dr. Thorbjarnarson refused Warhol’s entreaties and found himself justified three days later, when the sick man was at last on the operating table,” Mr. Gopnik said, adding, “The surgeon found a gallbladder full of gangrene.”

Dr. Thorbjarnarson had earlier been in the news when Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the shah of Iran, journeyed to Manhattan for lymphatic cancer surgery in October 1979, months after he was deposed in the Iranian revolution.

Dr. Thorbjarnarson led a team of surgeons in removing the shah’s gallbladder, a portion of his liver and several gallstones blocking a bile duct — all under highly unusual circumstances.

“Armed guards controlled the traffic to the patient’s room, and all blinds were always down,” Dr. Thorbjarnarson wrote in a letter in response to “The Shah’s Spleen: Its Impact on History,” an article in The Journal of the American College of Surgeons, in 2010. “Threatening calls were received by nurses attending, but none to me. Outside, the hospital was surrounded by a howling mob, controlled by barricades, calling for the shah’s head.”

The shah survived the surgery and left New York after some weeks of recovery. But his condition worsened — his spleen was removed in Egypt near the end of March 1980 — and he died that July.

Bjorn Thorbjarnarson was born on July 9, 1921, the seventh of eight children of Thorbjorn Thordarson and Gudrun Palsdottir, in the village of Bildudalur in the remote Westfjords region of northwestern Iceland. His father was a doctor who visited distant patients on horseback; his mother was a homemaker.

Bjorn went to a boarding school in the city of Akureyri in northern Iceland, to which he traveled by fishing boat or on horseback, his family said. He graduated from the University of Iceland’s medical school in 1947, trained in the Icelandic countryside and then moved to New York.

He began working at New York Hospital in 1948, studying under Dr. Frank Glenn, a surgeon who treated the shah in the early 1950s. In the ’50s Dr. Thorbjarnarson served in the Navy for two years. In 1955 he married Margaret Brown, a nurse he had met at the hospital. She survives him.

In addition to his wife and his daughter Lisa, he is survived by three other daughters, Kathryn Thorbjarnarson and Kristin and Gudrun Bjornsdottir; 11 grandchildren; and 20 great-grandchildren. A son, Paul, died in 1996, and another son, John, a renowned expert on crocodilians, died in 2010.

Susan C. Beachy contributed research.