WASHINGTON — Three years after discovering that a military laboratory had shipped live anthrax to facilities around the world, the Department of Defense still has not developed a plan to evaluate its biological security practices, the federal Government Accountability Office reported on Thursday.

The department has implemented about half of the procedural changes that had been recommended, the G.A.O. said. But the Pentagon still has not established a way to measure the effectiveness of these reforms, making it difficult for experts to determine whether safety has improved.

“When it comes to reforming procedures, this is not a one-off thing that you can do once and take a vacation,” said Gigi Gronvall, a biosecurity expert at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

“We must be careful that the evaluations and procedures intended to increase safety actually do that,” she added.

A spokesman at the Department of Defense declined to comment.

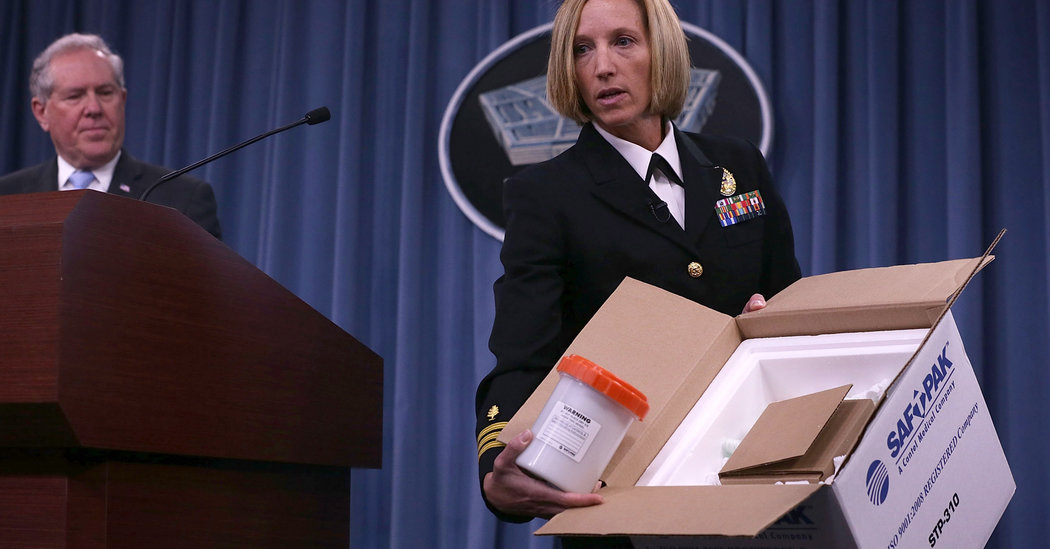

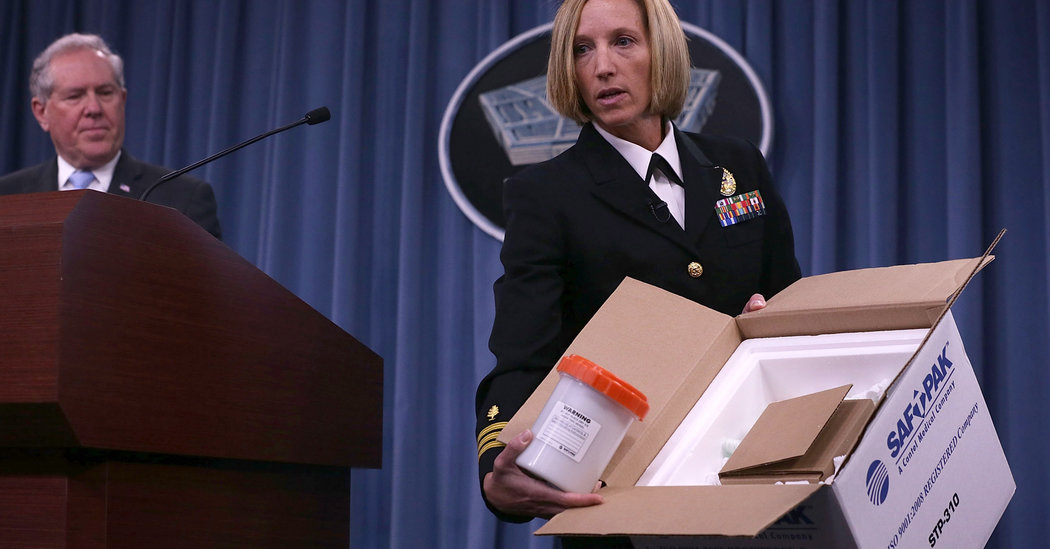

Concern over biosecurity at government labs flared in 2015 following the revelation that 575 shipments of live anthrax bacteria had been sent over the course of a decade from Dugway Proving Ground in Utah to 194 government and private labs in the United States and seven other countries.

An early review by the Pentagon blamed insufficient testing: Only about 5 percent of the samples that the lab irradiated were reviewed to ensure that anthrax actually had been inactivated. A more detailed investigation later that year found “a culture of complacency” among senior managers at Dugway.

Following the incident, the Army made 35 recommendations for improving safety at labs that handle dangerous agents. The G.A.O. assessment found that the department had implemented 18 of the changes and had “actions underway” to implement the remaining 17.

But the report found that the bio-risk program office, established in March 2016 to help oversee changes to safety protocols, had not established long-term goals, midterm objectives or even metrics to track improvement.

The G.A.O. also reported that it was not clear that lab specialists who test and evaluate biological agents remained independent from those who develop the agents and have an interest in seeing them approved.

The Department of Defense had acknowledged the issue, the report said, but had not addressed it.

The military also had failed to conduct a study of its infrastructure to determine whether facilities handling high-risk pathogens could be consolidated under a unified command for safety reasons.

Efforts to reform the government’s approach to biological security came on the heels of lab safety lapses at other agencies as well. Six vials of smallpox virus, discovered at a lab at the National Institutes of Health in 2014, were believed to have been stored there for 50 years. The samples were quickly destroyed.

Also in 2014, a lab at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention accidentally contaminated a relatively benign flu sample with a dangerous H5N1 bird flu strain. Together, the incidents led to temporary closings of anthrax and flu labs at the agency.

Follow Emily Baumgaertner on Twitter: @Emily_Baum