Propped with his style crew against the putty-tone headboard of a lumbering, half-made bed, Nay Campbell was in his element. The setting was a blandly furnished room in the once storied New Yorker Hotel on the edge of Hell’s Kitchen. An Art Deco monument that has seen better days, the hotel, with its pallid interiors and half-lit corridors, could have served as a backdrop for one of Andy Warhol’s louche, loosely rambling films.

On a recent Monday morning the hotel was the scene of a fashion shoot. Mr. Campbell’s oddly assorted elastic-limbed models, dancers and a publicist’s mother vamped in wispy negligee silks, taffeta minis and tailored gabardines that were evocative simultaneously of Russ Meyer’s big-screen bombshells and fragile Warhol waifs.

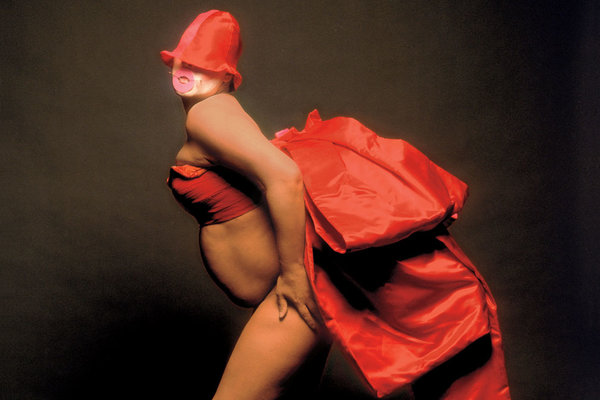

AE Andreas shows off a slashed varsity jacket by Claire Fleury. CreditDustin Pittman for The New York Times

There was a pale blue chiffon housecoat, an ostrich-bordered trench and a sweet gingham frock, demure from the front but plunging at the rear toward the model’s tailbone. Each item was part of Mr. Campbell’s spring 2019 Beyond the Valley collection, a line billed on his Lordele website as “bringing a queer feminine energy to New York’s fashion scene.”

Mr. Campbell, who is in his early 20s, is among the latest in a raft of designers deliberately and insistently invoking “queer,” a onetime slur that has been repurposed several times in recent decades and is now being reclaimed by younger members of the L.G.B.T.Q. community as a badge of defiance, of wily progressivism and willful flamboyance.

“The style is all about identity and unfettered self-expression,” said Rob Smith, the founder of the Phluid Project, an outpost of gender-neutral fashion in Lower Manhattan. “At the same time it’s a political statement, a symbol of resistance against a repressive government. It’s a way of stating, ‘I’m going to push back.’”

It can also be an unabashed marketing gambit.

Working in cramped studios, poised over cutting tables on the Lower East Side, unveiling collections in sprawling Chinatown lofts, Mr. Campbell and his design-world peers are striving, sometimes nakedly, to position themselves as fashion’s next new thing. Standard bearers of gender fluidity, they conceive their work as a vibrant and often risqué corrective to the flatness pervading New York runways of late.

They aspire to inclusivity, parading their work on models of mixed race, size, gender and age, competing to position themselves as successors to pioneering gender-fluid labels, including Telfar, Hood by Air, Luar and Gypsy Sport, that have made inroads into the mainstream.

“The designers at those houses are now kings of fashion, but once they were just kids on the Bowery,” Mr. Campbell said, referring to, among others, Rio Uribe of Gypsy Sport and Shayne Oliver of Hood by Air. “They proved that this is actually a market and not just this kind of editorial niche. People like me are the second wave of that.”

Aiming to counter fashion’s dearth of invention, they offer looks that are often raw by design, an aesthetic fusion of street and athletic wear, with distinct sadomasochistic undertones and, most recently, the over-the-top femininity of curve-clutching knits, layers of lace and filmy lingerie.

Little-known or emerging designers like Mr. Campbell, Scooter LaForge (an artist who creates hand-painted one-off designs for Patricia Field), and the Dutch-born Sophie Hardeman, admired for her kinky variations on denim, rarely sell in mainstream outlets. They remain closely watched just the same, wielding an impact that only a decade ago could not have been foreseen.

In 2015, James Michael Nichols, then of HuffPost Gay Voices (since renamed Queer Voices), defined how 14 queer, trans and queer-adjacent designers were changing mainstream fashion.

He looked at Bcalla, whose designer Brad Callahan was making suggestively slashed retro-futuristic looks; Tilly deWolfe and Tom Barranca of Tilly and William, whose elasticized frocks are conceived to fit a range of shapes and sizes; and Gogo Graham, who confects shimmering slip dresses and gowns for transgender women like herself.

Mr. LaForge, who favors a raw aesthetic, has roughed up Hermès bags and mail-order kilts with painted slogans and racy motifs that echo those of his artwork. His latest pieces, including a fluorescent ball gown appliquéd with miniature toy cars, graphic tape and workman’s gloves, resist mass production.

“I call it anti-fashion,” he said. “It’s not perfect.”

That unfinished look is a hallmark of a lot of queer collections, some pieced together from incongruous elements: a tailored jacket, say, with lace lapels; a sheer frock combined with bearlike fake fur slippers. Others are cobbled from castoff jerseys, salvaged silks and oddments of lace or organdy trim.

Ms. Hardeman strives for a relatable pastiche built on a kind of cut-and-paste technique. She tends to rework street-style staples: work wear with biker regalia, lacy undies with fatigues. She fashions her “prom jeans” from a mix of stiff denim and cascading panels of silk.

Once primarily a blend of street wear and club gear overlaid with B.D.S.M. fantasies, the queer aesthetic, if indeed there is one, is clearly showing a gentler side.

For too long, “masculine-leaning presentation” was “the single gold star standard of queer style,” Anita Dolce Vita, the founder and editor of dapperQ, a queer style magazine, argued in Them, Condé Nast’s L.G.B.T.Q.-oriented website. Now, she said, labels like Chromat and its queer-friendly kin “are reclaiming femininity from its second-class status.”

Claire Fleury whips up her collections from limited-run fabrics and rolls of trim to produce a mash-up of sports-influenced pieces and peignoir-ish cover-ups that are revisionist interpretations of conventional femininity. Ms. Fleury, who showed a pop-up collection at Phluid Project last month, is especially partial to extravagant womanly flourishes.

“If you say queer fashion, I see people dancing and wearing gorgeous unicorn colors, feathers and boas,” Ms. Fleury said. Her tartly sexy looks, like a varsity jacket slashed to ribbons and an airy frock with outsize holes and wafty boudoir sheers, are “just another way of being dressed and undressed at the same time,” she said.

The collection sold at Phluid Project betrayed the influence of gender-neutral runway influencers like Gucci and, more recently, Palomo Spain, both of which have made waves on occasion by showing shrilly colorful cocktail looks on men.

“I would like to see anybody wearing my clothes, and I do mean anybody,” Ms. Fleury said. “I don’t care if you’re a man or woman, black or white, 2 or 92, size 4 or 20.”

That sort of pitch for radical inclusiveness has resonated with fashion industry leaders and, not less, with younger consumers. Last year the Council of Fashion Designers of America added unisex and nonbinary as a category to be included in the New York Fashion Week calendar.

Back in 2016, market research showed changes in points of view on gender among Gen Z consumers, some 38 percent of whom said they “strongly agree” that “gender doesn’t define a person as much as it used to.”

That figure will be encouraging to the self-professed outliers who have embraced the word “queer” as a proclamation of empowerment and, perhaps less transparently, as a marketing tool to lend their work cachet.

Not news to Ms. Hardeman. Reappropriating the word “is an effort at branding,” she said. “I don’t use it myself. It excludes a lot of people living in gray areas. Maybe you are just a man who likes to wear skirts.”

Hard edge or fragile, queer-branded fashion remains a tough sell. Mr. LaForge said he found no takers for his one-off designs at Bergdorf Goodman, where they were briefly showcased. He now sells primarily through Patricia Field and to private clients.

Ms. Fleury’s customers frequently puzzle over just how to wear her designs, which she sells mostly to artists, dancers and other performers.

“I make the clothes,” she likes to tell them. “You figure out what to do with them.”