Imagine if Kodak had answered the threat of digital photography by pivoting from film to outdoor grills.

Imagine if Blockbuster had taken on the challenge from Netflix by shifting from DVDs to fast food.

Imagine if men’s magazines stared down the post-#MeToo manpocalypse by disowning men.

Maybe the last one isn’t so hypothetical?

At a time when calls are growing for the Oscars, Tonys and Emmys to follow the Grammys and the MTV Video Music Awards in erasing gendered categories, and to do away with gender-specific magazines, bro bibles like GQ, Esquire and Playboy seem poised to do a backpedal of Michael Jackson moonwalk proportions from the formula that kept them perched at the publishing pinnacle for a half-century.

Namely, being a print version of your father, offering up bourbon-breathed tutorials on the arts of tie knotting, fly casting, and skirt chasing.

In the gender tornado of 2019, men’s magazines, it seems, are canceling themselves. (The internet’s assault on glossy print isn’t helping either.)

“How do you make a so-called men’s magazine in the thick of what has justifiably become the Shut Up and Listen moment?” wrote Will Welch, the editor of GQ, in a cri de coeur introduction to this month’s “New Masculinity” issue. “One way we’ve addressed it,” he continued, “is by making a magazine that isn’t really trying to be exclusively for or about men at all.

So gender fluid it’s soggy, the 128-page issue might well have been themed “No Masculinity,” with its androgynous cover image of Pharrell Williams looking like an inverted tulip in a floor-length yellow Moncler Pierpaolo Piccioli coat, followed by ruminations on the “weaponized” male body by Thomas Page McBee, a transgender writer and boxer; a defense of makeup for men by EJ Johnson, Magic Johnson’s son whose fashion tastes run toward fur shawls and diamond chokers; and a debunking of the power of testosterone itself by Katrina Karkazis, a cultural anthropologist and author.

Such untraditional content is a survival strategy for glossies with a Y chromosome tilt in this homo novus era, where every reference to masculinity wears an implied “toxic” like a hair shirt.

Even Playboy, mired in identity crisis since dial-up modems, is suddenly woke.

The magazine has rechristened its Bunnies as “brand ambassadors,” and even embarked on a short-lived experiment to cut out the nudes. After the death of its founder Hugh Hefner in 2017, Playboy has morphed into an art-book quarterly that ditched its old tee-hee-hee motto, “Entertainment for Men,” for a gender-blinkered “Entertainment for All.”

It’s an open question whether the men who now turn to Pornhub and its ilk for the kind of “entertainment” that Playboy built an empire on even noticed.

Even so, the magazine, which long held up Hef, with his phallic-symbol pipe and star-studded skin romps at the Playboy Mansion, as the epitome of American straight male aspiration, is turning the brand’s hyper-male, hyper-hetero legacy on its head.

The magazine’s new leadership team consists of a gay man (the executive editor Shane Singh) and two women (the creative director Erica Loewy and Anna Wilson, who is in charge of photography and multimedia), all millennials.

Recent feature articles include profiles of Andrea Drummer, a female African-American chef who runs a cannabis-centric restaurant in Los Angeles, and King Princess, a genderqueer pop singer who is as a symbol of self-acceptance to young L.G.B.T.Q. fans.

For a cover image this summer, the team commissioned the fine-art photographer Ed Freeman (a rare man who still shoots for Playboy, though he is gay) for an arty underwater shot featuring three featuring female activists for causes like ocean conservation and H.I.V. awareness.

“The water,” Mr. Singh explained to Jessica Bennett of The New York Times for an article in August, “is meant to represent gender and sexual fluidity.”

Change is also afoot at Esquire, the tweediest of the men’s titles, which for decades carried a whiff of dad’s old cedar chest full of full pocketknives and Mickey Mantle baseball cards.

This past June, the magazine installed its second editor, Michael Sebastian, in three years. Mr. Sebastian, 39, made his name as Esquire’s digital director, where he oversaw a significant rise in traffic to the site, according to Hearst.

His appointment as editor prompted industry speculation that he was going to go “full Cosmo,” chasing Instagram-friendly content and trending topics on Twitter just like Cosmopolitan, Esquire’s sister publication at Hearst that has lately been pursuing data as hotly as it long proselytized multiple orgasms.

The move seemed symbolic. Mr. Sebastian replaced Jay Fielden, a dapper Texan given to Hemingway and Cifonelli suits, who had departed weeks before, citing the lure of new (and unspecified) possibilities. Mr. Fielden had vowed to revive the “literary charisma” of the magazine of Fitzgerald and Dos Passos. He may have fit the image of the “Esquire man” too well for the times.

In one of his first interviews after he got the job, Mr. Sebastian took a swipe at the publishing patriarchy, telling The Wall Street Journal that he wanted to get away from the idea “that both the Esquire reader and writer is a middle-age white guy who likes brown liquor and brown leather.”

In fairness to Mr. Fielden, he said pretty much the same thing years ago, before Harvey Weinstein and his ilk sent half the population to the penalty box. “There’s no cigar smoke wafting through the pages,” he said to The New York Times in 2017, “and the obligatory three B’s are gone, too — brown liquor, boxing and bullfighting.”

As the same article reported, Mr. Fielden had won the job in part because he courted more male readers to the traditionally feminine Town & Country, the Hearst title he headed before Esquire.

At Esquire, he vowed to lure more female readers and ditched boys’ club staples like the print version of the “Women We Love” issue.

Apparently, it was not enough. Could anything be? Perhaps not, as manhood itself is being interrogated, scrutinized and radically revised.

The very idea of a men’s magazine now sounds “as hopelessly passé as a private gentlemen’s club,” according to a recent article, “The End of Men’s Magazines,” in City Journal, which is not exactly a progressive organ (the magazine is published by the Manhattan Institute, a free-market think tank).

Maybe. Or maybe not.

Details is done. Maxim has evolved its identity from a frat-house must-read to a cosmopolitan lifestyle magazine, an about-face that began under a female editor and fashion veteran, Kate Lanphear, who departed in 2015.

But Esquire has already survived the Great Depression, World War II, disco, yuppies and the dot-com bust. It’s still here.

And plenty of readers are still here, too, even in a brutal publishing climate that has forced august women’s titles like Glamour, Seventeen, Self, and Redbook to retreat from print for the web.

Despite a plunge in newsstand sales that has plagued the whole industry, Esquire still had an estimated total average circulation of 709,000 for the first six months of this year, according to the Alliance for Audited Media; the figure accounts for both print and digital subscriptions as well as single-copy sales.

GQ, too, is a long, long way from life support, with a figure of 934,000 for the same period, according to the alliance.

Times change, sometimes violently. But recent history is full of apparent anachronisms (gas guzzlers, Birkenstocks, Donald Trump) that managed an unlikely second act. And men’s magazines have proven pretty adept at sniffing out the shifts in culture, both trivial and seismic, over the decades — which is one reason they have been around for decades.

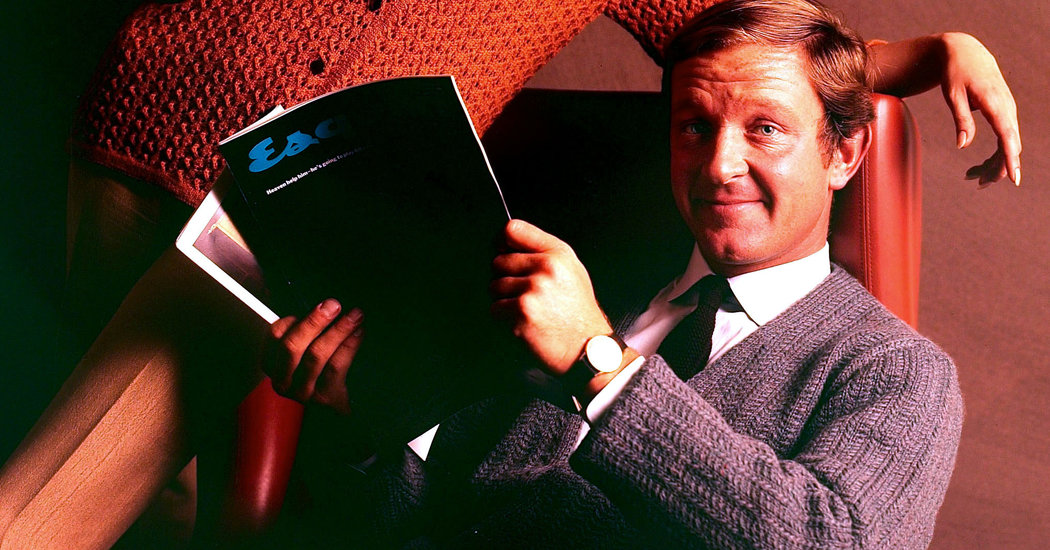

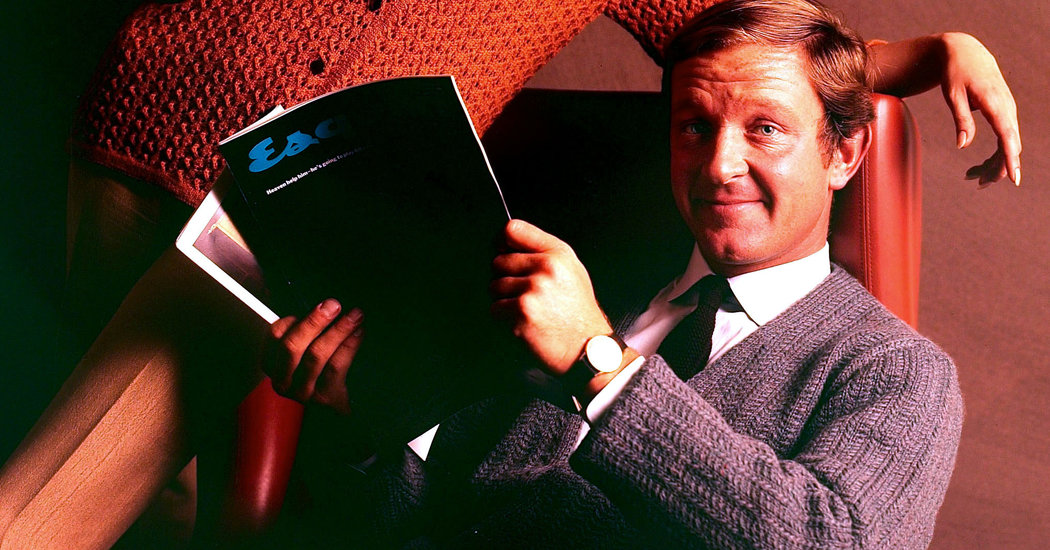

Esquire may have swaggered into the 1960s as the Don Draper of magazines, but as the old order began to crumble thanks to Betty Friedan, the Black Panthers and many others, the magazine’s editor, Harold Hayes, quickly detoured into a flower-power-era version of woke.

He commissioned Susan Sontag’s dispatch from Hanoi at the height of the Vietnam War, and James Baldwin’s ruminations on race in America after the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Even Playboy opened its pages to thought-provoking interviews with Eldridge Cleaver, Malcolm X and Fidel Castro while sprinkling in at least a few pictorials featuring Playmates of color.

Yes, that was a different time. We’ve come a long way from Gloria Steinem decrying “The Moral Disarmament of Betty Coed” thanks to the Pill in Esquire in 1962, to Hannah Gadsby, a lesbian comedian, taking aim at “hypermasculine man-babies” in GQ’s “New Masculinity” issue.

Haven’t we?