For the first time over a half century, more people in the United States are dying at home than in hospitals, a remarkable turnabout in Americans’ view of a so-called “good death.”

In 2017, 29.8 percent of deaths by natural causes occurred in hospitals, and 30.7 percent at home, researchers reported on Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The gap may be small, but it had been narrowing for years, and the researchers believe dying at home will continue to become more common.

The last time Americans died at home at the current rate was the middle of the last century, according Dr. Haider J. Warraich, a cardiologist at the Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System and a co-author of the new research.

In Boston in 1912, about two-thirds of residents died at home, he said. By the 1950s, the majority of Americans died in hospitals, and by the 1970s, at least two-thirds did.

Americans have long said that they prefer to die at home, not in an institutional setting. Many are horrified by the prospect of expiring under florescent lights, hooked to ventilators, feeding tubes and other devices that only prolong the inevitable.

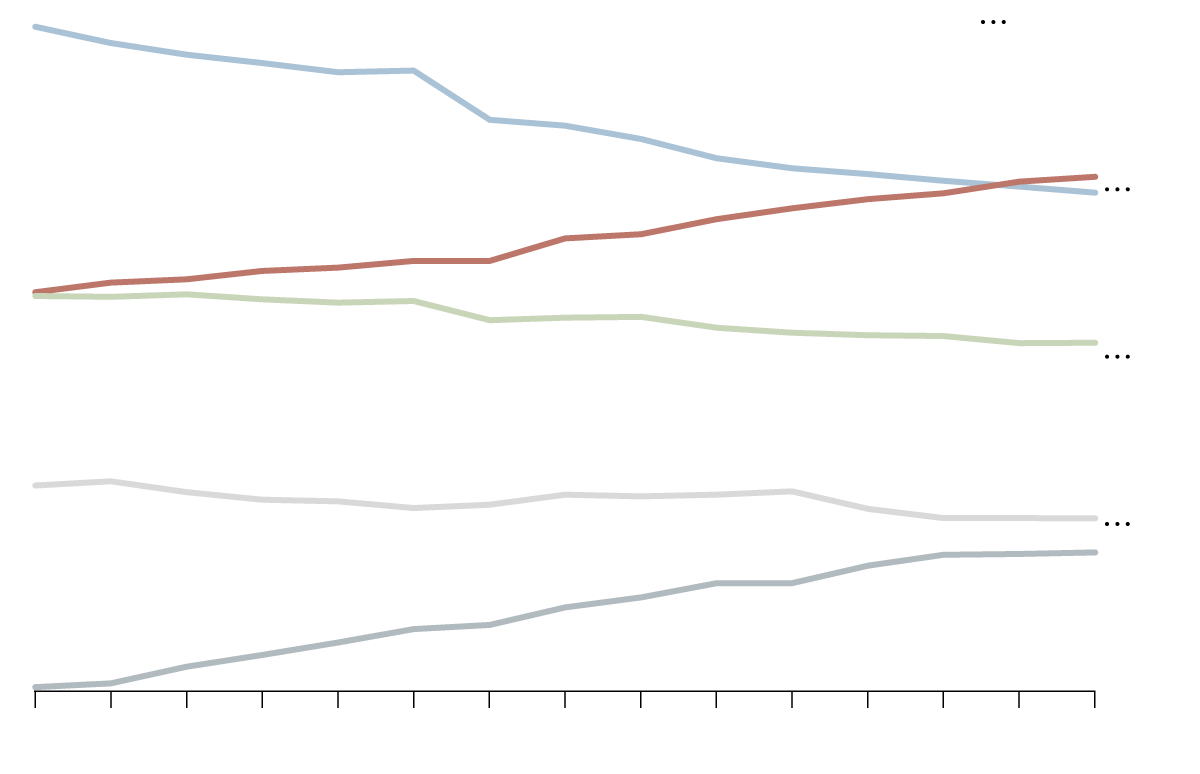

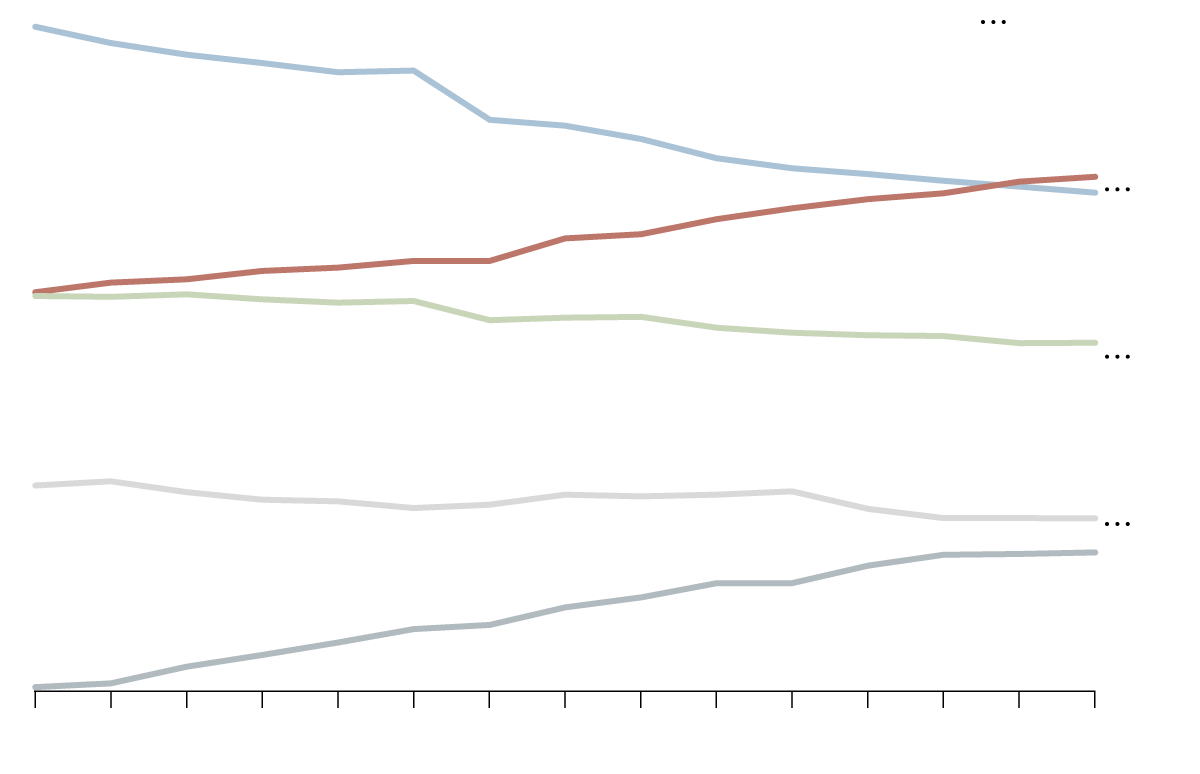

Home Deaths

The portion of people dying in their homes has surpassed those dying in hospitals.

40% of deaths

40% of deaths

Nursing facility

Nursing facility

Hospice facility

Hospice facility

40% of deaths

40% of deaths

Nursing facility

Nursing facility

Hospice facility

Hospice facility

And hospice care, usually delivered at home, is more available than ever before. Some 1.49 million Medicare beneficiaries received hospice care in 2017, a 4.5 percent increase from 2016, according to the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization.

“There has been a kind of cultural shift that has romanticized dying at home and made it the only way to die,” said Carol Levine, an ethicist at the United Hospital Fund in New York.

At the same time, hospitals have long had financial incentives not to keep Medicare patients for long periods, noted Dr. Diane Meier, a professor of geriatrics and palliative medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York.

Typically, Medicare pays hospitals per diagnosis per patient, not for the number of days a patient is in the hospital. Administrators “don’t want it to go on for a long time,” Dr. Meier said.

“We send very very sick, complicated patients home under the care of family members who are not trained professionals,” she added.

Many terminally ill patients wind up in the care of family members who may be wholly unprepared for the task.

“We are, perhaps appropriately, shifting the site of care to where patients and families say they want to be,” said Dr. Sean Morrison, chair of geriatrics and palliative medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York.

But, he added, “We have put a tremendous burden on families in the type of care they have to provide and the type they have to pay for.”

Margaret Peterson, 58, a fellow at the Chicago Center for Family Health, cared for her terminally ill husband, Dwight, at home for four long years.

A paraplegic adamant that he wanted to die at home, he was discharged from a hospital in 2012 and enrolled in hospice care, because he was not expected to survive long. But he confounded expectations, living for four years.

Ms. Peterson was his caregiver, along with a home health aide once a week and nurses from a hospice. The burden was crushing, she recalled, and her husband’s suffering in the last few days seemed needless.

“It just went on and on and on,” she said. “The model of care wasn’t designed to give me any respite. It was absolutely exhausting.”

When he had a terrible bedsore on his foot that needed care, Ms. Peterson knew she did not have the training to help him. A friend, a vascular surgeon, offered to come several times a week to treat the wound.

“It was wonderful, but it’s like these GoFundMe things,” she said. “We should not have to resort to a doctor to do us an enormous favor.”

For the last four days of his life, Mr. Peterson was in excruciating pain. Still, he did not want to return to a hospital, because he did not want to die there.

“He had way, way more pain than he needed to have,” Ms. Peterson said. Her husband died on March 6, 2016, from deterioration and infection of his hips and pelvis, a consequence of his paraplegia.

“There is a kind of fantasy where if you make all the right choices, you get this beautiful and peaceful death,” she added. “But you can do everything right and still have an unpredictable and tragic experience.”

Part of the problem is that often hospice care remains relatively limited. Many patients now dying at home need substantial care, said Dr. Warraich.

“Hospice is asked to do a big lift,” he said. “They get a fixed payment, a daily rate for patients, so they cannot offer many services. They are asked to be very effective but on a razor-thin budget.”

Families often are trapped by gaps in the system, said Dr. Meier.

“I don’t think families or caregivers understand what it’s like to die at home,” she said. “They will need to understand how to manage symptoms, like pain or shortness of breath or confusion. They are on-call 24/7 and have to be alert to changes at all times. They don’t get to go home after an eight-hour shift.”

“Even with hospice care, families are the front-line caregivers,” she added. “Ninety nine minutes out of 100 the family is on its own.”